A proposal that critiques urban greenwashing by a team of Australian landscape architects has been recognized in an international ideas competition. The LA+ Interruption competition run by US-based interdisciplinary journal LA+ asked entrants to consider how design could be used to “challenge the status quo, to interrupt the jargon, to disrupt and redirect ecological and socio-economic lows.”

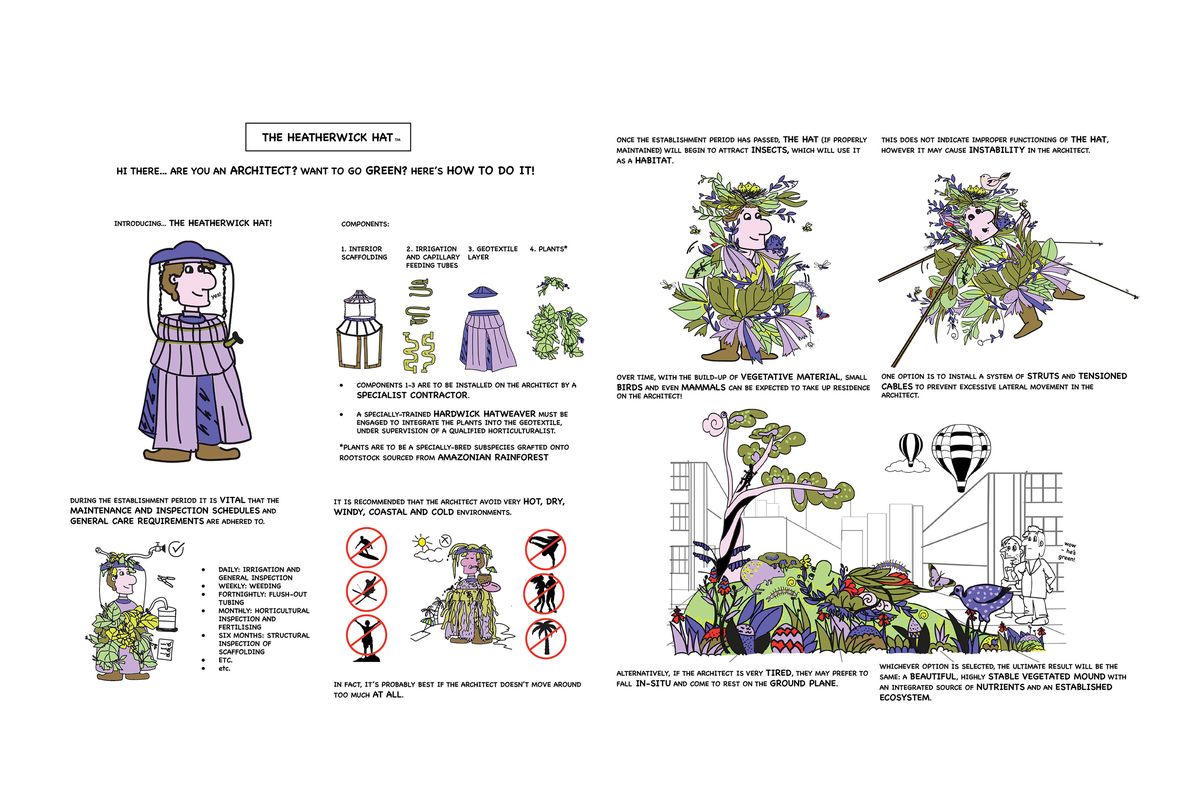

The Melbourne and Launceston-based team of Anna Feldman, Gagani Warnakulasooriya and Danyelle Bailey received the “Editor’s Choice” award for their satirical proposal, The Heatherwick Hat.

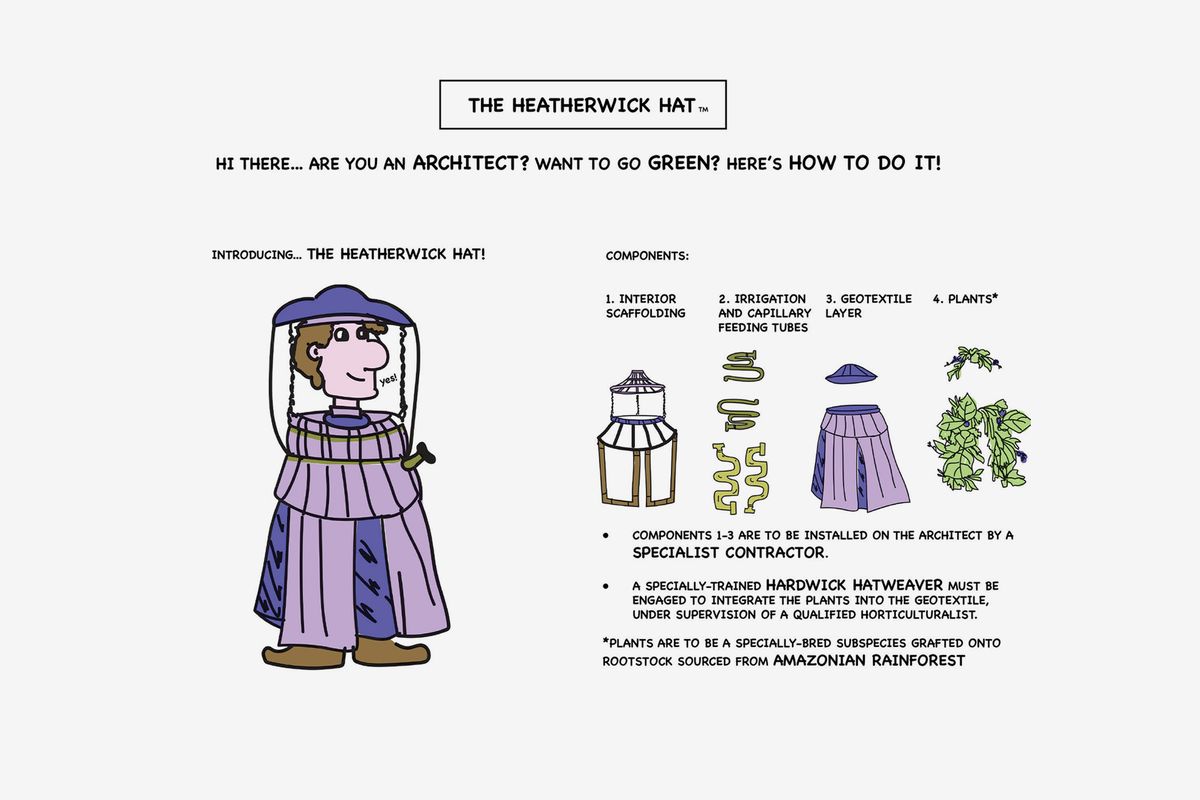

“All over the world architects are asking themselves, “How can I make this project more ‘green’? And all too often the answer is to put some plants on it, without a nuanced consideration of whether a green wall or roof is really a suitable (and environmentally friendly) option in the circumstances,” the proposal reads.

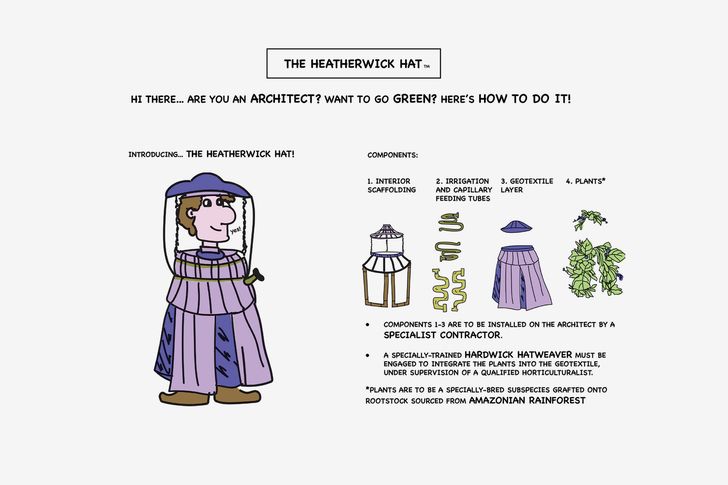

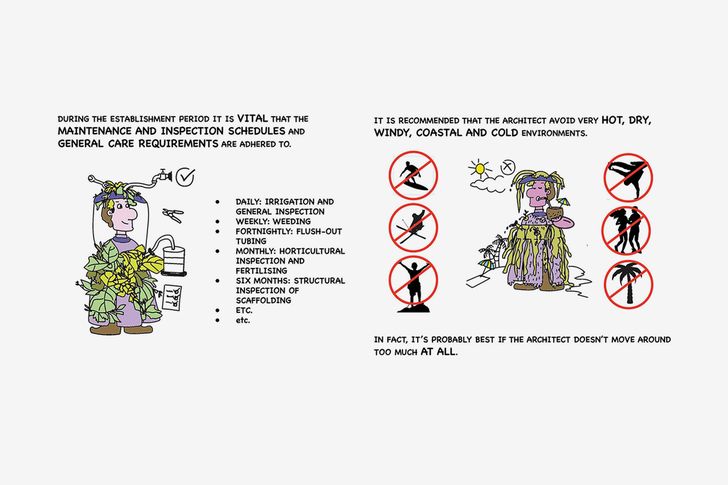

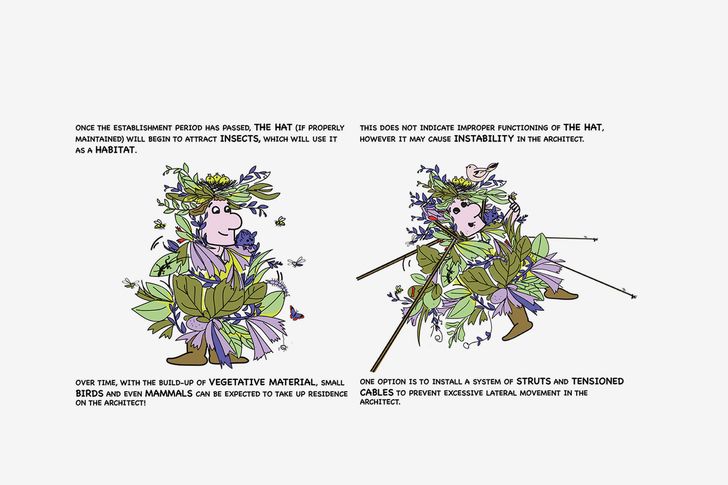

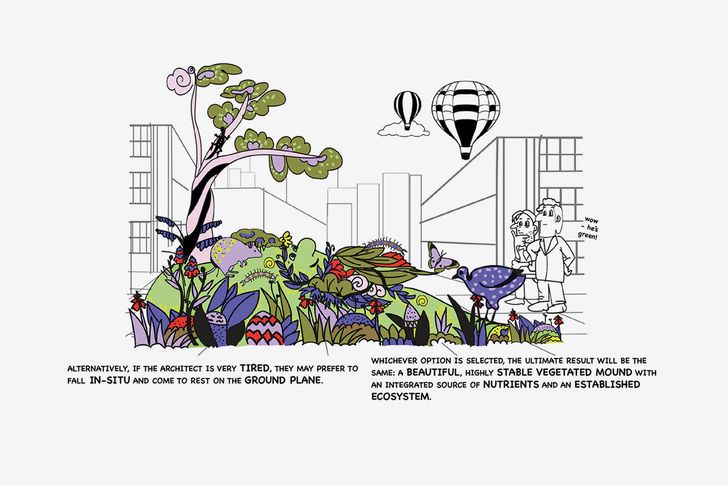

“The Heatherwick Hat is a structure designed to support the growth of plants over the human body. Rather than installing plants on structures, architects can simply don The Hat.”

Landscape Australia spoke to the design team about the issues that drove their design concept, the relationship between plants and buildings, and how we can create more beneficial and sustainable greenery in our urban environments.

The Heatherwick Hat by Anna Feldman, Gagani Warnakulasooriya and Danyelle Bailey

Emily Wong: What was the thinking behind the development of The Heatherwick Hat? You’ve taken quite a different approach to the other entries in the competition, in particular to those that received the major awards.

Anna Feldman: Often when it comes to these ideas competitions we all try to save the world, we tend to go as big as we can and think of what are the problems we want to solve, rather than what are the problems that we have the tools and knowledge to solve. The idea behind our proposal was to poke a bit of fun at architects, landscape architects and other built environment professions about how we think so big and try to do so much when the tools that we have are really well suited to more concrete and even small-scale solutions.

Danyelle Bailey: We see humour as a way to encourage people to reflect on their own practice a little bit. We’re not forcing anyone to think anything, but inviting them to laugh and then go, “oh actually have I come across this before?” The site of the proposal is the human being – and we’re poking fun at some of the professional outcomes of design, rather than particular people themselves.

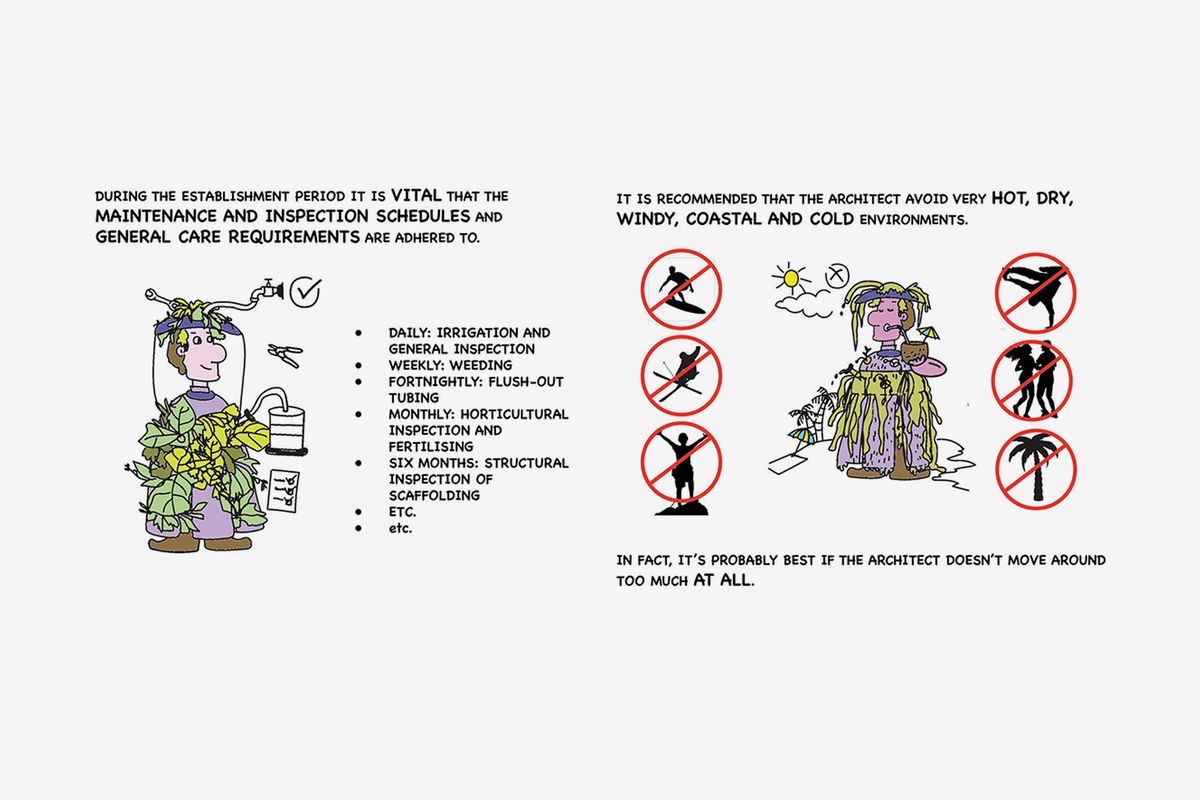

The Heatherwick Hat by Anna Feldman, Gagani Warnakulasooriya and Danyelle Bailey

Your proposal responds to the issue of superficial greening. What are the problems you see with this – and are there specific projects you had in mind?

DB: There’s the obvious link back to [UK-based architecture practice] Heatherwick Studio, which certainly does produce some amazing stuff, but also creates designs like their 1000 Trees project in Shanghai. Here, the studio has put forward an idea of greenery which looks incredibly grand. It seems to be providing solutions where there was little existing greenery – in the sky. But is this planting actually contributing to the wider ecology? Is the soil in the design appropriate? You’re shifting soil from one site to another and the links which encourage a healthy and thriving ecology are missing. You’re not getting mycelium in the soil, you’re not considering how challenging the conditions will be by [having plants] placed above the ground plane, or the resources it takes to do so. The planting design, in this sense, is arbitrary. It’s simply putting a bunch of green things in planters without deeper reflection.

AF: Heatherwick Studio often seems to approach [planting design] in an infrastructural way, in a way that most likely requires heavy input of machinery and maintenance and lots of stuff to get it started and keep it going, especially in the challenging sites. The whole green plants over buildings thing is really [suited to] Singapore, or places where there’s a lot of humidity in the air and the climate is fairly consistent – conditions quite unlike Melbourne, for instance. The issue we wanted to highlight in our proposal is that plants on buildings often seem to be seen as a panacea, rather than as a highly site-specific kind of intervention dependent on a very careful consideration of conditions. A local example that we think gets it right is Parliament of Victoria Member’s Annexe [Peter Elliott Architecture with TCL]. The plant species are appropriate to the climate and the vegetation is contributing in multiple ways to the outcome, rather than just being decorative.

Architectural renders often don’t help – so many images of enormous, thriving green trees abstracted from the realities of site conditions and plant growth.

AF: The brutalist-style Henty House in Launceston where I had an office was originally designed as a sort of ziggurat with all this cascading vegetation and stuff. But the plants – I don’t know if they ever went in, but they’re certainly not there now – and I haven’t seen any images where they were ever even installed.

DB: [Architectural renders] are great at selling an idea. [They often depict] a very lush, very homogenised, very “complete” idea of a landscape. You understand the lifetime of a building, when it’s complete, and thereby habitable. It’s much less obvious with a landscape when (if ever) it’s complete. But that notion’s harder to sell. I do think that architectural renders have been around long enough now that we’re becoming [more] critical of them and looking beyond the idealized render.

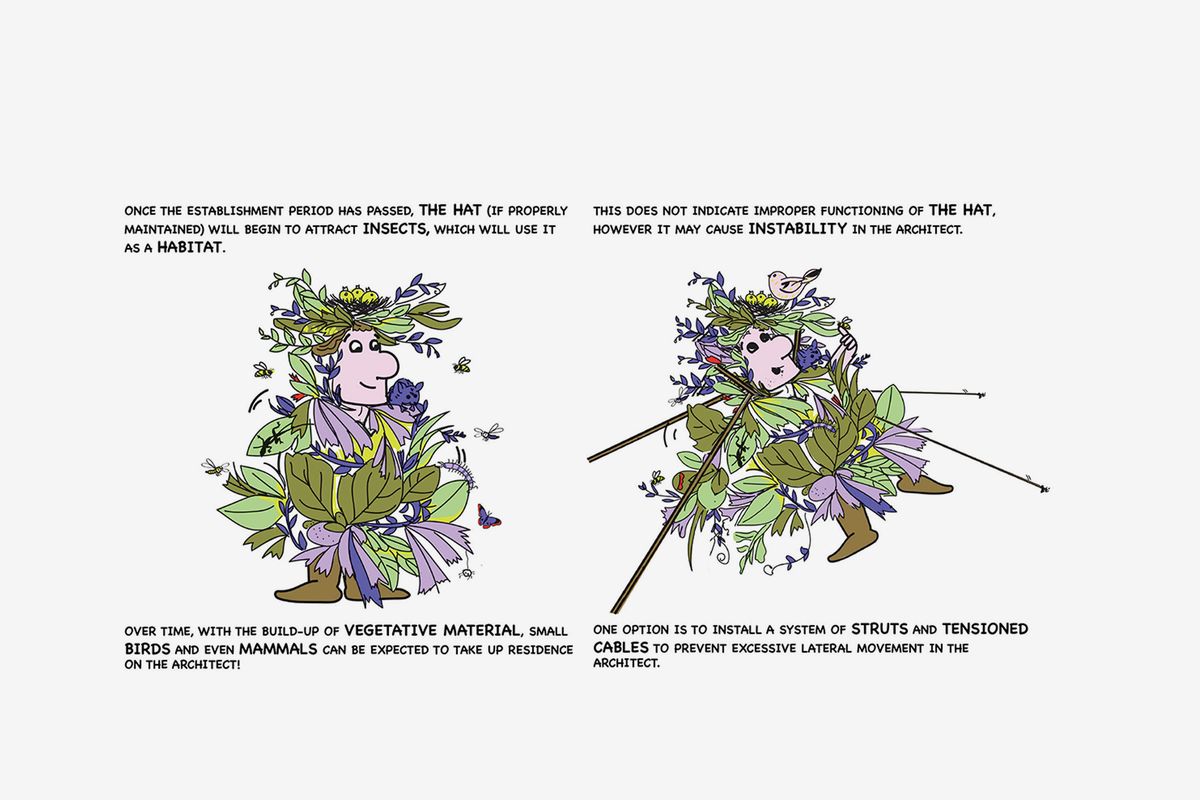

The Heatherwick Hat by Anna Feldman, Gagani Warnakulasooriya and Danyelle Bailey

What advice would you give to architects who want to incorporate more “green” into their projects?

AF: First of all, think sensitively about how you site your planting. If you decide you want a green wall, ask why you want the green wall. Is it just because you think it would be an easy way to soften the look of a building, to make it seem greener and more environmentally friendly? Or is it because it works with the intent of the building in other ways? Are the conditions on that facade conducive and supportive of plant growth – or are you actually just pushing sh*t uphill trying to get it to work there? There’s a difference between a green wall that gets nice, filtered light and a bit of moisture on a day-to-day basis, and one that’s just getting pummelled by the western sun every day.

Gagani Warnakulasooriya: My suggestion would be to think about specific species more carefully and what kind of maintenance they might require. Talk to professionals from related fields like horticulturalists and gardeners. You might already have a set of plans that [includes] a green wall but think about how these need to be adjusted from site to site. Planting design should be a [collaborative] activity, where a range of professions have their perspectives and their respective input.

DB: Plants can be object or ornament, if that’s their role in that particular project. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing, but I think [there is the problem of] opportunistic planting, where the designer thinks, “well, we’ve designed what we’ve set out to design, now where can we place our plants?” That kind of approach is very unlikely to produce a [sustainable] approach to greening that provides actual benefit – whether the ambition is to increase biodiversity, provide cooling, or enhance the building’s aesthetic. There needs to be an understanding at the start of a project that if you’re going to introduce greenery and have it contribute to the ecology or the biodiversity of the area, it needs to be discussed across disciplines at the project’s initial stages. Professionals, like horticulturalists for instance, have expert knowledge, so refer to them, and you’ll ensure some really good outcomes – collaboration, in these cases, is key.

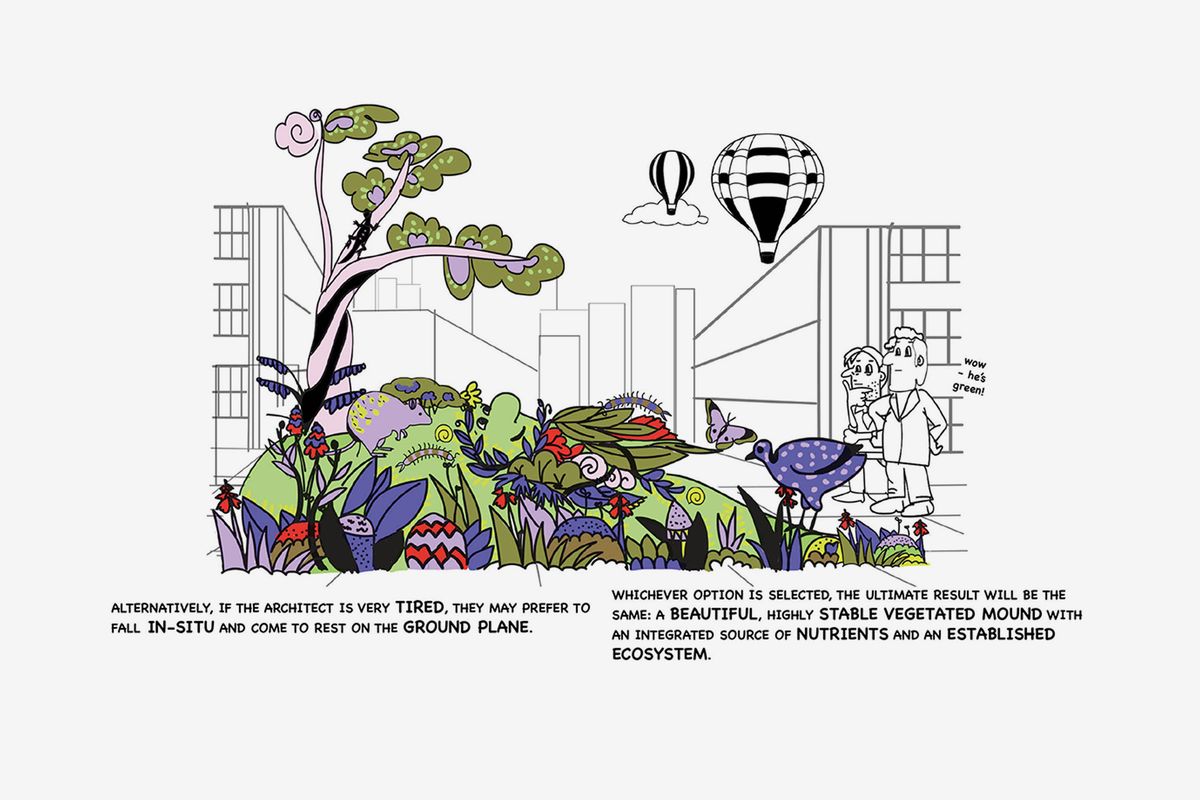

The Heatherwick Hat by Anna Feldman, Gagani Warnakulasooriya and Danyelle Bailey

What’s your vision for the future of greenery in cities?

AF: Definitely some gardens in the sky, but more importantly lots of publicly accessible space carved out for people and plants at ground level. Policy isn’t going far enough in this area [at the moment], so it’s something everyone in the built environment professions should work together to push for.

DB: Personally, I’m very critical of the idea of flattening an area of land and replanting it. Many sites harbour existing vegetation, and such spaces often have an amazing “wild” quality to them. [We should] put more emphasis on retaining existing plants and nurturing the existing ecology of a site, building on the beauty that is already there. And then planting trees that are going to be able to survive in the future – I think that’s the biggest thing. The climate is going to change massively over the next 50 years. We need to make sure that our plant lists are really keyed towards species that can thrive in our sites for quite a long time.

GW: My hope is that in the future, green space, rooftop gardens and even vertical gardens in the city aren’t a private luxury but instead abundant – in every street and underutilised space – and accessible to everyone. That we won’t be in the situation of googling for the nearest green space, only to find out that it’s private.