A long time ago, there was a limestone hill wedged between the Derbal Yaragan – a slow, serpentine river – and the vast ocean. Its western face was covered with coastal heath while a tuart forest, watered from a small seep, grew in the protected hollow at its base. The Whadjuk people of Noongar Country referred to the limestone hill and coastline as Booyeembara, meaning “of limestone hills.” The limestone hill was one of seven hills known as the Seven Sisters of Walyalup (“place of the eagle”), after an important Whadjuk dreaming story.1

Booyeembara Park is located on the site of that ancient limestone hill in Fremantle, Western Australia. The park has been shaped by the tensions between different value systems connected to Indigenous culture, colonization, laws and governance, landscape architecture and community. A hierarchy of value currencies, ranging from the Whadjuk people living in relative harmony with the landscape to the behaviours and attitudes of colonizers pursuing extractive quarrying, land management and ecological control, have all had a hand in shaping the park into what it is today.

A photo taken in 2001, showing the varied topography of the site and its plantngs.

Image: Ecoscape

Designed in the late 1990s, with construction commencing in 2000, Booyeembara Park is now more than 20 years old. Over this period the park has received acclaim and suffered neglect, and it is now re-emerging as an important green space within the increasingly densified suburb of Fremantle. Its name has been affectionately shortened by the locals to “Boo Park.”

After colonization, from the mid-1800s up until the 1960s, Booyeembara was quarried for limestone to construct buildings and roads throughout the locality of Fremantle. Sadly, only one of the Seven Sisters hills remains today.2

Once its value as a quarry was exhausted, the hill became a landfill site for all things discarded by the people of Fremantle. It filled with non-organic hazards, finally becoming a wasteland of rubble and weeds. In the intervening years, the site became a place where children explored and locals walked their dogs. These adventures helped begin the transformation of the abandoned site into a familiar and valued part of the neighbourhood.

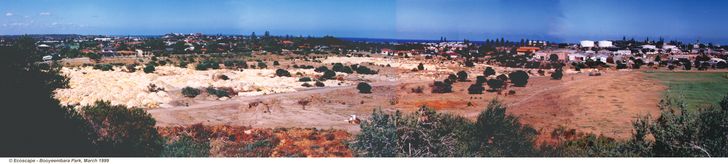

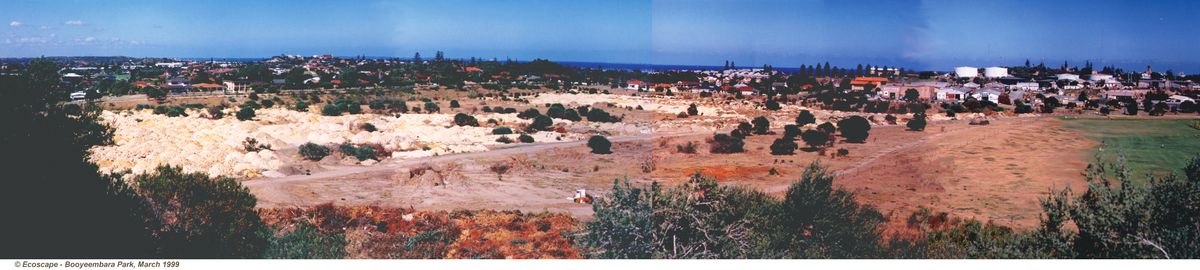

A photo taken of the Booyeembara Park site in March 1999, prior to construction.

Image: Ecoscape

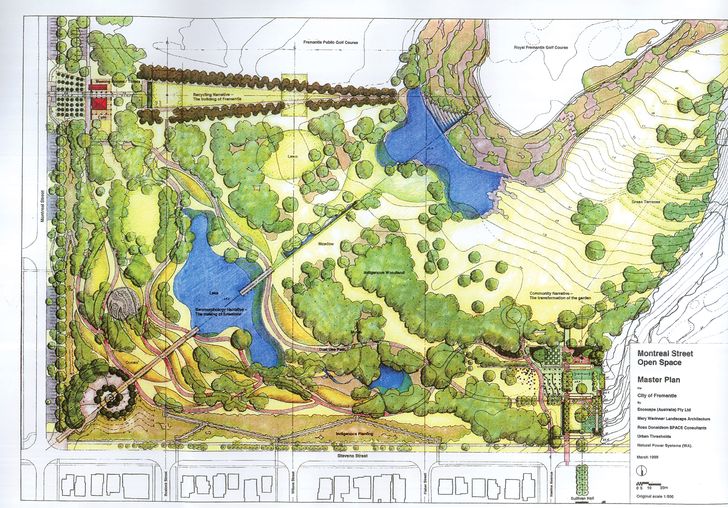

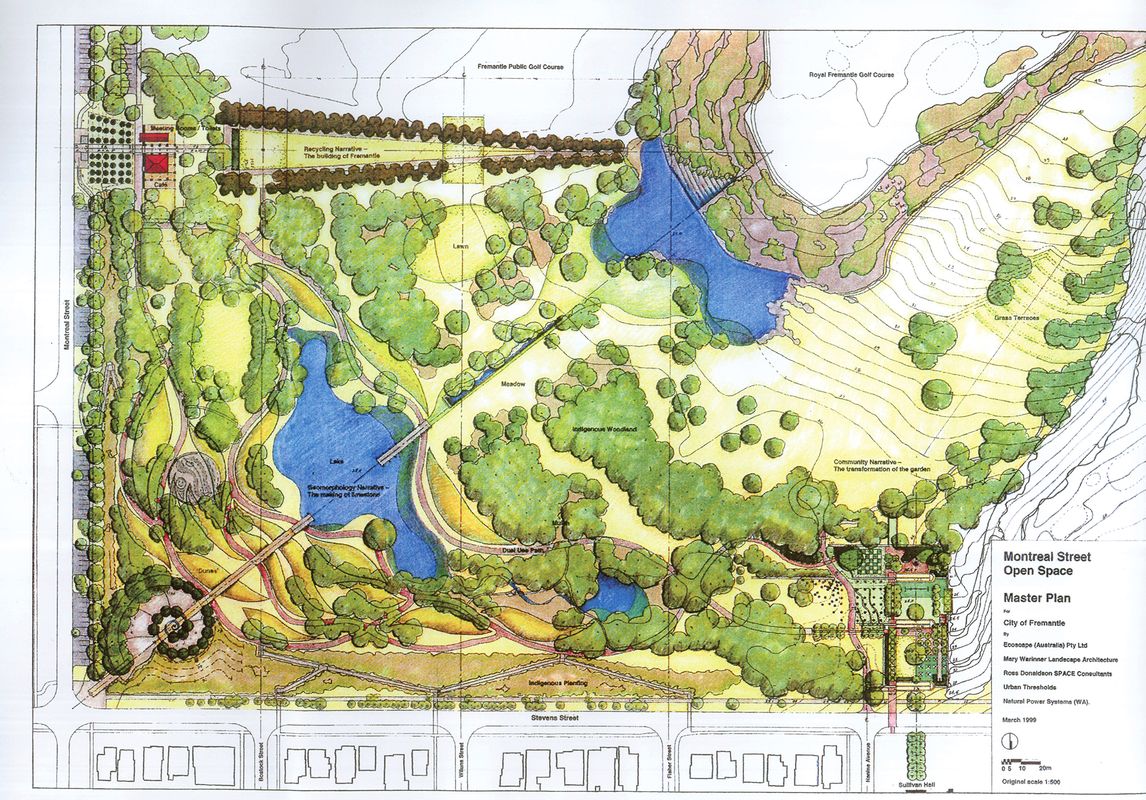

The 1999 masterplan for Booyeembara Park organizes the site along three axes based on Fremantle’s landform, environment and culture.

Image: Ecoscape

In 1993, the City of Fremantle called for community submissions to determine how the site could be redeveloped. The overwhelming message from the community was to sanctify its informal recreational use by creating a park. A masterplan and detailed designs for the park were developed from 1997 to 1999, led by landscape architects Ecoscape with Mary Warinner Landscape Architecture, Space Consultants, Urban Thresholds and Natural Power Systems, in close collaboration with local elders, community representatives and the City of Fremantle.

David Kaesehagen, founder and director of Ecoscape, described the process as “forward thinking, combining contemporary ecological thinking and community participation to create the future lung of Fremantle.” While the scheme imposed a top-down order of a “master” plan by structuring the landscape along three axes that can only be fully understood from a bird’s-eye view, each axis is assigned a narrative “based on Fremantle’s landform, environment and culture,”3 cohesively connecting the community’s ideas to the site.

The “Geomorphological Axis,” representing the local geomorphology and the formation of limestone, runs from the intersection of Montreal and Stevens streets to the remnant limestone hill. An artificial billabong formed from a freshwater soak at the base of the hill also sits on the axis. Running along the northern boundary of the site and aligning with the Fremantle settlement and the limestone hill is the “Recycling Axis.” This axis attempts to join the dots between the historical quarry and the relationship between the extractive exploitation of cultural landscapes and the buildings of the city. Finally, the “Community Axis” expresses the relationship between the community and nature. It explores the concept of nature through three terraced gardens intended to represent the past, present and future. The future garden fully embraces the indigenous landscape, with native plants replacing exotic ones.

The 1999 masterplan for Booyeembara Park organizes the site along three axes based on Fremantle’s landform, environment and culture.

Image: Ecoscape

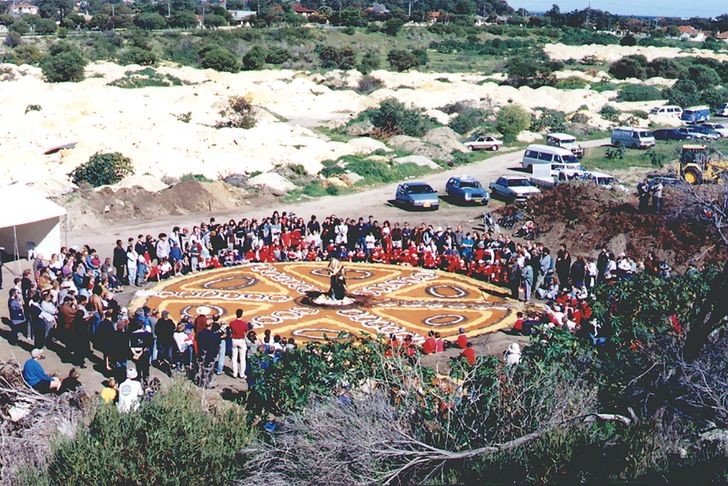

Noongar elder Marie Thorne conducted a healing ceremony at the park in 2000, prior to construction works commencing.

Image: Ecoscape

In 2000, a healing ceremony was held at the base of the hill by local elder Marie Thorne to celebrate the restoration of the landscape and the spirit of the place.

Six years later, with the implementation of the masterplan ongoing, the park was awarded the 2006 WA state award by the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) in recognition of its “sound ecological principles that are informed by cultural awareness and the rich history of Fremantle.” Of particular note, the jury said, was the involvement of the community in developing the park.

In that same year, to celebrate 40 years of AILA, the park was recognized as one of just 40 Landscapes of National Significance, an honour that recognized “significant designed sites and urban spaces that have either retained the integrity of the original design and/or been managed with the clear intention to evolve the design towards defined and articulated stewardship objectives.” It still holds this title, along with other nationally treasured and carefully managed landscapes in the state such as Kings Park and Botanic Garden and the Tree Top Walk in the Walpole-Nornalup National Park.

But this recognition belies the unfortunate truth that development of the park was abruptly halted in 2009, when asbestos was discovered in the waste material dumped during its time as a landfill site. Only the Geomorphological Axis and part of the Recycling Axis were ever completed.

Vast areas of the park, including a community-initiated and -built amphitheatre, were fenced off. A change in leadership diminished the City of Fremantle’s motivation to finish the park and, despite intensive lobbying by David Kaesehagen, the new management struggled to understand the environmental and cultural significance of the design and the park. While the completed sections have been relatively well maintained, a shift in local government agendas and budgets, and operational constraints, have seen fenced-off areas fall further into neglect. The council itself recognizes that “since 2006, numerous minor works have occurred within the site that, when considered in a site wide context, detract from [the Landscapes of National Significance] accolade and currently the site is failing to meet expectations of community and council.”4

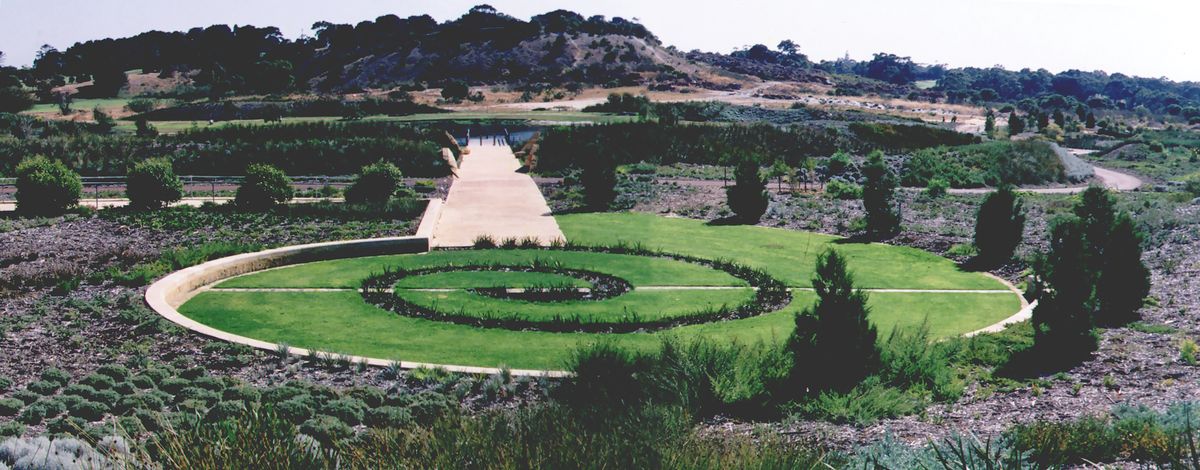

An artificial billabong lies along the line of the Geomorphological Axis, the only fully completed axis of the original design. Photo taken in 2006.

Image: Ecoscape

Despite this, the drive and commitment of the local community has remained constant. The decades of lost time during which the park remained incomplete have given the community an opportunity to adopt the park and continue to shape the space into its own. Stephanie Jennings, a long-time Boo Park community advocate, claims that community members “hold and continue to hold the story of the park.”

The olive grove along the Recycling Axis has evolved into a place of feasting and gathering. Each year, the White Gum Valley Community Orchard invites locals to harvest the olives. Afterwards, the community shares the harvest at a long-table feast, with entertainment by local Sicilian musicians.

In the eastern part of the park, earmarked for the Community Axis, a group of locals has constructed a series of mountain bike trails and pump tracks for the local kids to enjoy. These were recently formalized by the City of Fremantle, with the assistance of the Booyeembara Park Mountain Bike Trail Working Group.

Community groups, including Friends of Boo Park, participate in caring for the park, holding regular planting and weeding days.

Image: Stephanie Jennings

An annual olive-harvesting lunch is held by the White Gum Valley Community Orchard within the Recycling Axis’s now-established olive grove.

Image: Stephanie Jennings

Similarly, members of the Booyeembara Park Yacht Club race their model boats on the lake. Friends of Boo Park (a 100-strong group) bring the community together with regular events and actively participate in caring for the park, holding weeding and planting days. On the full moon, the Reconciliation Circle is the venue for a community drumming circle and dreaming meditation event.

A recent funding boost by the state government has enabled the City of Fremantle to undertake a masterplan review. It defines future projects to revitalize the park, including a new community centre. This coincides with the finalization of a management plan to deal with the asbestos and other hidden contaminants on site.

At first glance, Booyeembara Park, with its intricate and windy path network, playgrounds, lake, lawn and bushland, may look like any other local park. From its aesthetic appearance and the city’s ad hoc commitment to delivering the original concept, it does not compare favourably to the other Landscapes of National Significance. However, its real value should be measured in the relationships it has helped to develop between the City of Fremantle and the local community. The city had the courage to gift the community a blank canvas in 1999 and, since then, a direct dialogue and flow of ideas has enabled the park to evolve to meet community needs. Perhaps this next phase of its history will see a new wave of younger community members take an interest in the park, seeking to strengthen the community bonds, restore the limestone hill’s sacred life-creation story and further reconcile the park’s colonial history with the Whadjuk people of Noongar country.

1. Debra Hughes-Hallett (ed.), Indigenous History of the Swan and Canning Rivers (Swan River Trust, 2010).

2. Ecoscape (Australia), Mary Warinner Landscape Architecture, Space Consultants, Urban Thresholds and Natural Power Systems, Booyeembara Park Master Plan 1999.

3. Ibid.

4. City of Fremantle, Booyeembara Park Review 2020, mysay.fremantle.wa.gov.au/52995/widgets/285483/documents/174892 (accessed 13 May 2021).

Source

Review

Published online: 7 Oct 2021

Words:

Anna Chauvel

Images:

Ecoscape,

Stephanie Jennings

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2021