Phillip Island, off Victoria’s south-eastern coast, is best known for its natural beauty and environmental values. In particular, it is known for the “Penguin Parade,” where little penguins (formerly known as fairy penguins) parade up Summerland Beach each night returning to their burrows. The Bunurong people’s connection to Millowl (the Bunurong name for Phillip Island) extends back tens of thousands of years. But as with most of Australia, the past 200 years have seen a dramatic change to the island’s natural landscape. Nearly 100 years ago, the first tourists began to visit the island, and it has since grown to become one of the state’s major tourist destinations. Over this period, the work of the local community, state and local government has seen the habitat of the Summerland Peninsula, at the island’s western end, (as well as other parts of Phillip Island) protected from overdevelopment, while being shaped to provide significant economic benefit to the local community.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that the island’s environmental values began to be appreciated for their economic benefits. Local residents began taking tourists by torchlight to see the penguins’ nightly arrival. In 1923, at the opening of Warley Hospital on the island, it was noted that foxes and rabbits were “causing havoc,” with the penguin and mutton bird populations “… doomed, unless the foxes were wholly destroyed.” It was observed at the time that “there was not one place in which the birds and penguins lived that was wholly public property” and that perhaps the whole island might be converted to a “huge sanctuary for the preservation of birds, native bears and other fauna,” that would attract “hundreds of people,” like America’s Yellowstone National Park and reservations in Canada.1

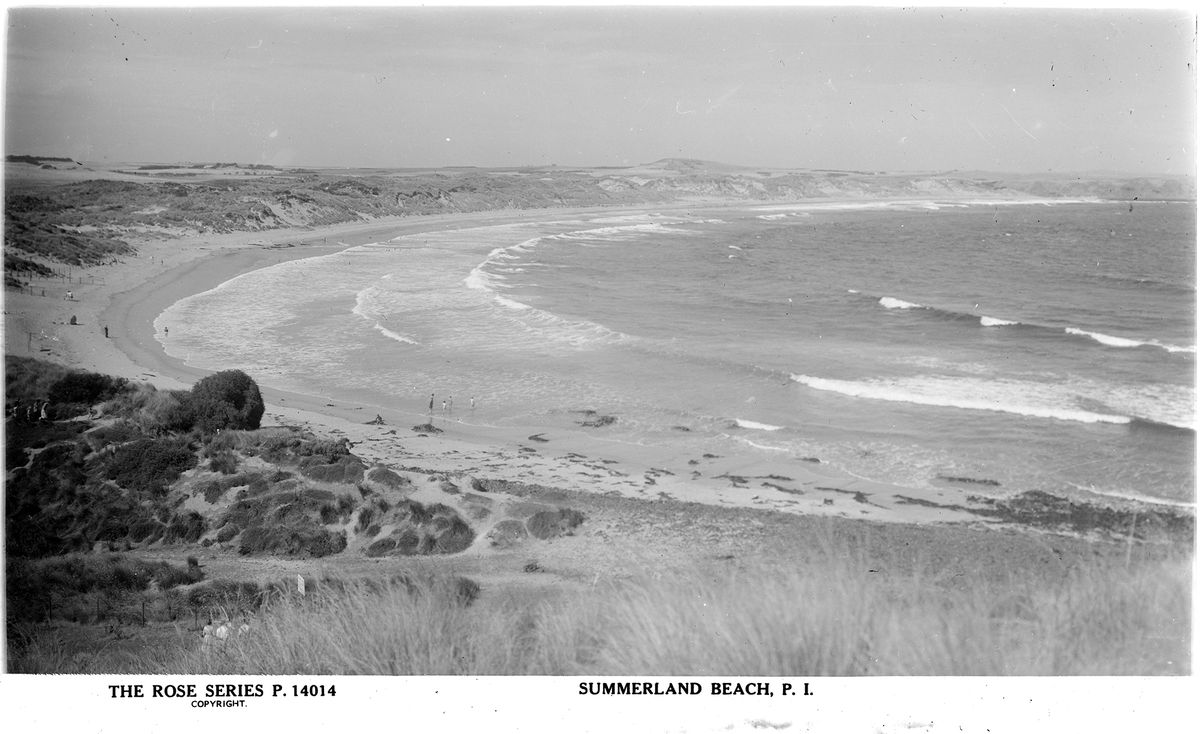

The early days of the Penguin Parade: visitors flock to Summerland Beach to observe the nightly arrival of the little penguins. Image:

Philip Island Nature Parks

A historic postcard from Cowes, the island’s largest township and a popular seaside resort in the region.

Image: State Library of Victoria

In July 1926, a design competition was held to create “A New Township for Phillip Island”2 and by 1927 the “Summerland” project was being advertised, which featured more than 700 lots, a golf course, a commercial strip and “nature’s wonders.”3 An area known even then for its natural beauty had been subdivided. During the 1930s, however, focus in the area shifted to environmental protection. Approximately four hectares of land adjoining the peninsula’s Summerland Beach was donated by the Spencer Jackson family with the aim of protecting the island’s existing penguin habitat.

The worldwide growth of the environmental movement during the 1960s coincided with new initiatives in the area. The Penguin Study Group was established in 1967 and undertook key studies on the area’s penguin population. In 1968, the Phillip Island Conservation Society was established in response to growing community concerns regarding accelerating development on the island.4

By the 1980s, concern began to grow among the island’s residents around declining penguin numbers. In 1984, community protests lead to the enactment of the Penguin Protection Plan which proposed a buyback of all 180 buildings and 780 allotments then on the Summerland Peninsula. The idea was that the area would be returned to natural habitat, with additional funds to be provided for little penguin research.5 $10.5 million was allocated to repurchase the properties, which was expected to take place over a 15-year period. However, it took a further 10 years beyond this for the final house to be purchased, in 2010. Over this period, the island’s penguin population increased from between 12,000 to 14,000 in 1984, to 36,000 in 2018.6

In 1988, as part of Australia’s bicentennial celebrations, a new visitor centre was opened on the site of the Summerland Peninsula’s former golf clubhouse. Designed by Daryl Jackson Architects, the new centre elevated visitors’ experience of the penguin parade and was the start of busloads of tourists heading to the island every night. Tourist demand continued to grow over the following years with Phillip Island Nature Parks (PINP) being established in 1996 to manage more than 1,805 hectares of land across the island.

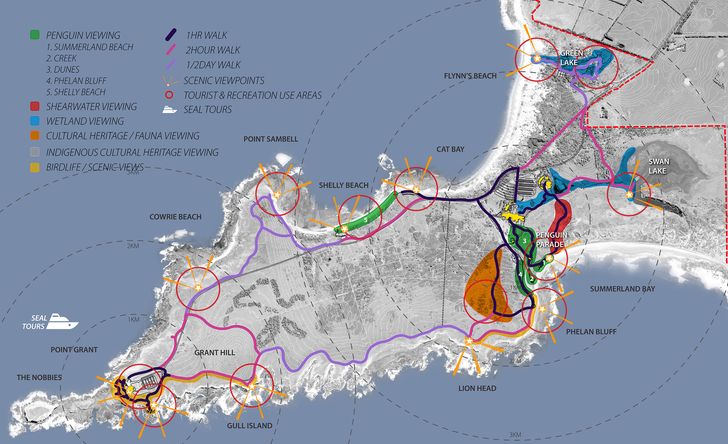

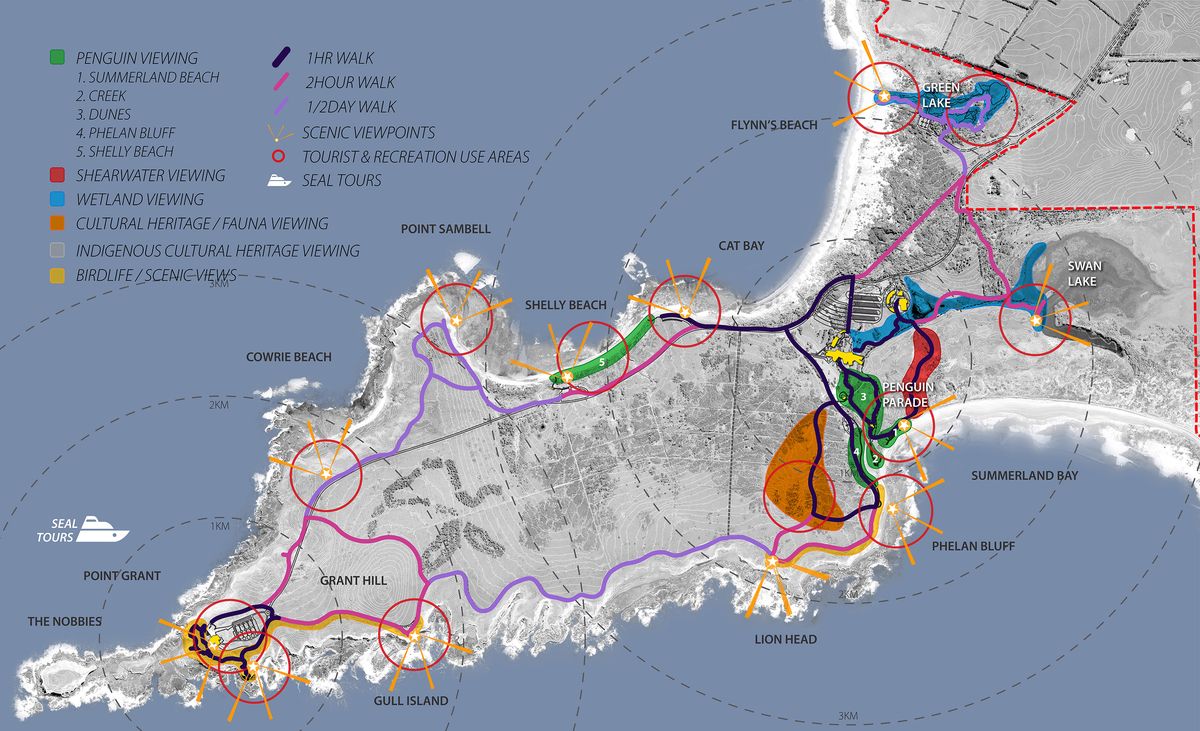

An image from the Summerland Peninsula Strategic Plan by Tract, the first in a series of plans that set new directions for the Summerland Peninsula.

Image: Tract

Tract’s Summerland Peninsula Master Plan established a vision for the area as an ecotourism destination with environmental management, education and research programs.

Image: Tract

Following the purchase of the final blocks at Summerland in 2010, a masterplan was prepared to establish a new vision for the peninsula. Tract landscape architect Mark Reilly led the project team in the preparation of the Summerland Peninsula Master Plan. He describes the project as being a critical point that “allowed for a strategic reassessment of existing infrastructure patterns and operational models.” The result was a “series of projects that relocated the visitor centre to a location that allowed an expansion of wildlife habitat, created new viewing opportunities and developed new infrastructure design and siting standards.” This led to a change in the way the community and visitors interacted with the landscape. Reilly recalls the period of planning and design also allowed for a “redefinition of public access to the peninsula and for the experience of the peninsula landscape to take on a wider role.” These projects emphasized Summerland as a place with many destinations, attractions and landscapes, rather than as just an evening “attraction” – the Penguin Parade. The award-winning Penguin Plus viewing area completed in 2016 by Tract Consultants with Wood Marsh Architecture was one project to come out of the masterplan.

The Phillip Island South and North Coast Key Area Plan (2014) by Inspiring Place with Ecology and Heritage Partners is another example of the PINP taking a holistic approach to the area’s land management. Inspiring Place director Jerry de Gryse felt a key success of the project was the “commitment by PINP to meaningful and iterative community engagement. The latter meant that we could put ideas forward, test them and refine them during the course of the project to achieve community acceptance – particularly for the more aspirational ideas we were proposing.” De Gryse felt this approach meant the studio “was able to and encouraged to put our conservation values at the forefront of [everything] we did on the project [and] mesh these with our understanding of visitor and resident need for access to quality experiences of the island’s coastline, woodlands and wetlands.” Landscape architects that were instrumental in the governance of PINP during this period of strategic planning and investment included Catherin Bull (active 2009–2015) and Andrew Paxton (active 2012–present).

A ground-level viewing window embedded into the platform allows visitors to experience the parade of penguins close-up.

Image: Phillip Island Nature Parks

The contoured forms of the Penguin Plus viewing area nestle gently within the coastal environment and offer diverse views of the local flora and fauna.

Image: Tract

The opening of the $58.2 million Penguin Parade Visitor Centre by a consortium led by Terroir with consultant practices AECOM, Tract Consultants, Thylacine, Steve Watson and Partners, UFD, GTA Associates and Doug and Wolf in 2019 was both a celebration of the achievements of the past, as well as the beginning of a new future for the island. The project doubles the size of the existing visitor centre and is projected to cater for 840,000 visitors annually by 20307, up from 700,000 in 2019. Protection and enhancement of environmental values has enabled the creation of a successful nature-based tourism. The Phillip Island and San Remo region generates approximately $339 million in direct visitor expenditure each year, contributing 39.4 percent of the region’s gross regional product and making the area’s economy the most reliant on tourism in Australia. This is forecast to grow from 1.85 million visitors in 2015 to 3.4 million by 2035, which would be worth more than $1.1 billion annually. The natural environment will be the main driver of this growth.8

The Penguin Parade Visitor Centre that opened in 2019 double the sizes of the existing visitor centre and will cater for the rapidly growing number of tourists to the region.

Image: Tract

And then COVID-19 hit. While the penguin parade was closed for most of 2020, the environmental management of PINP staff was able to continue thanks to a $8.8 million Victorian government grant.9 In a stroke of genius, the site infrastructure was used to create a livestream of the Penguin Parade for 112 nights, which was seen by more than 25 million people in nearly 100 countries.10

As pandemic restrictions are slowly lifted and tourism starts to return, Reilly notes there are broader challenges emerging for iconic coastal destinations: “The coastal edge of Phillip Island tends to be ‘all things to all people.’ Phillip Island is perhaps at a tipping point. There will be opportunities to design better coastal settings, connect places and create new experiences; to spread people out and create better settings for special events and community uses and to achieve contemporary design standards. The coast will always be the defining quality of an island – its icon – but there will be limits to how many people can use these coastal areas without diminishing the quality of the environment or the experience of other users.” Reilly sees strategic documents as being critical to achieving long term outcomes for the island and its iconic natural experiences. “It’s important for decision makers to deal with the present, but always with a view to longer term strategic directions, perhaps [while] retaining a ‘long life, loose fit’ approach that allows for future change.”

Just as coastal environments are ever-changing, new challenges and environmental pressures are emerging. The impacts of climate change and sea level rise will impact our coasts and ecologies. A more unusual challenge for Phillip Island has resulted from the successful eradication of foxes on the island in recent years. This has enabled the reintroduction of native species on the island (such as the eastern barred bandicoot), but has also led to an explosion of Cape Barren geese, which is having a detrimental impact on local farming practices. The Victorian government is exploring the culling of geese, which has the potential to create a new “bush tucker” industry similar to the one on Tasmania’s Flinders Island which encountered a similar problem in the early 2000s.11

History proves the Phillip Island community has the ability to adapt to protect the local environment, which also provides the community with social and economic benefits. The management of the island’s unique landscapes offers a model for sustainable tourism that could be replicated in other parts of Australia. The successes of the past are evidence that a holistic appreciation of ecological, social and economic values is required to achieve balanced and lasting outcomes.

1. “Progressive Cowes. Island’s Notable Day. Two New Buildings Opened,” The Argus, Monday 10 December 1923, 12, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2001265?searchTerm=phillip%20island%20penguin# (accessed 23 February 2021).

2. “The Ideal Summerland: Golf History on Phillip Island,” Society of Australian Golf Course Architects website, https://sagca.org.au/the-ideal-summerland-golf-history-on-phillip-island/ (accessed 23 February 2021)

3. “There’s only one Summerland and it’s here on the Nobbies, Phillip Island,” The Herald, Wed 21 December 1927, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/243972508/26539133 (accessed 23 February 2021)

4. Phillip Island and District Historical Society website, http://pidhs.org.au/essay/67 (accessed 23 February 2021)

5. G Newman, “Studies on the Little Penguin Eudyptula minor in Victoria: An Introduction” EMU vol 91, 1992, 261–262, https://www.publish.csiro.au/mu/pdf/MU9910261 (accessed 23 February 2021)

6. Fiona Pepper, “When Philip Island penguins won and land owners lost,” ABC News website, 8 April 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-04-08/phillip-island-when-penguins-won-and-land-owners-lost/9464698 (accessed 23 February 2021)

7. “Terroir’s Penguin Parade visitor centre opens,” ArchitectureAu website, 29 July 2019, https://architectureau.com/articles/terroirs-penguin-parade-visitor-centre-opens/ (accessed 23 February 2021)

8. Bass Coast Shire Council, Phillip Island and San Remo Visitor Economy Strategy 2035, August 2016, https://d2n3eh1td3vwdm.cloudfront.net/general-downloads/Strategies/2016-08-29-FINAL-Phillip-Island-San-Remo-Visitor-Economy-Strategy-2035-Growing-Tourism.PDF (accessed 23 February 2021)

9. “State’s $8.8 million lifeline for Phillip Island Nature Parks,” Sentinel Times website, 3 May 2020, https://sgst.com.au/2020/05/states-8-8-million-lifeline-for-phillip-island-nature-parks/ (accessed 23 February 2021)

10. “Live Penguin TV signs off as visitors return to famous Parade,” Philip Island Nature Parks website, 11 December 2020, https://www.penguins.org.au/news/latest-news/live-penguin-tv-signs-off/ (accessed 23 February 2021)

11. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Draft Phillip Island (Millowl) Wildlife Plan, Engage Victoria website, https://s3.ap-southeast 2.amazonaws.com/hdp.au.prod.app.vic-engage.files/2116/0463/2321/Draft_Phillip_Island_Millowl_Wildlife_Plan.pdf (accessed 23 February 2021)

Source

Review

Published online: 16 Jul 2021

Words:

Mark Frisby

Images:

Philip Island Nature Parks,

Phillip Island Nature Parks,

State Library of Victoria,

State Library of Victoria.,

Tract

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2021