Beyond Wild is the third monograph published by The Monacelli Press to cover the work of Raymond Jungles, after The Colors of Nature (2008) and The Cultivated Wild (2015).

Like a good garden, Jungles’ books have flourished with the passage of time. The latest is the most ravishing yet. Reading as a series of essays in garden and landscape planting design, it showcases 20-plus projects from the Jungles studio. All derive from the same hand, while each reveals a new way of working with plants.

The introduction by Michael Van Valkenburgh describes the experience of visiting the roof at 1111 Lincoln Road, Miami Beach, where Jungles created the well-known Sky Garden. Van Valkenburgh describes it as “one of the best gardens I have ever seen.” While it scarcely seems possible to evaluate a garden or landscape without such a visit, similar accolades might well apply to all the other projects featured in the book. Rarely is such beauty so well sustained.

The title of the book asks the reader to consider what it is that lies “beyond.” If the “cultivated wild” exemplified the artifice of a designed nature, “beyond wild” has only one realm: the beautiful, born of love, with plants central to the tryst. Jungles’ designs are unfailingly beautiful because their source is the perfection of plant forms. We might all ask ourselves as we work: Is what we are doing going to be beautiful? Truly beautiful? And if so, in what way?

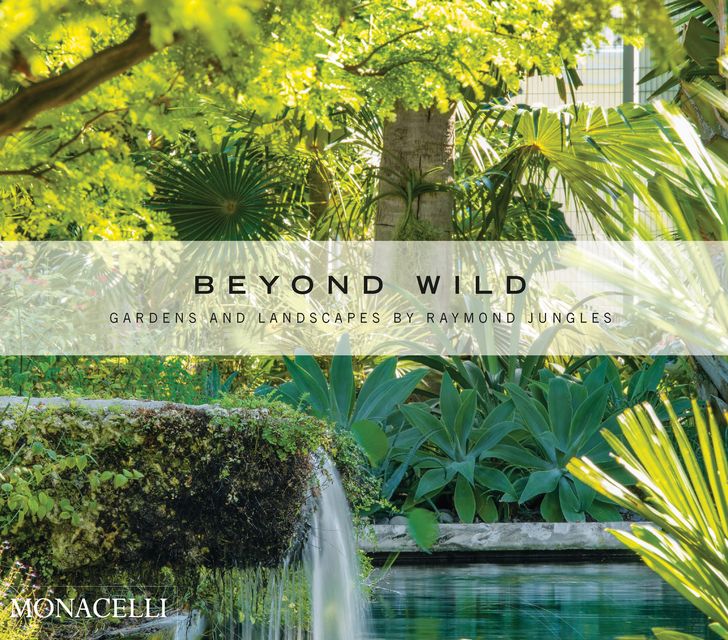

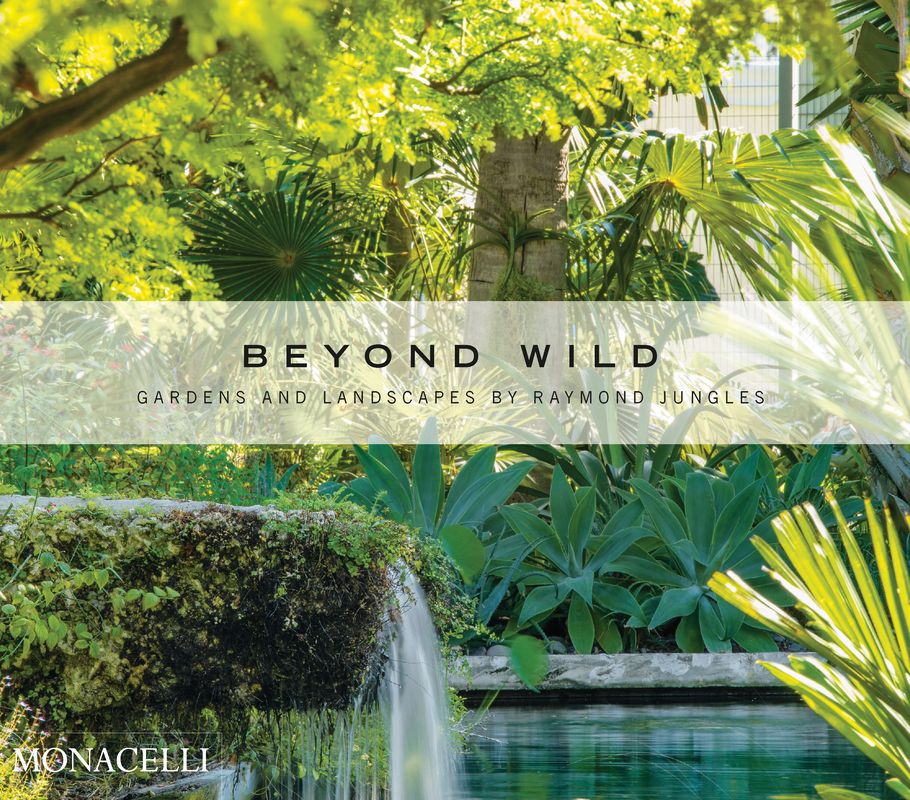

Beyond Wild: Gardens and Landscapes by Raymond Jungles

Just as the garden is central to Jungles’ design thinking, so it is central to his professional practice. His studio, featured in the book, is also a garden and place of research; a place where staff can dwell among plants. Like a mini Sitio, the Brazilian home of Roberto Burle Marx, the Jungles’ studio experience has become the nucleus of how to “think with plants.”

The ability to imagine the presence of a plant in glorious detail, and then others, side by side, and then to think about growth and potential, is a special skill. In the eighteenth century science of Goethe, this practice is known as “exact sensorial imagination”1; it is taught at Harvard as a form of meditative visualisation. Landscape architects in Australia might well benefit from such practices. This author is no exception.

It is this way of thinking that brings the multi-stem Alluaudia procera to a drifting scene of grasses in the Coccoloba Garden (2018), or the subtropical Ficus maclellandii “Amstel King” to the composition of the atrium at the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice in New York City (2019). Here, Jungles has re-envisioned Dan Kiley’s original 1967 design, using deliberate planting relationships and scientific innovation to sustain growth in very challenging conditions. Jungles’ projects are now found far and wide, including public projects like the Florida Garden at the Naples Botanical Garden in Florida (2017) and the seasonal Modernist Garden at New York Botanical Garden (2019). A planted reverie on the work of Burle Marx, the picture-perfect Modernist Garden brought all the diversity of tropical rainforests to central Manhattan.

The Modernist Garden (2019) at New York Botanical Garden, brings the diversity of a tropical rainforest into the heart of Manhattan.

Image: Barrett Doherty

Jungles’ studio in Florida is a garden and place of research, where designers can dwell and learn how to “think with plants.”

Image: Robin Hill

In Australia, the idea that one could teach “thinking with plants” is a radical one, but the return of Julian Raxworthy to lead the University of Canberra’s landscape architecture program is a sign of new hope. Raxworthy’s “manifesto for the viridic”2 parallels the working method of Jungles. Raxworthy’s thesis that plants and designers are “equals” uncovers the lost voice of plants in our work, while Jungles reveals beauty by allowing plants to speak their own designs. Jungles’ view that the plants themselves are the design is the source of the beautiful in his work, and it is the “beyond’ that we seek.

In Australian design schools today, it is surely the role of teaching staff to initiate a love of plants, to follow Raxworthy’s manifesto and to once again align landscape architecture with the garden. Yet many universities list no subjects – or very few – in their course guides. The Australian discipline has veered far from the nourishment of its origins when diversions such as urban geography and mapping have replaced the heart of our enquiry. Students need so much more. Raymond Jungles’ books are part of the answer; they show what is possible with pure, intense and resonant planting design that speaks to the heart of landscape architecture.

Sky Garden demonstrates Jungles’ approach, where plants are the source of the beautiful.

Image: Robin Hill

In other disciplines in Australia, such as law and medicine, students must pass a number of mandatory core subjects to become a practitioner. It is well past time for course design and accreditation in landscape architecture to give voice back to the garden, to listen once again to the land.3

1. Goethe (1795) in Douglas Miller (ed.), Goethe: The Collected Works (Scientific Studies, Volume 12), (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995). See also the discussion of Goethe in Henri Bortoft, The Wholeness of Nature (Great Barrington, MA: Lindisfarne Press, 1996).

2. Julian Raxworthy, Overgrown: Practices between Landscape Architecture and Gardening (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018), Chapter 8.

3. See James Sinatra and Phin Murphy, Listen to the People, Listen to the Land (Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, 1999).

Source

Review

Published online: 22 Jul 2022

Words:

Michael Wright

Images:

Barrett Doherty,

Robin Hill,

Stephen Dunn

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2022