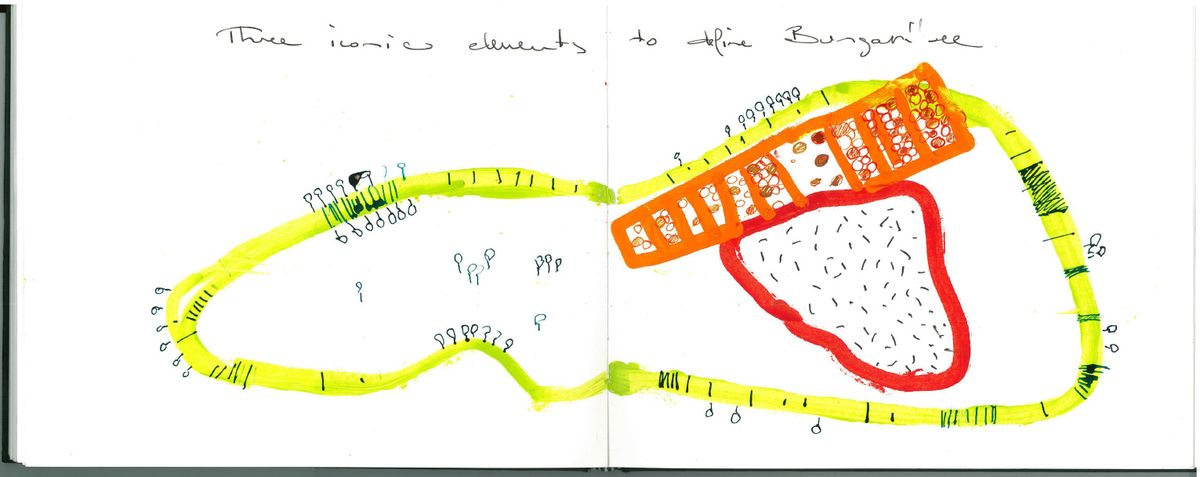

The placename Bungarribee has been linked to the Darug and Gundungurra peoples, variously translated from bung, meaning “creek,” and garribee, meaning “cockatoo.” As with many Australian Indigenous placenames, there are often multiple, nuanced meanings that reflect evolving language and cultural practices as well as misinterpretations stemming from the beginning of colonial dispossession. James Kohen writes that Bungarribee continues to have an evolving meaning based on southern dialects and contemporary local Indigenous naming practices. Local elders often refer to Bungarribee as “camp site beside a creek,” whereas the only recorded meaning is “resting place of a king.”1 My point here is that like its placename, the landscape of Bungarribee Superpark reflects emergent and constantly evolving readings of site – nuanced, literal, translated, layered and contested.

James Mather Delaney Design’s (JMD Design) recently completed strategic masterplan and works for Bungarribee Superpark acknowledge these multiple meanings and the various histories of the site. The design also anticipates future adjacencies, including Sydney’s new zoo and suburban and medium-density housing as well as transport activity centres. Overall the design is bold yet graceful, managing to be overt and legible while simultaneously nuanced, abstract and playful. Most of all, it is capacious and unflinching – embracing the scale of the Western Sydney Parklands landscape. While much of the actual space of the park is dedicated to restoring and protecting the central grasslands and increasingly rare ecotones (riparian and open canopy forests in Western Sydney), JMD’s approach to revegetation celebrates abstracted notions of bush and overtly constructed ecologies. Grassland areas are juxtaposed with inventive play environments, picnic and gathering facilities, a multi-programmable events lawn and mound, a small amphitheatre, kiosks and other amenities. The park is encircled by an intertwining path that passes through, above and adjacent to its heart.

Grandly scaled billboard-like structures function as wayfinding devices. Image:

Simon Wood

At the park’s entrance, an abstracted red gum forest stands beside a deep red billboard-esque entry portal for cars, with a black-and-white animistic entry portal for pedestrians. These features are visual markers, but more importantly their scale and height frame the landscape while coaxing the viewer to look up into the sky and trees. They hint at previous occupations and perhaps signal an ongoing fascination with Parramatta Road, Western Sydney’s version of the Las Vegas observed in Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour’s 1972 book Learning from Las Vegas . Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour’s “ducks” – in which space, structure and program are dictated by an overall symbolic form – and “decorated sheds” – in which structure is more generic and ornament is applied independently – are not rare in Western Sydney. However, rather than thinking of them strictly as buildings, we can apply these labels to landscape architectural follies, pavilions and site amenities. They also provide an interesting dichotomy to consider when thinking about typical landscape programs such as bioswales, parking lots, forests and grasslands. I am deliberately posing a binary here to frame some of the design work and the aspirations at Bungarribee Superpark, because it casts a new light both on the ordinary or everyday programmatic requirements in landscape architecture and on the ways in which designers might begin to conceive of their projects.

Here, JMD deliberately conflates the duck with the decorated shed into “duck sheds.” The entrance features are distorted both by their thin, tilt-up billboard quality (ducks) and by their literal framed portal openings (decorated sheds). The picnic shelters by Stanic Harding Architecture and Interiors, dotted through the centre or apex of the project, provide another interesting reading of this dichotomy. Their sculptural folds call to mind origami birds and butterflies or perhaps even evoke an abstraction of aeroplanes, which links directly to one of the site’s pasts as a World War II airfield, but the forms do not obfuscate their program. They clearly provide shade and shelter in an open, expansive landscape as well as a convivial place for pausing.

Mist descends over the expansive grasslands; the origami-like picnic shelters provide gathering points for visitors.

Image: Simon Wood

Two linear forests, with over 6,000 trees, retrace and extend former runways. The forests combine and intermingle with built elements while defining edges of the larger landscape. They are liminal spaces; on the surface they appear to be ducks (symbolic forms recalling and marking the past), but in reality they provide much-needed shade and respite from the openness that abounds. The carpark and the site’s requisite bioswales are decorated sheds; they are standard and functional so as not to compete with the larger gestures, but their materials are refined and well-heeled. This attention to detail and material presence is rather unexpected in light of the industrial heft elsewhere on the site, a characteristic that adds to the design’s overall richness. Most present in the amenities block and the footpath bridges, it is not fussy or finicky, but instead strangely sumptuous and vibrant in such a big landscape – an unexpected splendour.

A bright, boldy patterned, and adult-scaled cubbyhouse complete with slides is suggestive of post-industrial ruins. Image:

Simon Wood

Industrially scaled playspaces are juxtaposed with areas of grassland, picnic and gathering facilities and other amenities.

Image: Simon Wood

Throughout Bungarribee Superpark there are various points of intensity, all of which occur without trying to overpower or distract from its central grassland and Eastern Creek’s riparian corridor. JMD’s design protects, leverages and extends the remnant landscapes, while playfully and confidently stitching in new elements through thickened thresholds. Western Sydney is undergoing enormous development at the moment, at a mind-numbing pace. Bungarribee Superpark is an astute, unapologetic landscape that balances the nuanced and the overt to celebrate this transformation.

1. James Kohen, The Darug and their neighbours: The traditional Aboriginal owners of the Sydney region (Blacktown: Darug Link in association with the Blacktown and District Historical Society, 1993), 12–13.

Credits

- Project

- Bungarribee Superpark

- Design practice

- JMD Design

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Anton James, Ingrid Mather, Don Kirkegard, James Grant, Claire Broun, David Warwick, Nick Brown, Riley Field, Ali Gates, Arlyn Romero, Joe (Lin) Zisheng, Tian Li, Natalie De Soussa, Josh Abbott

- Consultants

-

Civil engineer

J. Wyndham Prince

Construction Daracon Group, Fleetwood Urban, Antoun Civil, Landscape Solutions (entry structures)

Electrical engineer Lighting Art and Science, Simplex Engineering (ASP3)

Playground certifier CCEP Consulting Coordination

Quantity surveyor John J Hollis and Partners

Shelters and amenities Stanic Harding Architecture and Interiors (architecture), Cantilever Consulting Engineers (structural engineering), H4DA (hydraulic engineering), CD Construction Group (builder)

Structural and hydraulic engineers Northrop Consulting Engineers

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Design, documentation

36 months

Construction 22 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens, Parks

- Client

-

Client name

Western Sydney Parklands Trust

Source

Review

Published online: 17 Jun 2019

Words:

Sueanne Ware

Images:

Anton James,

Simon Wood

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2019