The Gehry-designed Dr Chau Chak Wing building at the University of Technology, Sydney played host to the 2018 Landscape Australia Conference.

Image: Anna Kucera

The Landscape Australia Conference began with a lively and impassioned presentation by landscape designer Chang Huai-yan, the director of the Singapore-based practice Salad Dressing. Offering up many dedications to his mentor – the enigmatic, Australian-born, Balinese-practising garden designer Made Wijaya, under whom he studied – Chang took us into the curious relationships of landscape architecture in the Asian tropical context. Chang recounted how elements of Australia and Australiana, from artists Brett Whiteley and John Wolseley to May Gibbs’ Snugglepot and Cuddlepie , have infused his tropical practice via Wijaya. Illuminating the way in which tropical garden aesthetics respond to a different set of criteria from that of gardens emerging from the Western philosophical tradition, Chang said, “In the West we seek an answer to our questions, while in the East, a question is often answered with more questions.”

Prapan Napawongdee and Yossapon Boonsom of Thai practice Shma proposed novel ways of considering the territory of the city, focusing on the often unhappy meeting between a fluid terrain and the solid city. In monsoonal Bangkok, this “meeting” often incurs massive disruptions to daily life. Shma proposes new tools for working within this volatile politico-ecological situation, permitting landscape to become a “change agent.” Moving beyond the pre-existing blurring of the boundary between water and the city to find ways to “live with the river,” their design practice seeks to work at the confluence of development pressure and ecological concerns. Napawongdee and Boonsom’s landscape approach is that of mediator between design and the public domain, opening up a dialogue among stakeholders. This means giving “everyone involved a voice” – developers as well as the community – an insightful and novel alternative to traditional community consultation practices.

New York-based artist Mike Hewson gave a talk on a public artwork he recently installed at a mall in Wollongong.

Image: Anna Kucera

New York-based Mike Hewson began the second session by offering a shift in the mode of landscape practice. He presents himself as an artist and a structural engineer, not a landscape architect, and has had no formal design training. The work under discussion, Illawarra Placed Landscape , was commissioned as a public art project. To an audience primarily made up of landscape architects, however, this project came across as utterly landscape architectural in nature, form and ambition. It is a witty and sensitive collage, rich in a dialectic maturity not often seen in landscape projects in Australia. It also encompasses an ecological and geologic sensitivity that goes far beyond mere representation, such that the work was able to access the subtle spatiotemporal qualities of the landscape of the Illawarra region. A robust plenary discussion centred on how the discipline might reposition itself, through other disciplinary frames, in order to gain similar creative autonomy and regulatory freedom.

The muddy reality of a dedicated landscape practice revealed itself nicely in the presentation by Jungyoon Kim of South Korean practice Parkkim. Parkkim displays an attentive commitment to the quality and integrity of its projects, values that are tested in the Korean context, where construction and politics are overwhelmingly given preference over the intentions of the landscape design once the construction phase begins. As an example of the great care shown by the practice for the integrity of a project, Kim relayed the story of how studio staff and Kim herself pulled up misplanted and incorrectly sourced water grass species in the early hours of the morning to ensure that the project would not be jeopardized by cost cutting. Water flowed in this presentation too, but across, down, beneath and through the delicate grate walkway detail of the Seoul Broadcasting System (SBS) Headquarters in the South Korean capital. As the setting sun reflected off the metallic surface, the design could be seen to choreograph the ephemeral. Kim finished her presentation by evoking her aim for her practice to reconcile Frederick Law Olmsted’s singular sublime moment with Ian McHarg’s boundless systems and processors.

John Lin of Urban Rural Framework, based at the University of Hong Kong, shared his practice’s balancing of a number of precarious but productive meetings between government, research and the community. The practice makes the most of China’s current climate of accelerated development to provide remote communities with built works that are robustly functional, sustainable and full of agency. Urban Rural Framework works as a mediator and a facilitator in the communities with which it engages, in an agile mode of practice where architecture is perhaps an added extra rather than the focused outcome. It responds to the nature of rural life and its complex social, ecological and economic concerns with vertical and horizontal gestures in which the architecture appears to emerge out of the collective desires of the people.

Shefali Balwani and Robert Verrijt of Indian practice Architecture Brio began their presentation in a climate completely counter to that of India. Their first slide showed images of the polders in the Netherlands, with windmills in full operation, mediating the lowland elevations. This utterly manufactured landscape with its tradition of urban hydrological landscape design played host not only to the education of the two practitioners, but to an approach to urban hydrology that they would later transport to their practice in India. Teamed with a reflection on the wild gardens of Piet Oudolf, this watery prelude gave us a hint about their approach to working with the untameable landscapes of India. Water revealed itself again as a material that carries great meaning, as Architecture Brio plays comfortably in what might appear to be conflicting realms of private luxury residential development and socially focused community infrastructure. This conflict is reconciled through material, water and light. The projects demonstrated a delicate harmony between the swampy, unmitigated flood terrains of southern India and the elegant material detailing of the dwellings, where the seemingly immaterial elements of light and water become themselves the driving materiality of the projects.

Landscape architectural practice in Asia might present, on the surface, a mode of working similar to that in Australia. As designers, we are primarily mediators of political, social and material flows and conflicts. What makes this mediation more dynamic and exciting, within the Asian context, is a greater fluidity of economy, governance and social formations than what we experience here. When we visited an Australian project, through Hewson, we could see that his practice relies on disciplinary slipperiness to provide fluidity and creative potential. This fluidity, both real and virtual, reveals landscape architecture in Asia to be an agile practice, discourse and culture. Landscape architects are not only designers of systems, form-makers or framers of nature. We intervene in the complex formations of urban, regional, rural and wild landscapes that grow ever more complex, fragile and dynamic.

The 2018 Landscape Australia Conference was held at the University of Technology, Sydney on 5 May 2018.

Source

Review

Published online: 23 May 2018

Words:

Louisa King

Images:

Anna Kucera

Issue

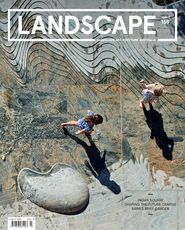

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2018