Julian Bolleter, Take Me to the River: the Story of Perth’s Foreshore, UWA Publishing, 2015.

As discussed in this excellent new book about Perth and its waterfront to the Swan River, current cultural theory argues that place is the confluence of space (as “neutral” territory) and meaning (as imbued by humans). Such a proposition immediately raises questions as to what meaning in relation to any space actually is and just how it is created. These are questions that Take me to the River addresses head-on, exploring the perceptions and imaginings of Perth’s immigrant and Indigenous cultures about the confluence of the land, where the central city sits, with the waters of what we now know as the Swan River. And a fascinating story that exploration is, relevant in its methodological approach and findings to Australia’s other capital cities, all of which address the water and all of which struggle to relate the expectations of their diverse resident cultures to a set of equally diverse natural ecologies. These are the battlegrounds where global expectations and local values meet.

The book’s author, Julian Bolleter, researches and teaches in the Master of Urban Design program at the Australian Urban Design Research Centre, the University of Western Australia, where he is an assistant professor. He has worked as a landscape architect in the UK, the USA and the Middle East and his PhD explored the design of Dubai’s urban landscape as a cultural phenomenon, interrogating the made landscape and its roots in various cultural positions and imaginings, globally and locally. Building from such experience, not only has the author used extensive archival research, compiling the drawings and images that support the text (the subject of a separately curated exhibition of the same name), he has also included records of interviews with and essays by a number of key players in the debates over recent decades about the major sites of contention along the waterfront. The story is told through presentation and analysis of this material, generally in historical sequence, although, notably, the “story” included in the Indigenous contribution is the last.

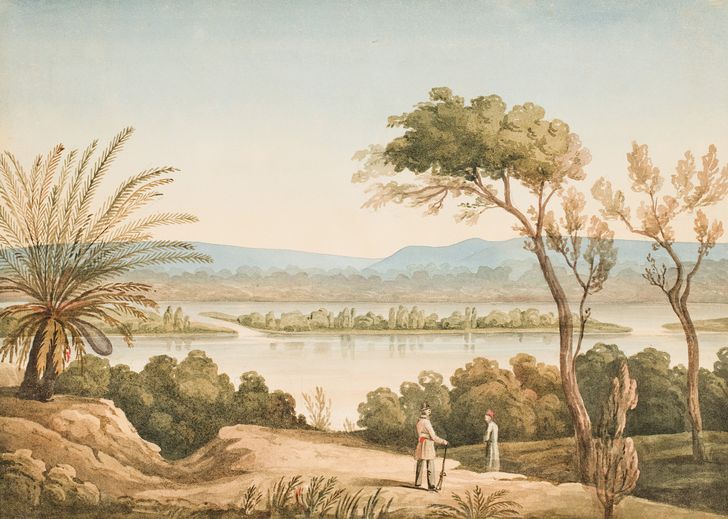

This painting from 1827 is reflective of how Perth was idealized in its beginnings, where descriptions of Swan River were inaccurate and topographical features dramatized.

Image: Swan River – View from Fraser’s Point, Frederick Garling, 1827

Similar to the beginnings of most Australian cities, Perth was initially imagined in the pastoral mould and from the 1820s “sold” on that basis to its earliest settlers. The story of early settlement in Perth is a hard one, the Arcadian imagery fading fast as the reality of poor soils, drought and isolation took its toll. Unlike Australia’s other cities, however, Perth was developed initially as a private commercial enterprise, sowing the seeds perhaps of its subsequent development mentality. Its story is one of a recurring idealism that infused not just the initial imaginings of place, but, as meaning has been progressively created, the subsequent decades and centuries. It is such recurring idealism, and its imaginings in urban and landscape form, that provide the central narrative here, as the hundreds of plans and designs for the city and its waterfront and the debates around them are laid out and analysed.

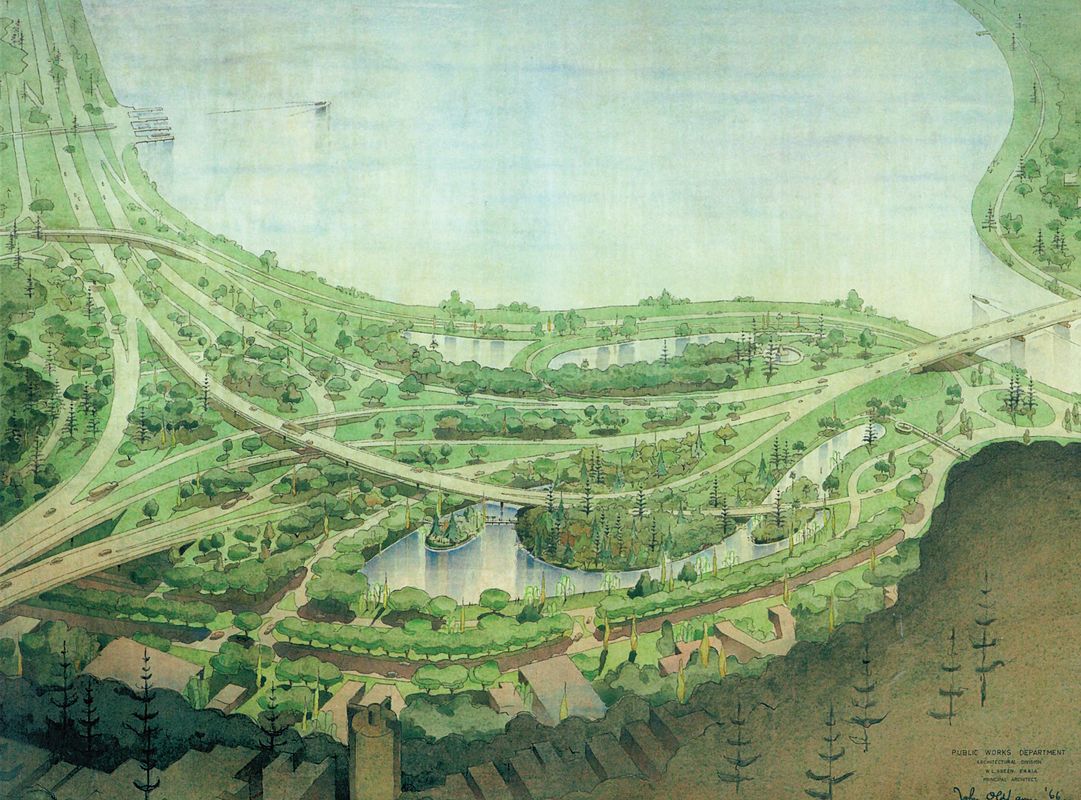

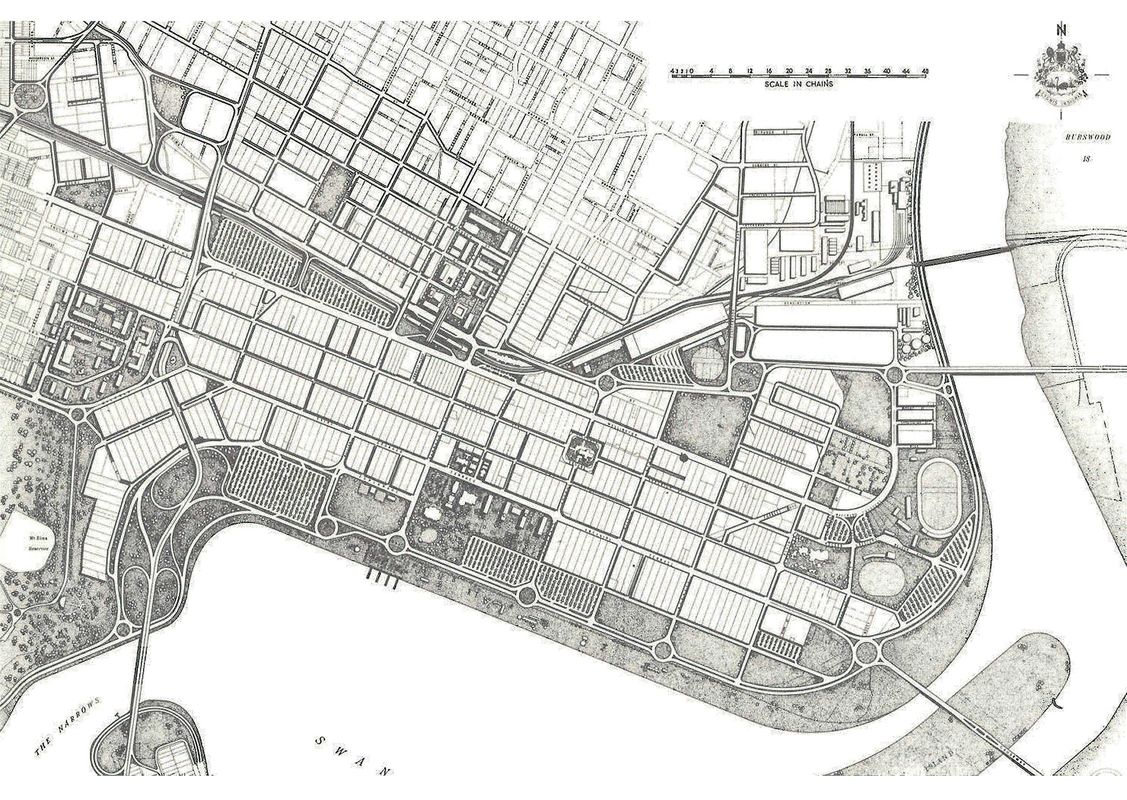

These endless debates provide the most revealing aspect of this story, illustrating how meaning has evolved for immigrant culture and contrasting sharply with the transcendent timelessness of Indigenous meanings for this place, Derbal Yaragan (the Indigenous name for Swan River), as explored in the final chapter. Every urban and landscape fad, fashion and value extant in the urban cultures of Europe and North America over the past two hundred years seems at some time or another to have been applied here, as newcomers struggled to re-imagine the junction between the modern city and the swampy fringes of what was, and what essentially remains, an estuary rather than a river. Starting with the Arcadian pastoral, we move through extended periods of reclamation to remove miasmic shallows, early imaginings of a waterfront park replete with a sweeping ornamental lake in the Arcadian style, experiments with the City Beautiful and amusement parks (think The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson), grand visions for encircling botanic gardens and zoological parks, parkway drives, an offshore island (Perth Island), mammoth engineering proposals for riverside drives and the Narrows Interchange that would dominate the horizontal landscape and isolate the city centre, urbanist proposals to reconnect the CBD to the water, romantically naturalist offerings that timidly reference Indigenous culture, and overtly postmodernist ones such as “Dubai on the Swan.” There are strategy plans, diagrams and masterplans enough to satisfy even the most determined visionary. Everything is here – in the mind and on paper. Some of it materialized – for better and worse – and thankfully, much of it did not, leaving for decades the foreshore as a tabula rasa ready for the next paper proposition. Except of course for the roads – most were built and are a story in themselves.

Planners, architects, urbanists, engineers and locals passionate about their city and its setting are all players in the book, including predictable recent contributions by Charles Landry and Jan Gehl and the many Australian landscape architects who have been involved in the design of the city’s waterfront over the years – John Oldham, George Seddon, Blackwell and Associates and Taylor Cullity Lethlean (TCL). A very young Perry Lethlean was, for example, a runner-up in the 1991 Perth City Foreshore Urban Design Competition, and TCL is the landscape architecture practice assigned to the massive Elizabeth Quay project underway today. The 1991 competition schemes of others, such as Andras Kelly (Tasmania), Dorrough Britz (ACT) and Environmental Partnership (Sydney), also appear. Heroes, villains? You decide.

A reader cannot but wonder how all these fantastical schemes must look to the Indigenous peoples for whom the very nature of this place is so resonant and its meaning so self-evident. For them, knowledge has little to do with such fantastical chatter. Their words form the title of this book. They know why this place is so powerful and describe in the final chapter “why you feel the earth speaking to you from this place … The water shimmers like scales; twisting, turning and weaving its bulky body across the plain, curving down to a wide path in front of the City of Perth, the bloated body of a well-fed Waakal or Rainbow serpent python. Leave yourself dreaming for now. You’ll be back soon.” The people of Perth, it seems, are always back, be it with yet another dream about what this place should be. The authors also speculate about how such sensibilities can inform urban action.

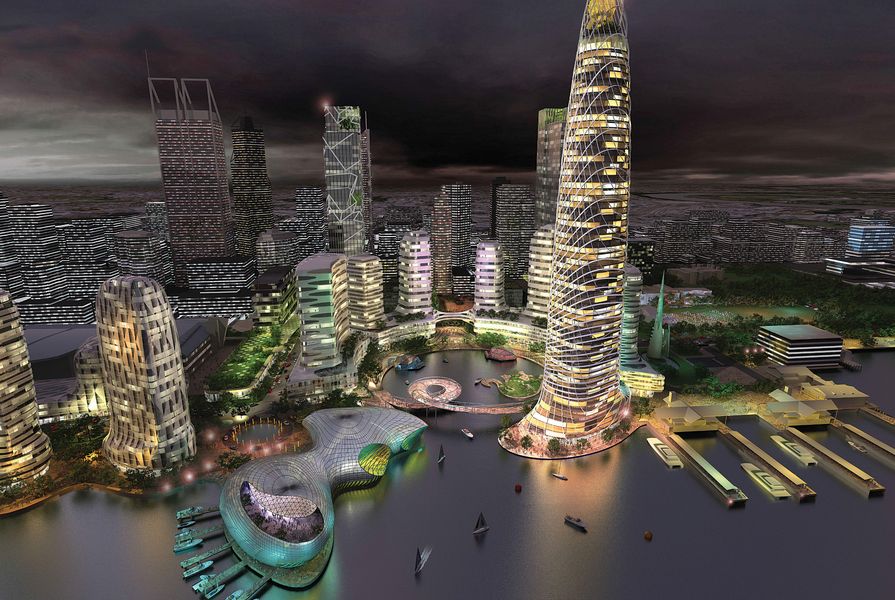

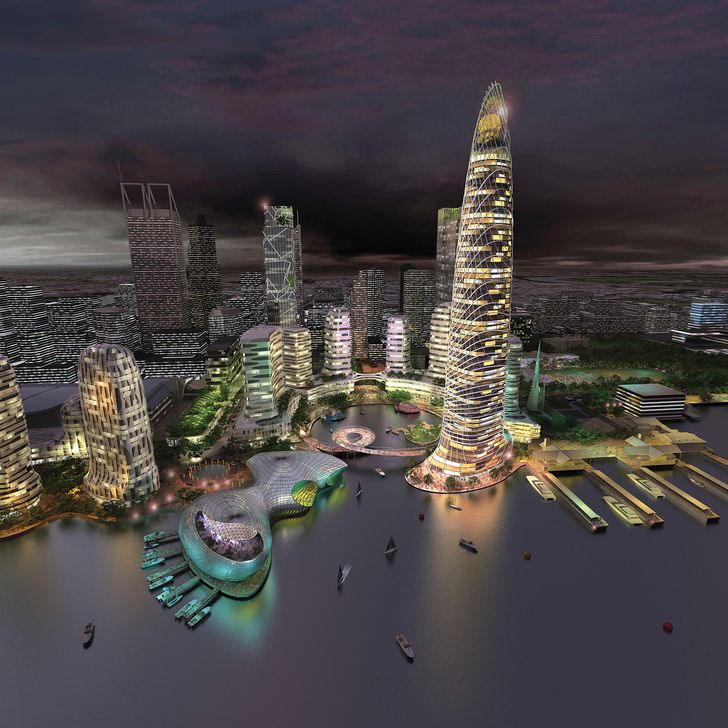

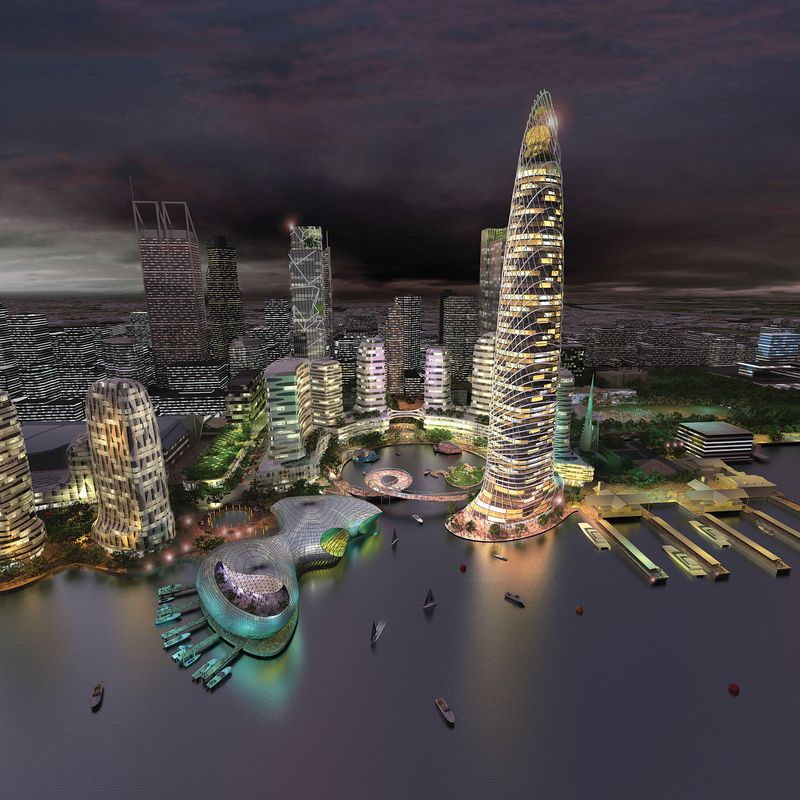

In Melbourne firm Ashton Raggatt McDougall’s (ARM) bold vision for Perth, the esplanade would be a highrise precinct where the river would be enfolded into an excavated circular inlet.

Image: courtesy of ARM

As revealing in their own ways are the contributory essays by Sean Morrison, Ken Adam, Richard Weller, Geoffrey London, Clint Bracknell, Len Collard, Dave Palmer and Grant Revell. For example, London, a former Victorian Government Architect, and Adam, chair of the provocative professional think tank City Vision, share their stories and views as to how a decision on the waterfront Elizabeth Quay project eventuated. Their stories are worthy in themselves of being required reading for urban planning and design students nationwide.

As an urbanist who watches with interest the ongoing debates about how Australian cities should relate to their waterways, I was fascinated by similarities and differences between the stories of Perth and the Swan River, and the stories of other cities. The premier of Western Australia, Colin Barnett, is quoted in the book as arguing for the Elizabeth Quay project (a rather odd project that fuses local sensibilities with the emasculated fantastical visions of Melbourne firm ARM Architecture) that it would be “an iconic, world class destination which signifies Perth globally in the 21st century,” rhetoric that parallels directly that of Queensland’s leaders arguing for the Queen’s Wharf development about to commence in the historic heart of Brisbane. And notably, both projects are named to assert royal imprimatur. While the political arguments may be similar, however, in Brisbane they are made against a totally different background discourse, one lacking the sheer quantum of visionary material that typifies the Perth story we learn about here.

While the reader might quibble about some of the book’s language (what does “generic waterfront” mean?), such concerns are of minor importance. This is urban scholarship at its best and one can only hope that as it reviews its research agenda in the light of current funding challenges, the University of Western Australia understands the value of work such as this, not only for the state but for urban professionals everywhere. UWA Publishing is to be congratulated on publishing this groundbreaking book. Perhaps it could consider encouraging similar explorations for all of Australia’s capital cities.

Source

Review

Published online: 4 Jul 2016

Words:

Catherin Bull

Images:

Swan River – View from Fraser’s Point, Frederick Garling, 1827,

courtesy of ARM

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2016