It’s been an odd time for campuses these last few years. Having been the engine room not just of the Australian university, but also of the cities that host our tertiary institutions, campuses have been hit by the COVID-19 pandemic in profound ways. While we are now back in the classroom on campus, moves such as blended learning – which predated the pandemic – have been accelerated by the necessary rapid uptake of online modes.

While there is much talk about working from home and its impact on the city, the same is also true for the campus, with lecture theatres being used less, fewer staff working in offices, and so on. Paradoxes exist: after formative years isolated online, younger students are desperate for campus life, but bring to it mental health issues developed during COVID-19, while mature students wanting to balance family, work and study would like to continue with the online options. Between architectural “design thinking” becoming a model for contemporary educational practice and a service industry stimulated by campus development, some of the core aspects of architectural design education – like the design studio – long ago became a bonus rather than a norm. These factors conspire to make it an interesting, if difficult, time to produce an authoritative account of the university campus in Australia.

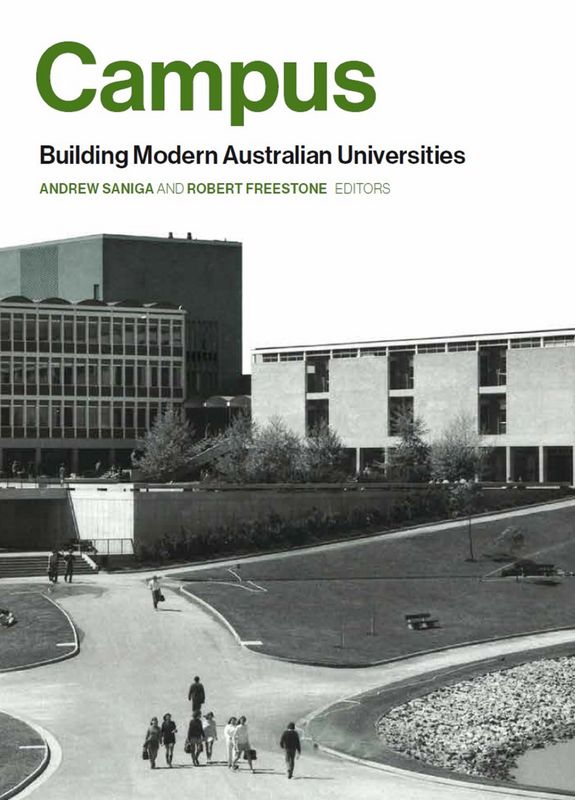

Campus: Building Modern Australian Universities is edited by the University of Melbourne’s Andrew Saniga and the University of New South Wales’s Robert Freestone, landscape architecture and planning historians respectively.

Image: Supplied

Published by UWA Publishing with its characteristic soft(ish) cover format, and weighing in at a hefty 450 pages, Campus: Building Modern Australian Universities is edited by the University of Melbourne’s Andrew Saniga and the University of New South Wales’s Robert Freestone, landscape architecture and planning historians respectively. Their backgrounds are relevant because much of the book’s interest stems from the broadness with which the topic is covered.

What might, 20 years ago, have been a study of the architecture and masterplanning of campuses is, today, quite different and says something in itself about the state of higher education in Australia and its vital but unpredictable progress going forward. Developed from a $300,000 multi-institutional Australian Research Council grant, the project (undertaken between 2016 and 2020) sought to “reveal the physical impacts of political, institutional, social and cultural demands through comparative thematic investigation [by] foregrounding landscape and site, establish[ing] new historical knowledge, identify[ing] campuses as catalysts for urban thinking, and demonstrat[ing] strategies for their conservation and adaptation to meet future needs in the tertiary sector.”1

In the introduction, Saniga and Freestone make a useful distinction between speaking about universities as institutions – which have gone through great dynamic change in relationship to policy and market forces – and campuses as places that house those institutions, and necessarily have more stability. They note that “to isolate the campus as a physical product devoid of its institutional identity would potentially sever an array of historical forces” (page xviii), thereby addressing a key aspect of the initial grant’s broader connection to Australian and international – political, cultural and social contexts. While this broader connection is vital, it also results in an opacity in the book. I was initially frustrated because my real interest lay in the landscape and architecture of the campus, a subject the book’s authors address but which, at times, seems secondary. However, from my experience as an academic of 25-odd years, these broader contexts truly describe the nature of higher education: generally reassuringly traditional and structured, but sometimes uncertain and occasionally innovative.

Being the outcome of a major grant, Campus’s contents would require a table for full comprehension: seven researchers from five universities (the greatest number from the University of Melbourne), all writing together in different constellations according to topic and expertise. The book starts with chapters on general context of a political, economic and cultural nature, informed by Australian history and geography. There are also links to global forces, tied to a growing sense of the particularly Australian public university and the funding challenges of maintaining that. Historical descriptions of the structuring of campuses by architecture and landscape follow, describing a transition from a singular formal vision, to collaborations, to interdisciplinary teams as the classical campus shifted to the bush. (The city and urban campus return at the end of the book.)

The Eddie Koiki Mabo Library at James Cook University in Queensland, 1968, designed by James Birrell.

Image: Courtesy of James Cook University archive

The section that explores key educational building types – libraries, lecture theatres and laboratories as well as student housing – is brief but represents perhaps the area of greatest change. These buildings comprise the cutting (or bleeding?) edge, where the broader contexts that frame the book most obviously play out. Toward the end of the book, “culture” is discussed in chapters on art and radicalism – the former now corporatized and subsumed under ubiquitous branding, the latter so far removed from contemporary student life that its violence seems nostalgic.

Campus was largely completed during the pandemic, and the final chapter by Cameron Logan, Hannah Lewi, Andrew Murray and Philip Goad concludes by suggesting that while the pandemic caused the university to go online, this trend was not new, and was not reflected in a reduction to new campus development and expenditure. Why? The writers’ suggestion that “the links between student perception and experience, research performance and institutional brand identity are a reinforcing loop for campus development” (page 341) rings true, but seems only a partial answer. As an industry, certain architecture practices have a regular role in shaping the contemporary university, either as masterplanners or as designers of “signature” buildings. With education practice in flux (we don’t do lectures anymore!), huge pressures on academic staff, poor employment practices by universities with little support, and an uncertain future regarding international students, massive funding for building on campuses can seem gratuitous, perhaps even desperate.

Walking Australian campuses, the historic legacy of innovation hints at a coherent golden era – described in the book – that is less and less present as gems of design, like Dick Clough’s Central Courtyard of lemon-scented gums at Macquarie University, are replaced by “distinctive” buildings. Once interesting outliers in the midst of thoughtful campus consistency and tradition, they have now aggregated to form theme parks of the spectacularly unspectacular. While it constitutes an important and thorough investigation into the physical and cultural nature of the Australian university, Campus ends as an open question: Can we build our way into a new future for higher education, or must something fundamental change?

1. Australian Research Council, Grant DP160100364 – The University of Melbourne;

dataportal.arc.gov.au/NCGP/Web/Grant/Grant/DP160100364 (accessed 29 November 2023).