The Adelaide Contemporary Design Competition sought proposals for a much-needed annex to the Art Gallery of South Australia. The new gallery, to be located on the vacated Royal Adelaide Hospital site adjacent to the Adelaide Botanic Garden, may be the first significant building on this prime redevelopment site. This is an opportunity for the state government to set the tone for regeneration and to build on Adelaide’s reputation for creativity, arts and festivals. The current gallery facilities are also at capacity.

The two-stage competition began in 2017 when expressions of interest were received from 107 design teams, made up of 525 firms across five continents. A shortlist of six teams proceeded to the second stage to develop concept designs. The teams follow the now familiar and problematic habit of well-known international practices pairing up with local architectural and landscape firms. The six shortlisted proposals were by: Adjaye Associates and BVN with McGregor Coxall; BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group and JPE Design Studio (with JPE’s in-house landscape architects); David Chipperfield Architects and SJB Architects with Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture (JILA); Diller Scofidio and Renfro (DSR) and Woods Bagot with Oculus; Hassell and SO-IL with Mosbach Paysagistes; and Khai Liew, Office of Ryue Nishizawa and Durbach Block Jaggers with TCL.

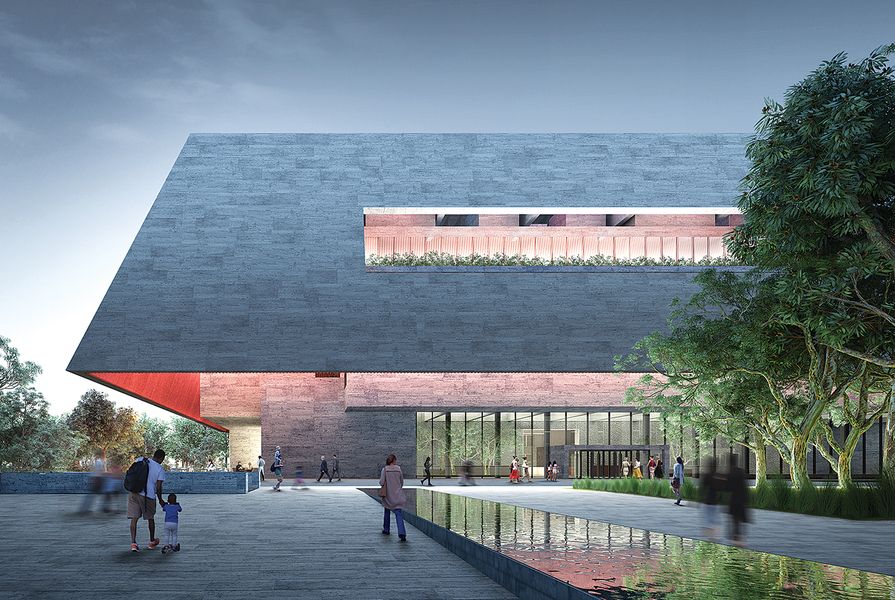

Proposal by Diller Scofidio and Renfro and Woods Bagot with Oculus, Pentagram, Right Angle Studio, Klynton Wanganeen, Dustin Yellin, Studio Adrien Gardère, Australian Dance Theatre, Deloitte, Ekistics and Katnich Dodd.

Image: © Diller Scofidio and Renfro and Woods Bagot / Malcolm Reading Consultants

In reviewing the competition, one can only rely on the publicly released material. We can guess at the interactions between the overseas firms and the Australian-based architects and landscape architects on the teams (only Mosbach Paysagistes is an overseas landscape architecture practice). I suspect some of the limitations of the landscape proposals may come from restrictive interactions with remote team members.

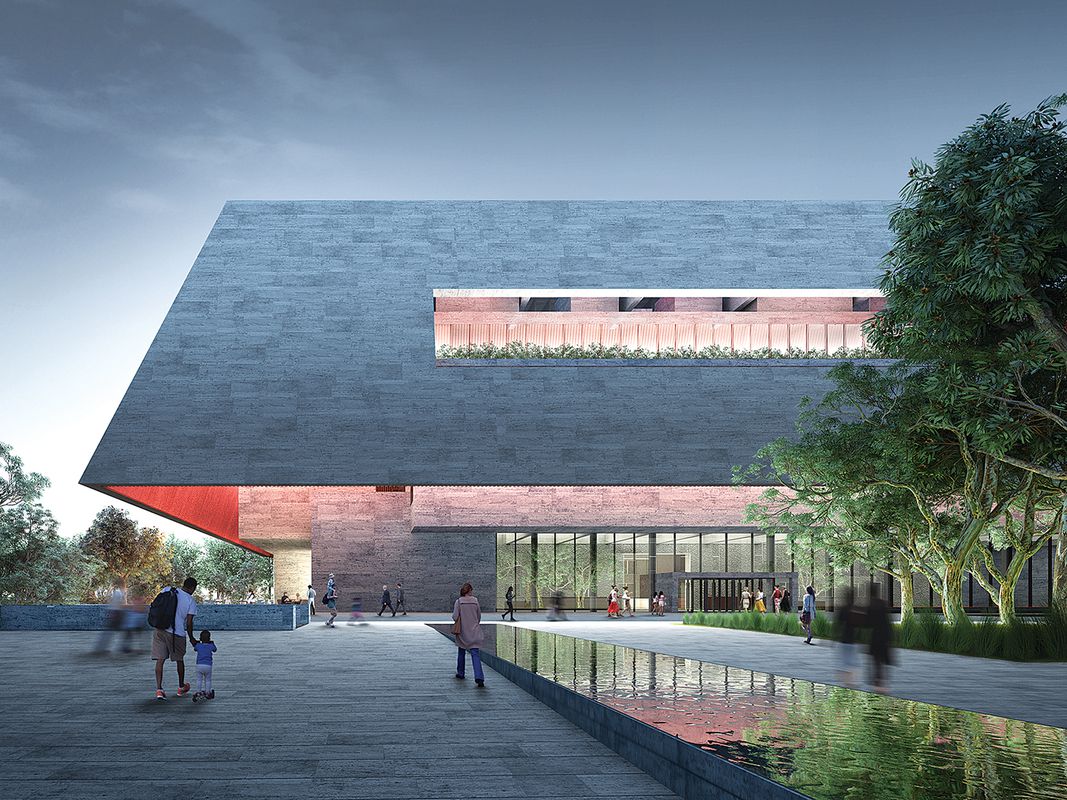

Proposal by Khai Liew, Office of Ryue Nishizawa and Durbach Block Jaggers with Masako Yamazaki, Mark Richardson, Arup, Irma Boom, Taylor Cullity Lethlean and URPS.

Image: © Khai Liew, Office of Ryue Nishizawa and Durbach Block Jaggers / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Proposal by Khai Liew, Office of Ryue Nishizawa and Durbach Block Jaggers with Masako Yamazaki, Mark Richardson, Arup, Irma Boom, Taylor Cullity Lethlean and URPS.

Image: © Khai Liew, Office of Ryue Nishizawa and Durbach Block Jaggers / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Also important are the context and timing. The competition straddled a state election and a change of government that may have dampened entrants’ enthusiasm. The nature of the brief suggested particular themes and perhaps encouraged proposals in certain directions. The setbacks defined a buffer with the botanic garden and a “human-scaled form of development,” as suggested in the competition brief, was considered desirable. It was suggested that while the building would necessarily be large, it was not to be monumental in scale. It seems contradictory to me that a large cultural building that will effectively “bookend” the cultural boulevard of North Terrace would not or should not be iconic. The schemes seem to be striving for a certain modesty, all with a subterranean component that subsequently keeps the height similar to its historic neighbours. Perhaps it is an Adelaidian quality to be so demure. I am sure that the subterranean element has many purposes, but with a site that slopes away from North Terrace, the schemes are most interesting in section, with extended landscapes taking good advantage of the grade change. Interesting opportunities were exploited, with several proposals developing an amphitheatre, terraces and gathering areas. There was much breaking down of indoor and outdoor space and of edges. This worked as a metaphor for a gallery that is transparent and sometimes literally accessible. The winning scheme by Diller Scofidio and Renfro and Woods Bagot with Oculus did this most simply and effectively, splitting the building and creating an all-day, all-night accessible space, the “super lobby” that extends to a stepped performance space.

In several proposals the amphitheatre has been reimagined with an Aboriginal focus, building on the Indigenous focus of the new gallery. Many teams included Aboriginal artist consultants. Considering the richness and diversity of contemporary Aboriginal art, however, surely there was greater opportunity to push the landscape conceptually under its influence? Many teams referenced Indigenous culture or experience, but the metaphors seem forced. For example, in what way really is the movement through the building like walking on the plains, as suggested in the Hassell proposal? Is it still appropriate or sufficient to have images of campfires to depict the Kaurna tradition of smoking ceremonies, as in the Adjaye scheme? I was struck by the idea of an interwoven building and landscape in the BIG scheme, but what if instead of JPE, BIG teamed up with Yvonne Koolmatrie, an Ngarrindjeri/Ramindjeri woman and expert in basket weaving whose works are represented in the gallery and incorporated her formal and conceptual contribution and insights?

Proposal by BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group and JPE Design Studio with United Natures, Arketype, BuildSurv, Virtual Built, Future Urban Group, Lewis Yerloburka O’Brien, Marijana Tadic, Erica Green, Peter Dungey, Brian Parkes and Lindy Lee.

Image: © BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group and JPE Design Studio / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Proposal by Hassell and SO-IL with Ali Cobby Eckermann, Arup, Australian Industrial Transformation Institute, Fabio Ongarato Design, Fiona Hall and Mosbach Paysagistes.

Image: © Hassell and SO-IL / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Similarly, the widespread pitch for exclusively indigenous plants and references to pre-colonial ecology – perhaps a belated recompense for the colonial project – is one too often seen in Australian landscape architecture. The issue is too vast and complex for such a singular response and the failure to acknowledge and explore the complexity of ongoing waves of species migration and adaptation is a continuing concern. The winning scheme was inspired by the “Kaurna concept of Minkunthi, meaning ‘to relax,’ with planting of a pre-colonised South Australian landscape linking the idea of the contemporary to Kaurna ecological and cultural history.” I think “linking” is the wrong approach here and a more discursive, less binary approach is required. The scheme is stronger when its authors talk of “[placing] the idea of the ‘contemporary’ within an expanded time frame.” This aligns with the curatorial requirement outlined in the brief for a “Gallery of Time [that] will illuminate Australia’s history as a cultural contact zone, offering fresh perspectives, highlighting similarities and differences.” But why can’t the landscape itself, the actual site of contact, also do this?

Proposal by David Chipperfield Architects and SJB Architects with Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture and Arup Lighting.

Image: © David Chipperfield Architects and SJB / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Rather than offering a mere green buffer to the adjacent botanic garden, the landscape proposals might have productively expanded on their diversity. (The botanic garden formerly occupied part of the site, traded in a land swap to expand the previous hospital.) This may have been the intention behind the incorporation of rooftop gardens in the BIG scheme and the inclusion of large planters at various levels in both the Chipperfield and the DSR schemes. Could the landscape itself have been considered more imaginatively as a contemporary artwork and place of interaction and agency with other, as yet unknown artworks and participatory activities, rather than as a pleasant green space for convivial events and informal gathering? The gardens of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra are a historic yet still powerful precedent for the poetic use of planting, with particular attention paid to textures of foliage, bark and ground planes alongside the then innovative siting of sculptures. The Chipperfield team with JILA has echoes of this in a no-nonsense “landscape garden” shown with conventional sculptures, responding literally to the brief’s use of the quite limited term “sculpture park.” But what would a truly contemporary, updated version be like? One hopes that the project will go ahead and that, in development, more nuanced landscape expressions will be found. I am looking forward to seeing how the DSR scheme’s ideas of the gallery as a “curatorial apparatus” and “cultural incubator”’ are enhanced in the landscape as the scheme is developed.

The Adelaide Contemporary International Design Competition ran from October 2017 to May 2018.

Source

Review

Published online: 15 Aug 2018

Words:

Tanya Court

Images:

© Adjaye Associates and BVN / Malcolm Reading Consultants,

© BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group and JPE Design Studio / Malcolm Reading Consultants,

© David Chipperfield Architects and SJB / Malcolm Reading Consultants,

© Diller Scofidio and Renfro and Woods Bagot / Malcolm Reading Consultants,

© Hassell and SO-IL / Malcolm Reading Consultants,

© Khai Liew, Office of Ryue Nishizawa and Durbach Block Jaggers / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2018