When the Graham Farmer freeway opened in 2000, it revealed to the citizens of Perth an elevated view of the Swan River and the river’s edge. The freeway and its tunnel (colloquially known as the Polly Pipe, after footy legend Graham “Polly” Farmer) expedited the masses from the northern suburbs to the south by tunnelling under the city’s north, crossing over the Swan and landing on a spongy, open expanse of an oxbow peninsula. The view from the road revealed to the east the glorious architectural carcass of the massive East Perth Power Station and to the south, across the peninsula, an underdeveloped neighbourhood of leisure – horses, golfers, paddlers, its primary residents. Despite its proximity to the CBD, the Burswood peninsula, this low-lying landscape of soft soil and reliable flooding, had for the most part escaped development.

The stadium and its surrounding precinct sit to the east of Perth’s CBD and are flanked on three sides by the Swan River.

Image: Peter Bennetts

In 2011, the Barnett government announced the Burswood Peninsula to be the site of Perth’s long-awaited Stadium. As early as 2005, a taskforce was established by the then Labor government to review Perth’s existing three arenas and confer with major sports codes to define and locate a stadium for the diverse sporting and entertainment requirements of Perth’s future. The recommendation was for one multi-purpose stadium with, three possible sites – an area adjacent to the East Perth Power Station, the existing Subiaco Oval site, and, almost a footnote in its announcement, the Burswood peninsula. Burswood was considered the costliest and most undesirable of the sites for several reasons – its geotechnical challenges compounded with no existing public transportation infrastructure, there were few vehicular access points and the immediate area surrounding lacked restaurants and bars for both pre and post-game conviviality. However, with the government’s recognition of the site’s potential to integrate with future planning, and momentarily cashed-up through revenue from the resource boom, Barnett managed to secure the site with a serious financial commitment to create a purpose-built public transport hub. This became a crucial obligation with a later decision to axe game day parking facilities – a concept very foreign to Perth’s car-loving sensibilities.

A network of walking and cycling trails weaves through the site, providing connections to the river and CBD.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Unlike the development at Perth’s other foreshore, Elizabeth Quay, this landscape move was relatively uncontentious and greeted with optimism. Notwithstanding any potential release of toxins and/or acid-sulphates through construction on this former rubbish tip site, it made good sense to build at Burswood. Whereas much of Perth’s awakened desire for density in the last ten years has been about filling in and going up – we are becoming accustomed to having views narrowed, ever-present shadows and a newly contained sky – the largness of this highly modified peninsula accommodated the scale of a stadium well. Ecologically the development and subsequent rehabilitation of this well-worn river’s edge is an environmental win strongly contrasting the mass destruction of the increasingly rare Kwongan habitat on Perth’s fringe.

An aim of the design was to rehabilitate the site (a former landfill) and address erosion issues along the river’s edge.

Image: Peter Bennetts

As the stadium grew from the Swan River’s banks, the resource boom subsided, and a Labor government came back to power. For a much-needed revenue injection, naming rights were sold, and the newly branded Optus Stadium is now open for business, hosting the first cricket Bash in January and Ed Sheeran’s Australian tour debut as the inaugural concert. As a venue, the stadium building is being tested and reviewed via social media and, with each subsequent event, the logic of building Perth’s largest venue without allowing for event parking comes under greater scrutiny. In this the design of the forty-one-hectare landscape surrounding the stadium is the critical link to connecting and servicing the stadium and helping to modify Perth’s car-centric attitude.

Hassell was the landscape architect for the project from masterplan to implementation. Even for Perth, the overall landscape is big and, except for the massive doughnut in the middle, unencumbered in views with lines of site across its expanse as well as to the CBD beyond. To the south and east, the landscape is very much designed to move people expediently. Unfussy and welcoming, a large forecourt area is designed to slow and calmly manoeuvre fans between the site’s two train stations to the main entry gates. This gentle aesthetic continues along to the southern bus hub and the newly opened Camfield pub. A pedestrian bridge across the Swan River, the Matagarup Bridge, is, at the time of writing, still under construction, but when completed will provide necessary access to East Perth. A 400-metre arbour of hyperbolic white ribs flows alongside the stadium, visually and physically leading fans from the bridge landing, around the stadium to the main gate’s forecourt on the east. At a distance the highly reflective arches seem pure folly.

Moving through the arches, however, the arbour reveals an appealing space that is nuanced and refined. Perforated metal shapes suspended from the well-positioned arches seem to have taken flight, like pieces of folded paper having caught a breeze. At the right time of day, this shadow play delightfully compels one to come along and follow the flock.

An airy 400-metre tunnel of white arches follows the curve of the stadium, guiding visitors from the bridge landing to the precinct’s main gate.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The entire site abounds with public art, mostly engaging with a bit of banal. Sitting within a landscape where the currency of identity has been pragmatically utilized to help fund some of the site’s larger landscape components, the greatest cultural imprint belongs to the Noongar people. While too often the didactic imperatives in public art and landscape architecture can be apologetic and trivialized, within this landscape the Noongar peoples’ narrative is ever present and proud. Kaya, Kim Scott’s multi-lingual poem etched into panels on the stadium’s facade, establishes the generous spirit of the engagement.

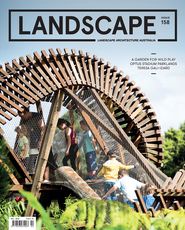

Aboriginal artist Sharyn Egan’s Waabiny Mia – Play House (partial view) is a woven rope structure based on a numbat tunnel that encourages free play.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Along the river’s softer edge, a parkland with subtle contours has been created around an existing river-fed lake, nestling the three-hectare Chevron Parkland. The six Noongar seasons provide the spiritual scaffolding for the terrific playground with stories and learning opportunities embedded sculpturally throughout. The contours create a rolling landscape of discovery with hundreds of salvaged logs casually defining spaces and play. In the brief time since its opening, children have taken full advantage of the lighter sticks left behind, assembling and reassembling the numerous lean-tos and mia-mias (temporary shelters) that now dot the landscape. Whadjuk artist Sharyn Egan’s Waabiny Mia, a playhouse based on a numbat tunnel, is fantastic as both a work of art and play structure. This area is dotted with simple well-designed picnic shelters and barbecues. Here Laurel Nannup’s modest yet beautiful art pieces, When I Lived In The Bush and Kulbardi, are inscribed by perforation onto metal screens that form part of the shelters. This will soon be a well-used and much-loved landscape.

A subtly contoured parkland and three-hectare playground have been created to the east of the stadium, around an existing river-fed lake.

Image: Peter Bennetts

As this visitor has now learnt, it is currently the Noongar season of Bunuru, described as Perth’s second summer. With hot easterly winds and sultry nights, one deficiency in the stadium landscape is made evident. For all its functionality, the landscape, particularly the more urbane precincts, simply needs more trees. It is unlikely that the stadium will ever feel nestled within a landscape, but twelve-metre expanses from tree to tree alongside paving is too great in Perth’s sun-soaked world. This aside, Hassell, having actively and successfully engaged with the stakeholders in a hugely extensive and complex consultation process necessary in creating public infrastructure, has delivered a highly useable and often engaging landscape. The stadium’s siting is good for Perth, with the river’s re-imagined edge once again becoming a landscape of connection and exploration.

Credits

- Project

- Optus Stadium parklands

- Design practice

- Hassell

Australia

- Project Team

- Anthony Brookfield, Sarah Gaikhorst, Hannah Galloway, Douglas Pott, Aysen Jenkins, Hannah Pannell, Nicholas Pearson, Jill Turpin,

- Design practice

-

Cox Architecture

Australia

- Design practice

-

HKS

- Consultants

-

Access and maintenance consultant

Altura

BCA and universal access consultant John Massey Group

Electrical engineer Wood and Grieves Engineers

Hydraulic engineer SPP Group

Lighting Philips Lighting

Public art consultants Form

Structural and civil engineering BG&E

Traffic engineers Arup

Waste management consultant Encycle

Wayfinding Büro North

Wind Engineering CPP

- Site Details

-

Site type

Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2018

Design, documentation 40 months

Construction 36 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Parks, Playgrounds, Public / civic, Sport, Tourism

- Client

-

Client name

Government of Western Australia

Website Government of Western Australia

Source

Review

Published online: 24 Sep 2018

Words:

Tinka Sack

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2018