The bushfires during the Australian summer illustrated climate change in the most heartbreaking way. Most would find it impossible to forget the images – burned koalas sitting on blackened earth, firefighters driving directly into raging infernos and terrified holidaymakers stumbling through that eerie red dawn. While many still quarrel over the facts, no one can deny that we are living in a hotter, more unpredictable and politically destabilized world.

Innovators respond by developing technologies that allow us to continue our way of life as if nothing has really changed. From cloud seeding to desalination, electric cars to renewable energy technologies, vegan meat to genetic modification, technology has become the panacea for all modern ills.

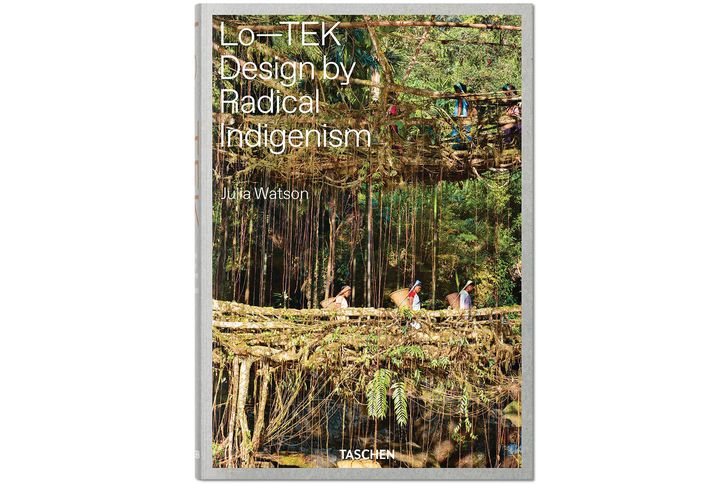

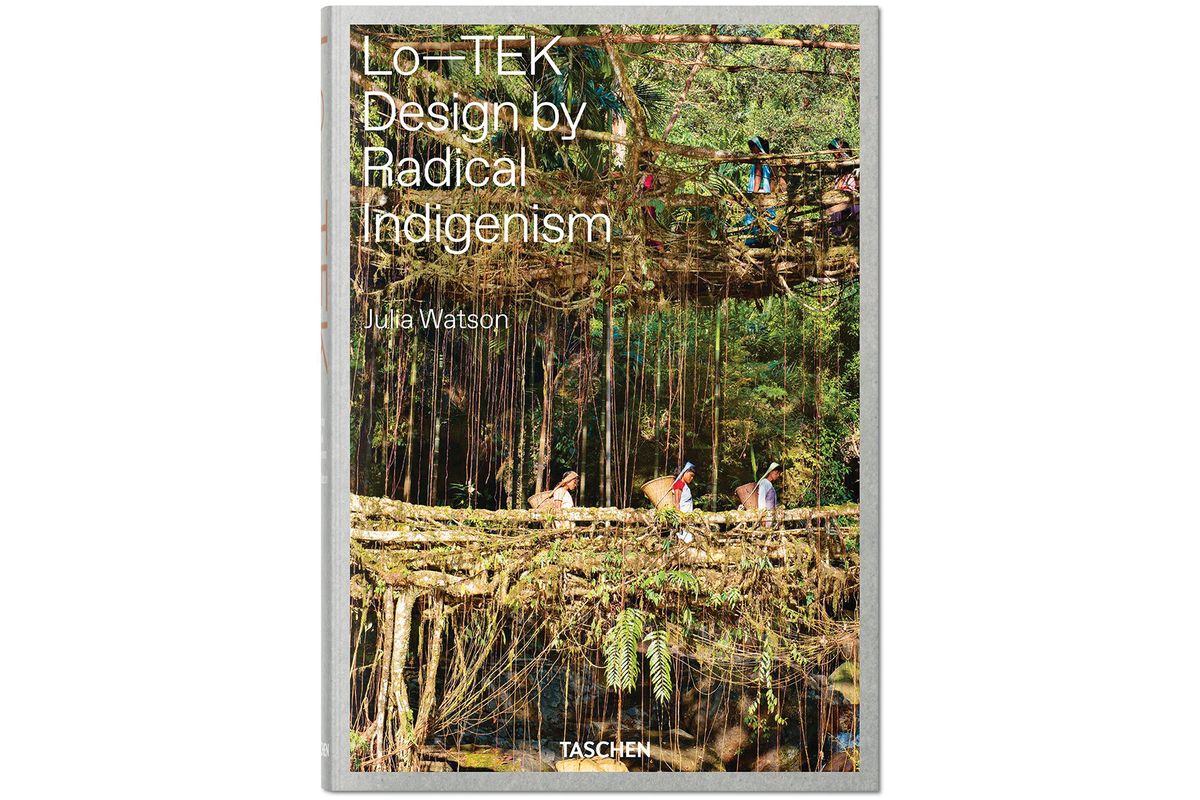

Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism by Julia Watson.

A far less common response has been to question our blind adoption of new technologies. This is surprising given that so many of these have contributed to the problems that we are currently facing. Such a response might be considered radical, because it questions the underlying anthropocentrism upon which many Western economic and social systems are based. Still, do alternatives exist? How might we possibly provide for the vast numbers of people now on Earth, without the use of new technologies?

Such challenging questions have been taken up by Australian-born New York-based landscape architect Julia Watson in her 2019 publication Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism. Questioning the continued dominance of what she calls “the mythology of technology,” Watson explores possible alternatives as found in more than 100 examples of indigenous land management practices from around the world.

While these case studies are extremely diverse in terms of location and approach, what they all have in common is the adoption of a symbiotic design process that aims to benefit both people and the ecological systems which they are part of and depend on. Early on in the book, Watson provides a name for this alternative technological vision – “Lo-TEK.” She states: “Extending the grounds of typical design, Lo-TEK is a movement that investigates lesser-known local technologies, traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), indigenous cultural practices and mythologies passed down as songs or stories.”

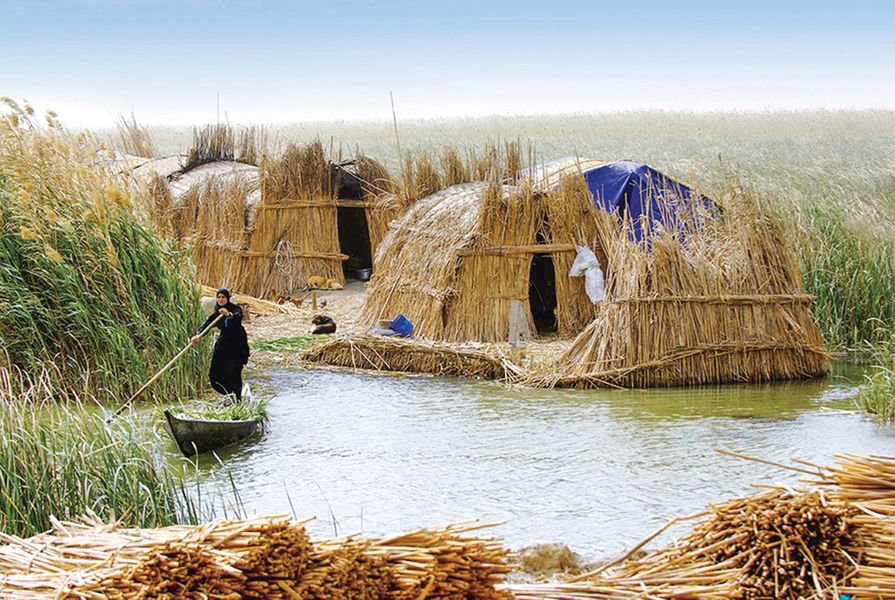

Built by the Tofinu people, the city of Ganvie on Lake Nokoué in southern Benin is ringed by a radiating reef system of 12,000 acadja fish pens.

Image: Iwan Baan

In this sense, Lo-TEK extends the traditional idea of “stewardship” as is often advocated for in landscape architectural practice, by integrating cultural practices such as storytelling and myth. These practices foster close connections to place over time, but have often been dismissed as irrational, primitive or superstitious by mainstream science. However new evidence has emerged that shows strong connections between indigenous knowledge passed down in stories and myths and scientific facts.1

In a deliberate subversion of the commonly used term “low-tech,” Watson describes indigenous technologies that are anything but simplistic. Instead, they represent site-specific and long-term solutions to various environmental challenges. The case studies in this book demonstrate that applied traditional ecological knowledge can be both highly productive and sustainable in the long term, at least at the local scale.

On the island of Bali, Indonesia, the Mahagiri rice terraces form part of a unique 1,000 year-old agrarian system known as the subak.

Image: David Lazar

One fascinating example is the living root bridges of the Khasi tribe in northern India, which for centuries have provided access between villages during times of flood. These bridges are not only stronger and better able to withstand monsoon floods than modern bridges, but they become more durable with time as the tree roots grow and expand into a tightly woven structure. Here is a case where traditional technology is clearly better than the modern version, being specifically adapted to its locale.

Another example can be found in the Mayan practice of milpa, which involves rotating annual crops on a 20-to-25-year successional cycle that begins and ends with a controlled slash-and-burn technique known as swidden. When considered alongside Australia’s bushfire crisis and the long-standing practices of Indigenous fire management in this country, it simply makes sense to stop and listen to those who have already developed an enduring understanding of country.

Watson certainly listens well, by foregrounding indigenous voices in a range of interviews within the book. However, the book’s broader proposal of adapting indigenous technologies for use within contemporary social contexts represents a much more complicated prospect. It is, for instance, worth noting the long histories of misinterpretation and appropriation that have characterized Western interactions with indigenous peoples. At the same time, the book emphasizes that what is really needed are new ways of thinking, of doing and of being in relation to the world. As Watson says: “Lo-TEK is a movement that prompts us to retrace our steps and reconsider the root of technological innovation.” In this sense, Lo-TEK is a book that advocates the human connection to land, above all else. It optimistically shows us how this has been done, and continues to be done, by people from all corners of the globe.

Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism develops a vision for a different type of technological design that is rooted in deep observation, dwelling in-place and careful listening to the accumulated wisdom of the original inhabitants of our lands. It is a timely publication for Australians, who are now facing unprecedented environmental challenges. This book sends an important message that enduring solutions to climate change can only grow out of a deep concern and love for country, as that which is inseparable from ourselves.

Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism. Julia Watson, Taschen, 2019.

1. Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident?, Magabala Books, 2014.

Source

Review

Published online: 3 Jun 2020

Words:

Emma Sheppard-Simms

Images:

David Lazar,

Esme Allen,

Iwan Baan

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2020