Landscape architects are in a good position to take action on climate change. There are two key actions to consider: climate change mitigation – reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which are the source of climate change; and climate change adaptation – adapting to the impacts that occur because of climate change (for example, longer periods of drought). Climate change actions in landscape architecture often focus on adaptation. However, adaptation without mitigation cannot be sustained, as adaptive efforts would need to constantly meet new benchmarks as the climate continues to change.1 For landscape architects to lead climate action, we need to actively engage with both adaptation and mitigation.

An important step for climate change mitigation is engagement with performance metrics through life cycle and metabolic thinking. Most design workflows do not include metabolic approaches and lack consideration of embodied GHGs across the process of creating built environments, including land-use changes and material manufacturing as well as operational GHGs emitted over the lifespan of projects, which have been proven to be significant. The sequestration capacity of urban trees, while important, is relatively insignificant compared to the embodied GHG emissions associated with manufacturing construction materials, urban furniture and paving, as well as changing land cover. For example, changing 10,000 square metres of land from native grassland to turf reduces the 50-year sequestration capacity by 66,000 kgCO2e – an amount equivalent to the GHG emissions of driving 360 cars from Melbourne to Sydney and back.2

Individual practices and initiatives pushing the boundaries for climate change mitigation are increasingly emerging across Australia. Landscape architects can have substantial impact across multiple scales of influence, including: (1) taking measures at the detailed design scale, (2) decision-making through masterplanning and (3) triggering change in urban policy and regulation. Here are three examples.

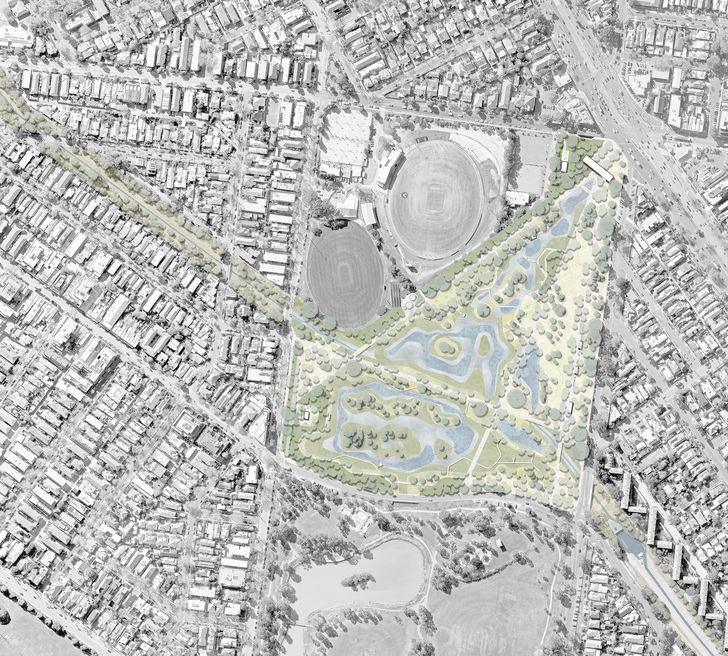

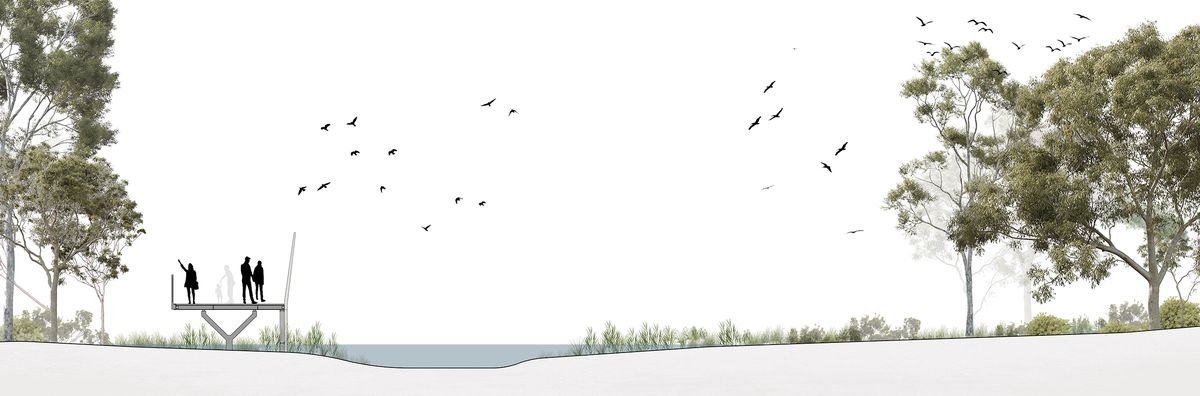

Elsternwick Park Nature Reserve Masterplan features wetlands, bird hides, a “chain of ponds,” woodlands, a “conservation island” and a look- out knoll. Image:

McGregor Coxall

In response to a lack of discipline-specific objectives for climate-responsive streetscape design and the absence of quantitative emissions data in landscape design, Libby Gallagher of Gallagher Studio has translated her ongoing research into practical design solutions. Through the development of multiple street design scenarios, the Beyond Green Streets project aims to evaluate the CO2 emissions and abatement potential for residential streets in Sydney. The project advocates for minimal design modifications in retrofitting existing streets and designing new streets. Simple treatments – such as adopting modest design changes, increasing tree canopy and minimizing paving – can lead to lower carbon footprints compared to standard street designs. The project helps designers experiment and identify optimum street configurations to meet mitigation and adaptation targets.

The transformation of a decommissioned golf course into Elsternwick Park Nature Reserve is an example of how ecological agendas can underpin decisions for climate change mitigation at the masterplanning level. Golf courses are often energy-intensive landscapes, embodying high GHG emissions due to required maintenance, including turf management, mowing, irrigation, fertilizer and machinery. The masterplan by McGregor Coxall addresses multiple challenges that can lead to better climate performance. Some of these interventions include re-using site materials (rock and felled trees) for furniture, accounting for the embodied energy of materials across their lifecycle, prioritizing recyclable materials, using permeable paving and passive irrigation, relying on off-line services such as composting toilets, and generating electricity onsite. When transforming golf courses into public spaces, it is important to preserve the environmental health of the roughs to maintain their biodiversity values and carbon sequestration capacities.

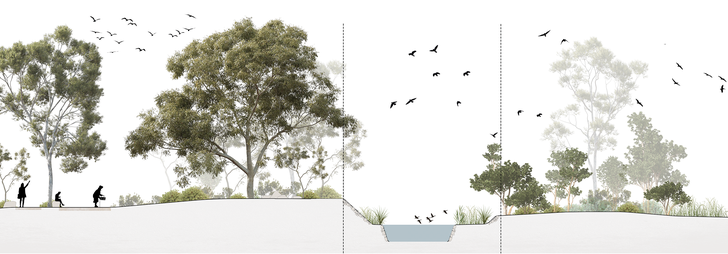

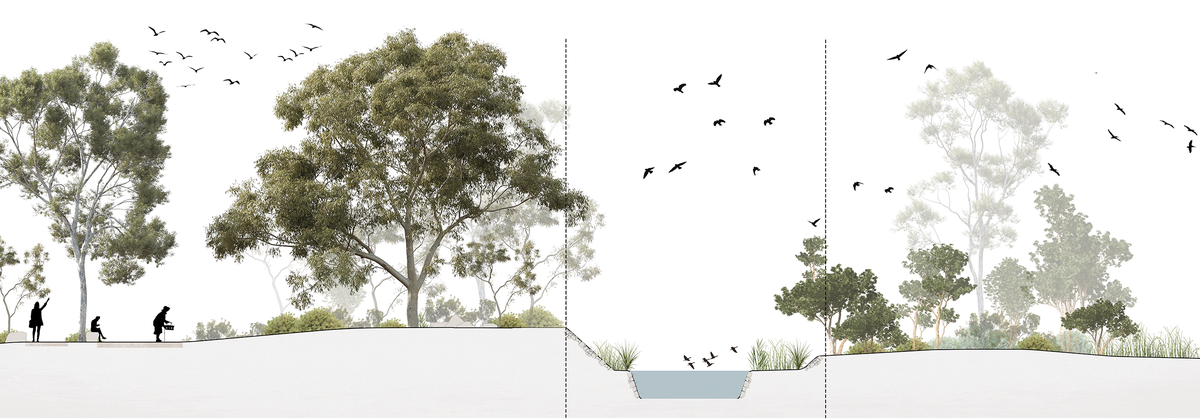

A cross-section through the “conservation island” from the masterplan for Elsternwick Nature Park Reserve shows a narrow water barrier with ha-ha walls. Image:

McGregor Coxall

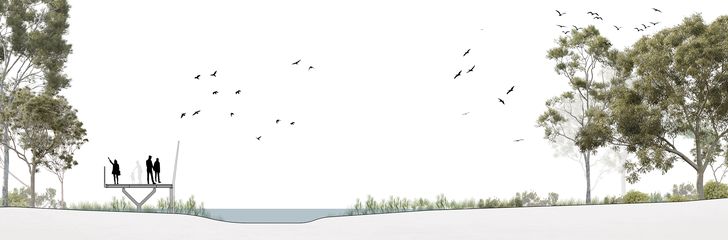

The masterplan for Elsternwick Nature Park includes bird hides, offering opportunities for visitors to learn more about waterbirds and local species. Image:

McGregor Coxall

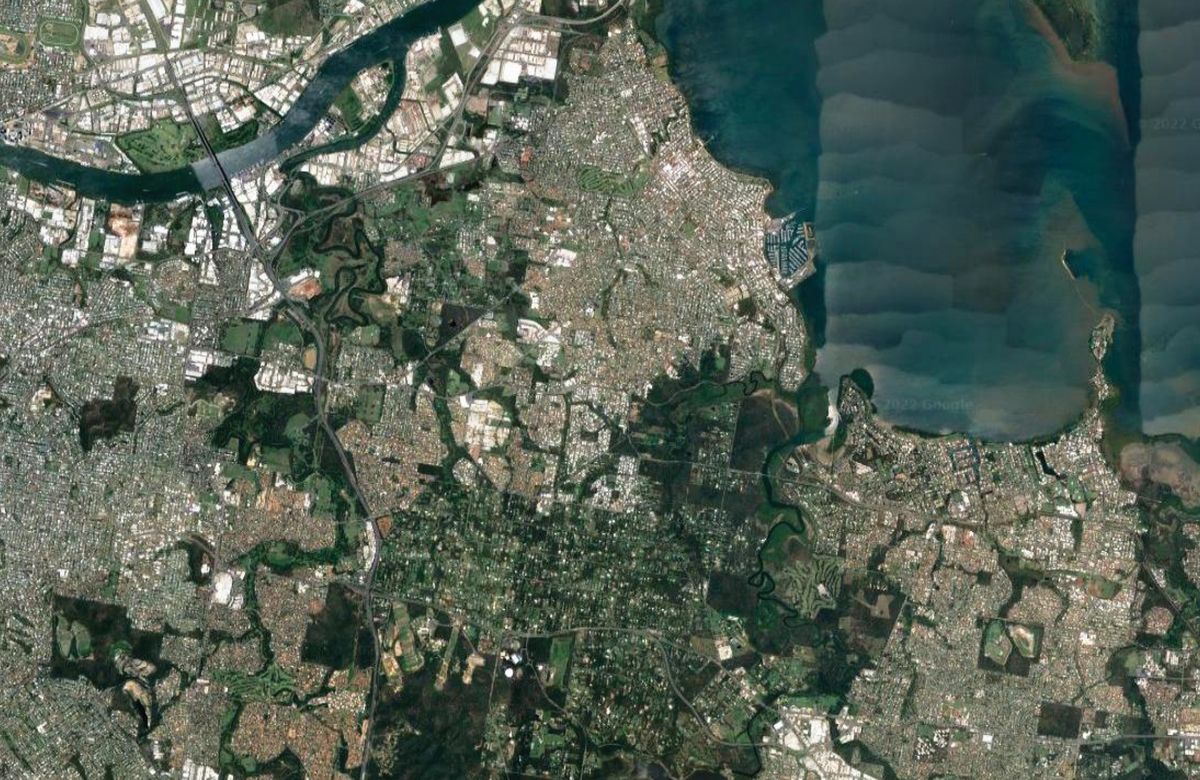

In 2021, the Victorian Planning Authority released new Precinct Structure Planning Guidelines that inform the development of new urban areas.3 The guidelines, developed with built environment professionals including landscape architects, specify a requirement for 30 percent canopy cover as part of wider efforts to provide cooler, greener urban areas – a key objective in the overarching metropolitan strategy Plan Melbourne.4 While a canopy cover target is an important element in driving climate action, successful tree establishment is dependent on factors spanning all stages of the creation and management of urban landscapes. Recent analysis of successful tree establishment in new precincts highlights the critical importance of spatial design, species selection, site preparation and maintenance. Ensuring there is sufficient space allocated for healthy canopy development requires, among a multitude of factors, attention to the design and layout of streets, subdivisions and underground services locations. Landscape architects have a vital role to play in these planning and design phases, as well as in the ongoing monitoring of tree establishment and health, which can inform future approaches to greening.

Voluntary tools have been developed to facilitate informed actions by enabling landscape architects and other built environment professionals to measure the carbon footprint of projects. Examples include the Environmental Performance Indicator tool5 (Sprout Studio, Sydney), the Green Factor tool (City of Melbourne) and the Climate Positive Design Pathfinder6 (Pamela Conrad, USA). The Pathfinder tool has been advocated for and adapted by AILA and has already been used by a number of Australian practices.

As a society, we must significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change to minimize social, ecological, and economic impacts. Landscape architects have the ability and responsibility to increase their agency in decision-making across all life stages of the built environment.7 Landscape architects need to have a stronger presence in planning and policy generation in order to push ecological and biodiversity agendas and disrupt business-as-usual approaches. Doing this requires an active engagement with science, politics, and climate advocacy.

1. Anna Hürlimann, Sareh Moosavi and Geoffrey Browne, “Climate change transformation: A definition and typology to guide decision making in urban environments,” Sustainable Cities and Society,

vol 70, 2021.

2. André Stephan et al, “Towards a multi-scale framework for modelling and improving the life cycle environmental performance of built stocks,” Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2022.

3. Victorian Planning Authority, “Precinct Structure Planning Guidelines,” VPA, vpa.vic.gov.au/project/psp-guidelines/p/key-ideas-review-of-guidelines/greener-and-cooler-environments (accessed 18 February 2022).

4. State of Victoria, “Outcome 6: Melbourne is a sustainable and resilient city,” Plan Melbourne, planmelbourne.vic.gov.au/highlights/a-sustainable-environment-resilient-to-climate-change (accessed 18 February 2022).

5. Sprout Studio, “Environmental Performance Indicator,” Sprout Studio website, sproutstudio.com.au/research-innovation-epi-tool (accessed 18 February 2022).

6. Climate Positive Design, “Pathfinder,” Climate Positive Design website, climatepositivedesign.com/pathfinder (accessed 18 February 2022).

7. Anna Hürlimann et al, “Towards the transformation of cities: A built environment process map to identify the role of key sectors and actors in producing the built environment across life stages,” Cities, 2021.

Source

Practice

Published online: 24 Jun 2022

Words:

Sareh Moosavi,

Anna Hurlimann,

Judy Bush

Images:

Andrew Gook/Unsplash,

Google Maps,

McGregor Coxall,

Szabolcs Toth/Unsplash

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2022