The opening weekend for Colony: Australia 1770–1861 and Colony: Frontier Wars begins with a Welcome to Country in the foyer of the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia in Federation Square. Arweet Carolyn Briggs of the Boon Wurrung Foundation stands at the lectern, eucalyptus bough in hand, and tells the audience that “Wominjeka” means not only welcome, but to come: “Ask to come and what is your purpose in coming?” This is a salient question to carry as a reminder for those attendees encountering the exhibition ahead.

John Lewin, The gigantic lyllie of New South Wales, 1810. Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Purchased, 1968.

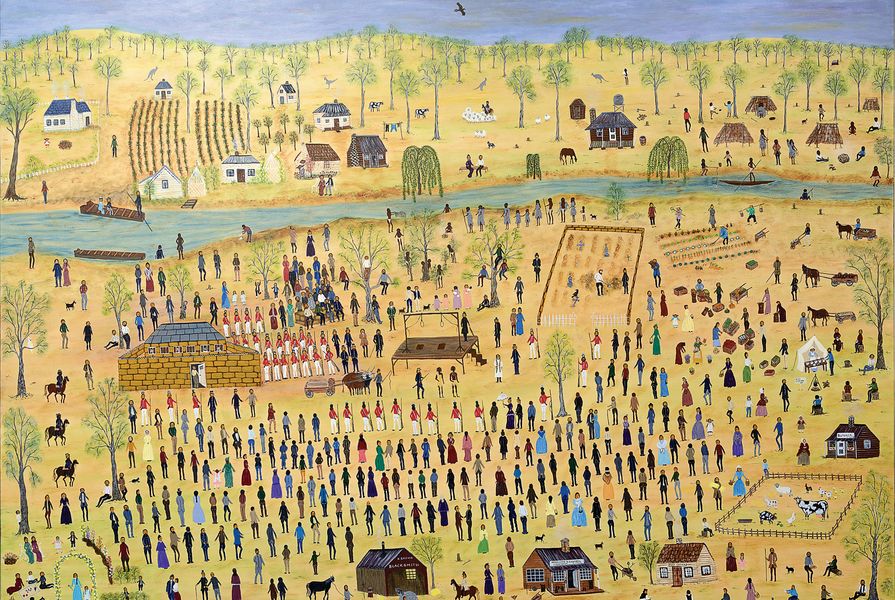

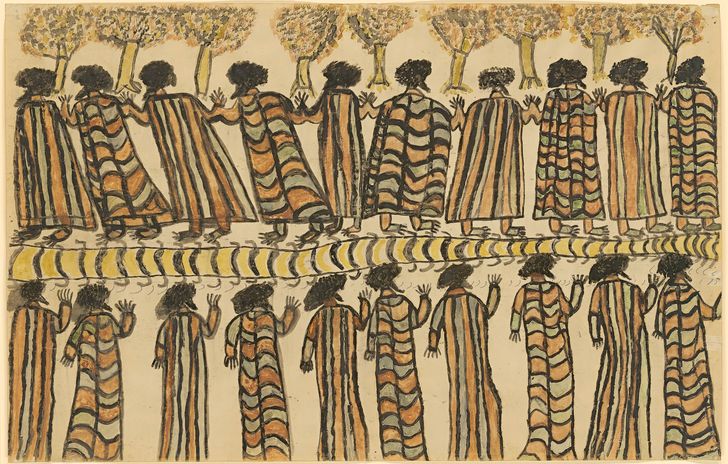

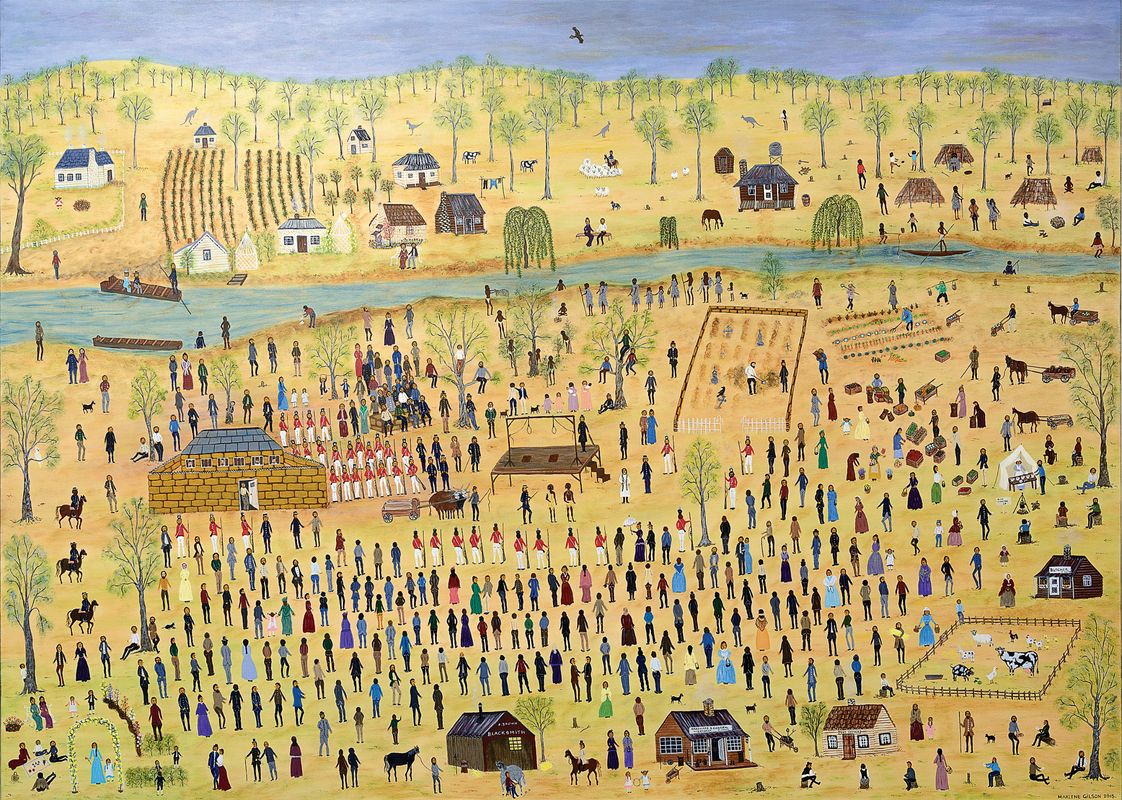

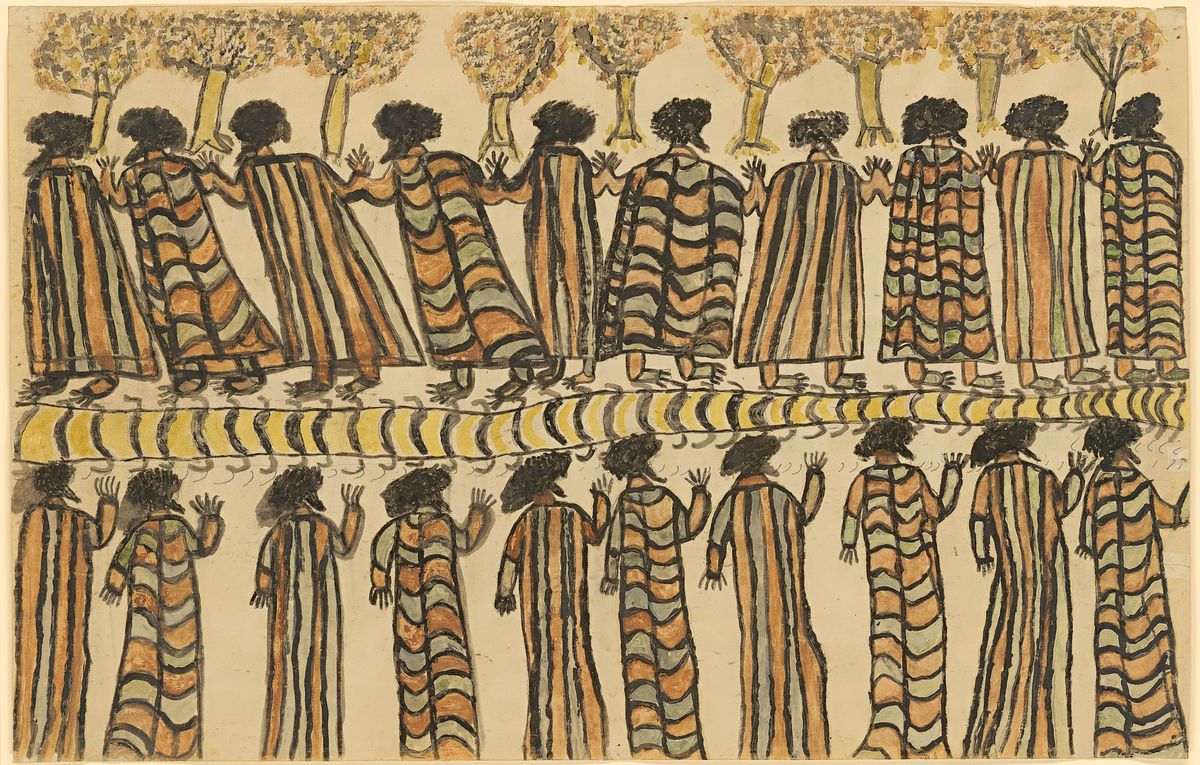

The second part, Colony: Frontier Wars, is both a lament and a call to action. This selection of works by primarily Indigenous artists is grouped not by time, but by words: Terra Nullius, Stolen, Lament, Absence, Desecration and Presence. These powerful refrains offer an alternative viewpoint, proclaiming both the devastating effects of the colonial project and the resilience of the First Peoples in retaining culture and community. A highlight of this section of the exhibition is the extensive examples of William Barak and Tommy McRae drawings. In Colony: Frontier Wars, a redress of colonial erasure is enacted. Historic objects previously attributed in the museum convention as “Unknown” become “Once Known.”

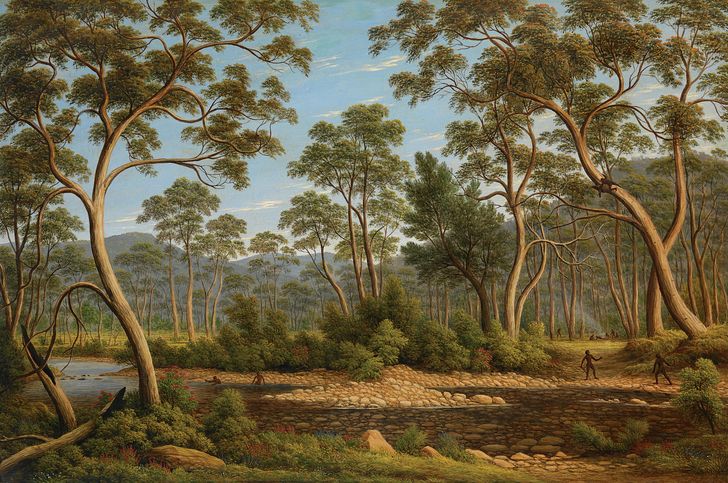

John Glover, The River Nile, Van Diemen’s Land, from Mr Glover’s farm, 1837. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest, 1956

By presenting two exhibitions in counterpoint the curators’ intention is to remove the centrality of the European view. This could be described through the metaphor of a stereoscope, a device that merges two viewpoints to create another encompassing image. With different images speaking together or against one another at the same time, a tension between opposing perspectives is constructed. The dialogue provides nuanced feedback that allows the viewer to visit and revisit the meaning and nature of the works.

Take, for instance, the recurring image of the shield as a symbol of both resistance and conflict. In the first powerful display in the Colony: Australia 1770–1861 exhibit, one encounters a mounted line of nineteenth-century parrying and broad shields, swirling with exquisite carvings testament to the skills of the unrecorded makers. However, in a subsequent display that illustrates the new territories being drawn into being through the evolution of coastline mapping, one of the earliest portrayals of Indigenous people shows shields in another context. The Thomas Chambers print, Two of the Natives of New Holland, Advancing to Combat (1773), shows first contact in Botany Bay on 28 April 1770, with two Indigenous men depicted in classical poses brandishing the same aforementioned shields. The print’s inscription reads, “Our people fired again and wounded one of them …We endeavoured to pacify them, but to no purpose … After looking about us a while we left … taking with us their weapons.” The viewer is compelled to reconsider that mounted line of shields and speculate on their provenance.

Brook Andrew, Australia, born 1970. The Island IV, 2008, from The Island series. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Gift of Michael Schwarz and David Clouston through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 2017. © Brook Andrew.

Shields are also present in Colony: Frontier Wars, but in Steaphan Paton’s artwork Cloaked combat and video Cloaked combat #2 (2013) they are under attack by modern weaponry, exposing the role technology plays in cultural collisions. A projection of the artist dressed in camouflage fires arrow after arrow with a high-tech crossbow – each thwack of an arrow landing is deeply unsettling.

The interweaving of two viewpoints is again provided by the Natural History display in the Colony: Frontier Wars exhibit: a wondrous presentation of botanical and natural illustrations, mounted specimens and cases dedicated to tracing how the poses of two of Australia’s most recognizable animals, the kangaroo and black swan, were first recorded and echoed through the decorative arts for the next century. But the inclusion of Sarah Stone’s watercolour Perspective [interior] view of Sir Ashton Lever’s Museum (1785) gives us a glimpse of a different story, reminding us where all these natural treasures were ultimately bound. Another very subtle and poignant juxtaposition is provided by a case of colonial needlework samples prepared by colonial women and Queen’s Orphan School orphans placed adjacent to a display of beautiful maireener shell necklaces and a woven basket by Fanny Cochrane Smith, a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman, drawing cross-cultural parallels in the tradition of women passing down crafts over generations.

William Barak, Wurundjeri, c. 1824–1903, Figures in possum skin cloaks, 1898. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased, 1962.

In another feedback loop consider the Dixson collector’s chest (1818–20) vis-a-vis Brook Andrew’s Vox: Beyond Tasmania (2013) , both cabinets of curiosities that say something about the nature of collecting trophies. The first, an example of nineteenth-century Enlightenment interests with a superb display of natural history specimens; the second, a subversion of the type – a cabinet that speaks to the ethnic stereotyping and desecration of Aboriginal burial sites. Its contents feature an array of disassembled skeletons, scientific artefacts, repellent anthropological literature and ethnic images.

The spatial separation of the two exhibitions, Colony: Australia 1770–1861 on the first floor and Colony: Frontier Wars on the third, perhaps works against a seamless dialogue between the two narratives, but the overall message remains powerful: that to approach a new and inclusive idea of Australian identity we must move forward with both eyes open.

Colony: Australia 1770–1861 ran from 15 March – 15 July, and Colony: Frontier Wars from 15 March – 2 September at the NGV Australia Federation Square.

Source

Review

Published online: 5 Sep 2018

Words:

Cassandra Chilton

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2018