Jock Gilbert and the RMIT Landscape Architecture program have been building a relationship with Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation (CMAC) through projects on Culpra Station since 2014. The projects arise from this relationship and aim to address the corporation’s vision of facilitating culturally appropriate enterprise opportunities for Aboriginal people through engagement with Country on Culpra. In their work, CMAC and RMIT have focused on the design of infrastructure to support two strands of enterprise alongside agriculture: cultural education and tourism.

In mid-2021, the NSW Department of Environment and Heritage, Local Land Services Western Division commissioned Charles Massy and RMIT to produce a report outlining strategic approaches to culturally, environmentally and economically appropriate land management in support of a range of enterprises.

The project team spent four days on Culpra Station in late June 2021, hearing stories, walking Country, sharing meals, and observing and reading landscape. Drawing upon this research, in addition to eight years of previous work, the resulting report identified a suite of interrelated enterprise opportunities and outlined strategic approaches toward the design and development of infrastructure to facilitate these. From both a regenerative and a cultural perspective, the report also identified ways that such enterprises might strengthen and enrich land management objectives and outcomes – in recognition that the design of enterprise, infrastructure and land management are intrinsically interrelated.

The project proposal that most clearly manifests these connections is the Boomerang Billabong Rehydration Project (BBRP), an infrastructure project conceptualized through story. With clear regenerative environmental land management outcomes, the BBRP provides a platform for culturally appropriate enterprises based on education and tourism. Importantly, as members of the BBRP project team, we think the project also provides learnings for the profession around how, by beginning with Country through story and culture, landscape architecture can work productively and generatively with related knowledge systems and through design to produce holistic and meaningful outcomes. We have come to the project with different skills and areas of expertise, driven by Country through reconciliation. While this is ostensibly a multi-layered landscape project, we draw on traditional cultural knowledge; contemporary Indigenous experience, including self-determined enterprise development; ecological regenerative principles; and design advocacy. BBRP is a project of design as reconciliation; we are learning as a team through being on Country, yarning, sharing and listening.

Despite suffering from degradation over generations, Culpra Station remains a breathtaking landscape of mallee, black soil floodplains and riverine forest.

Image: Sophia Pearce

Sophia Pearce – Nyi Kirree Kira Kulyparana Barkandji Goomagooli, Wurtoo, Nhuugha, Marley, Moorpi (Hello and welcome to our Country, my Country, Kulpra, Barkandji land).

The birth of Billilia (butterfly)

Long, long time ago, the animals could talk to humans and to each other; they had no knowledge of death. All through the summer months, it was the custom of all tribes, animals, reptiles and birds to gather on the Milli (Murray River). The wise old men of the tribes would sit around and talk, while the young people played sports and hunted.

One day a young cockatoo fell out of the tree and broke his neck. The animals touched him with their spears, but he could not feel; they opened his eyes, but he could not see. The animals were completely mystified because they knew nothing of death. Then all the medicine men tried to awaken the cockatoo but without success.

A general meeting was called to discuss the matter of the dead bird. Many spoke but could not solve the mystery. Although he was very wicked, Waakuu the Crow was asked to speak as he was also known for his great knowledge. He stepped forward, took up his wit wit (short, feathered medicinal spear) and threw it into the river. The weapon sank and gradually rose again to the surface.

“There,” said Waakuu, “is the great mystery explained. We all go through another world of experience and then return. Who will volunteer to go through this experience and test whether it is possible to return?”

“We will,” said the different bugs and caterpillars. “We will return in another form at springtime during the year and we will meet you in the mountains.”

As the stars indicated the drawing near of the following spring and the waters began to flow, the animals, birds and reptiles gathered in the mountains to await the great event. The dragonflies, the gnats and the fireflies came around the campfires as heralds of the wonderful pageant that was to take place. Already the trees, the shrubs and the flowers had consented to lend themselves for the occasion. The wattle put forth all its wonderful yellow and the waratah its brilliant red, and all the other flowers showed their blossoms of various colours.

As the sun rose, the dragonflies came up through the entrance of the mountains heading an array of butterflies, each species and colour in order. First, the yellow came and showed themselves. They flew about and rested on the trees and flowers. Then came the red, the blue, the green, right on through all the families.

The animals that had gathered were delighted. They gave great cries of admiration. The birds were so pleased that, for the first time, they broke out in song. Everything looked its best. When the first butterflies had landed, they asked the great gathering: “Have we solved the mystery of death? Have we returned in another form?” And all nature answered back: “You have.”1

This story belongs to the Barkandji people, as it always has.

The project team standing in the site of proposed Boomerang Billabong on Culpra Station.

Image: Tom Flugge and Albert Rex

Jock Gilbert – Culpra Station is a property owned and managed by the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation (CMAC), and is located approximately 50 kilometres south-east of Gol Gol and 42 kilometres north-west of Euston, New South Wales. It straddles the Murray River to the Victorian border. Prior to CMAC ownership and management, infrastructure on the property had suffered degradation over the course of several generations, leaving the conduct of enterprise on the property difficult. The environmental, landscape and cultural attributes of the property are significant; cultural sites and artefacts, including scar trees, burials, fire hearths and ancient fish traps sit next to abandoned pastoral infrastructure, all within a breathtaking landscape of mallee, black soil floodplains and riverine forest. Drawing on these attributes, CMAC and RMIT have been working toward the development of agricultural, silvicultural and tourism-related enterprises which can assist in providing a self-determined future for CMAC and the broader Aboriginal community of the area, as well as educative and collaborative opportunities, through projects, for non-Indigenous designers and practitioners. This is reconciliation.

Charles Massy –The semi-arid landscape of Culpra is fragile and was rapidly altered and degraded upon the first incursions of European squatters and their livestock that began in the 1840s. The appearance and function of the Lower Murray–Lower Darling river systems in the Culpra Station region today would be unrecognizable to the Indigenous landowners of the 1840s due to the extent of the modifications, degradation and simplification. This degradation of the landscape intensified from the 1870s, driven by a prevailing belief that technology was the only limitation to pastoral profits. The effects of massive overstocking of the land with cattle and sheep were subsequently exacerbated by a disastrous invasion by rabbits in the region from the 1860s.2 With the arrival of successive droughts in the 1880s – particularly the six-year Federation Drought, beginning in 1896 – environmental damage to the area began to reach catastrophic proportions. The 1960s saw this destruction further exacerbated, as precious water from the Murray River began to be used for agricultural irrigation, a situation culminating today in the explosion of irrigated but thirsty crops, including cotton, rice and now almonds. As noted by Murray–Darling Basin historian Quentin Beresford, European development in the Murray–Darling Basin has “brought the ecosystem of large parts of the Basin almost to its knees.”3

The vitality of the Culpra landscape, and the biodiversity it supports, relies on recharge through flooding.

Image: Sophia Pearce

Culpra Station is an 8,500-hectare rural New South Wales property previously used for cropping and grazing. It is home to a number of significant Aboriginal cultural heritage sites.

Image: Tom Flugge and Albert Rex, Google Satellite.

Jock Gilbert – While fragile, the landscape of Culpra remains spectacular, situated among riverine forests of tall river red gums, black soil floodplains and rolling red sand dunes. These floodplains, riverine wetlands, billabongs and small creeks support an abundance of rare and endangered birds and other wildlife, and buzz with life after rain. The vitality of the landscape relies on recharge through flooding – ephemeral natural events through which billabongs, creeks and flood-runners are regularly filled with water, their courses often pushing uphill through pressure from the river. Over the years, landscape management, commodification of water and control of the Murray–Darling Basin has left the landscape systems of Culpra (and beyond) depleted of the water that is vital to their health. Now, the billabongs are too often dry, the flood-runners inactive.

Charles Massy – In a healthy state in long co-evolved grasslands, shrublands and forests, solar energy drives the system. Via photosynthesis, captured sunlight inputs sugars into the soil to feed the soil biology and lay down soil organic carbon. This in turn has a major positive impact on the capacity to store and use water. Together, these three functions impact the area’s biodiversity: the integrated, interactive function of above-ground vegetation with the underground components creates long, co-evolved functional biodiversity – plants, animals, birds, insects, soil microbiology, and so on. Through engagement with Country, the BBRP seeks to both regenerate some of the landscape’s natural functionality and re-instigate some of the river’s natural functionality by encouraging more water to be stored in the river’s systems. This, in turn, would flow on to have a positive effect on how the region’s biodiversity operates.

Jock Gilbert –Place-based learning scholar Margaret Somerville describes Country as “… not place, but nor is it nature or environment. There is no separation of human activity and the natural world … Country never loses the sense that the original creation story is still always there, in the meaning of that particular location, in the shapes of the land, in its ongoing stories … ”.4 Alison Page quotes Indigenous researcher Danièle Hromek’s wonderful definition of Country, which is both poetic and pragmatic: “Country soars high into the atmosphere, deep into the planet crust and far into the oceans … incorporating both the tangible and the intangible … Caring for Country is not only caring for land, it is caring for themselves/ourselves.” Page takes this further, noting; “Just as trees, mountains and rivers contain stories, the design of new places, objects and systems can be a purposeful extension of Country and imbue meaning and story into them, so that as we engage with them over time, multiple narratives are strengthened.”5

For Uncle Barry Pearce, Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation chair, “that river [the Milli] runs through my veins, it’s a life-blood to my people.”6 Country provides a way of understanding the significance of Culpra Station and the myriad interwoven social, environmental and cultural networks in and of which it is constituted. The BBRP draws on the story of Billilia and aims to bring Country to life by providing opportunities in the present and actively supporting the future. It expresses and reinforces the traditional story of Billilia while aiming to provide employment and training opportunities for community members, firstly in the stages of the project’s inception, construction and maintenance, and then in an ongoing way through cultural tourism and education supported by the formation of a tourism enterprise.

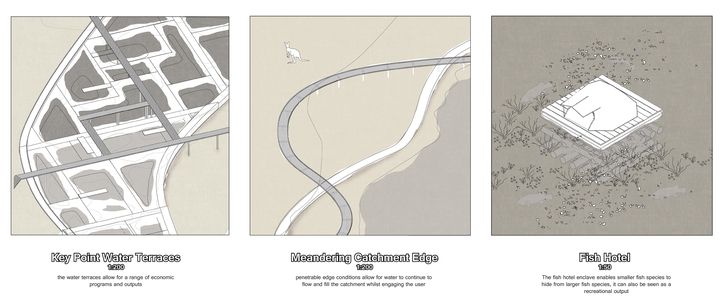

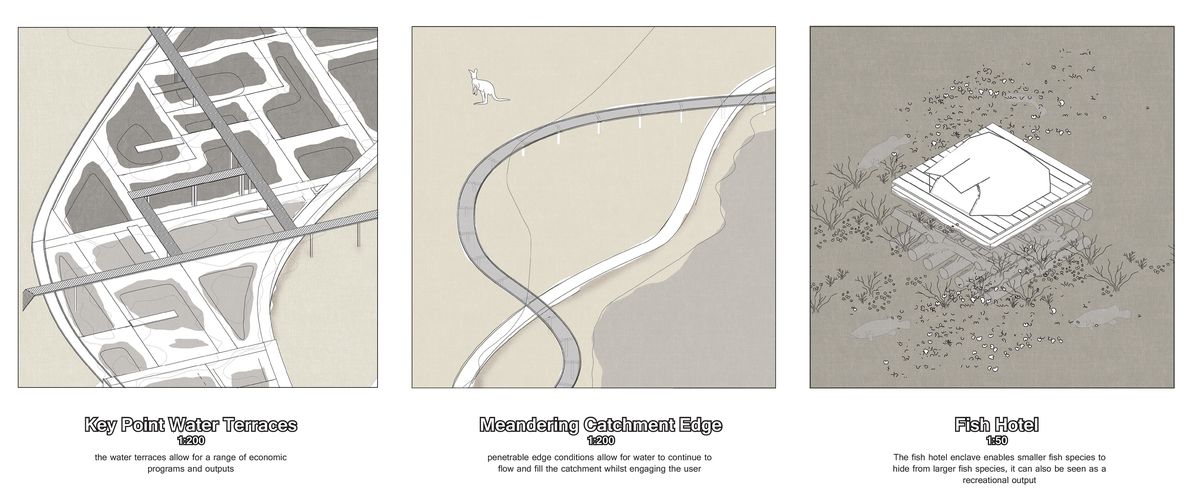

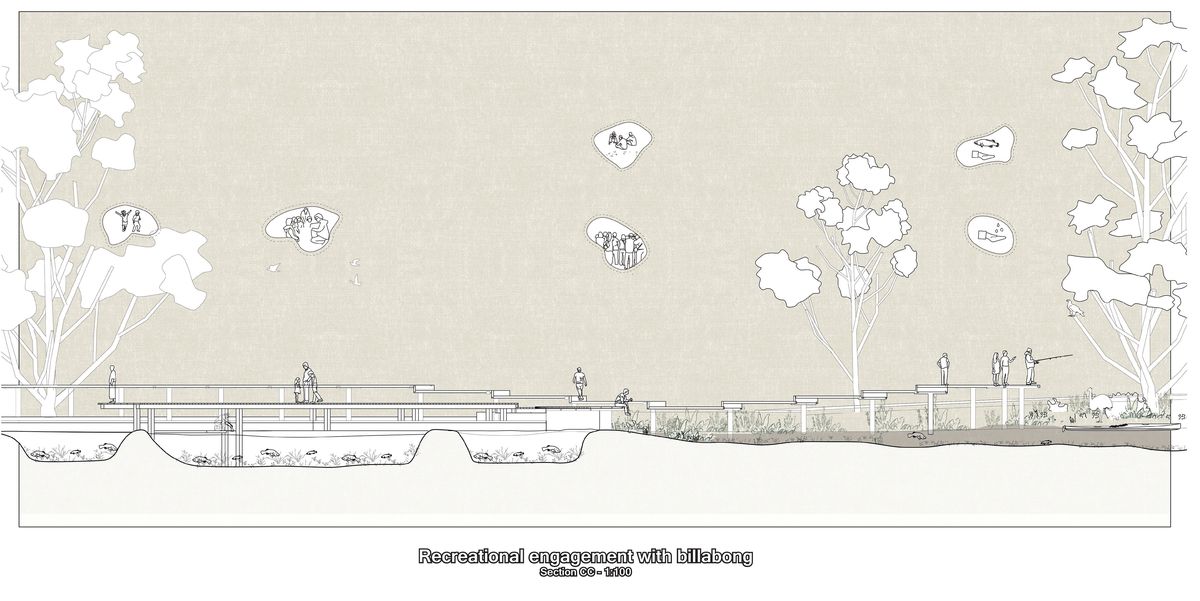

Drawings depicting, from left to right, the water terraces, a meandering catchment edge and a “fish hotel” enclave, where smaller fish species can hide from larger fish.

Image: Tom Flugge

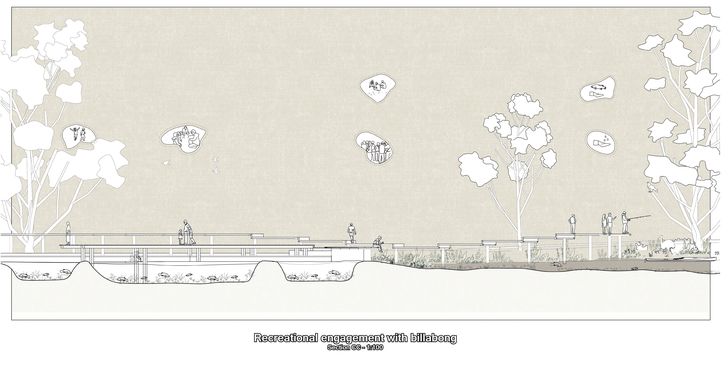

Section through the design showing recreational engagement with the billabong.

Image: Tom Flugge

Albert Rex– Reconciliation is an urgent issue to be addressed by the profession of landscape architecture. Addressing it will require both individual and institutional action. For non-Indigenous practitioners, this will involve a move beyond those often invoked protective mechanisms of expertise, cynicism, problematization, deficit models and defeatist despair (the familiar refrain of “it’s just too hard”) and into shared relationships with Indigenous knowledge on the terms of its custodians and holders. The profession itself must also take ownership of and responsibility for the fact that it continues to participate in and benefit from colonial and neo-liberal processes of wealth extraction from, and capital production on, violently stolen land, supported by Commonwealth, state and local governance regimes of land and property management.

Along with other privileged professional bodies that work with managing and modifying land, landscape architecture as a profession is clearly part of the problem. However, the discipline has the potential to make significant contributions – our knowledge, as well as the power derived from it, must be turned toward processes of reconciliation – engaging in, with and through Indigenous-led processes of Caring for Country.

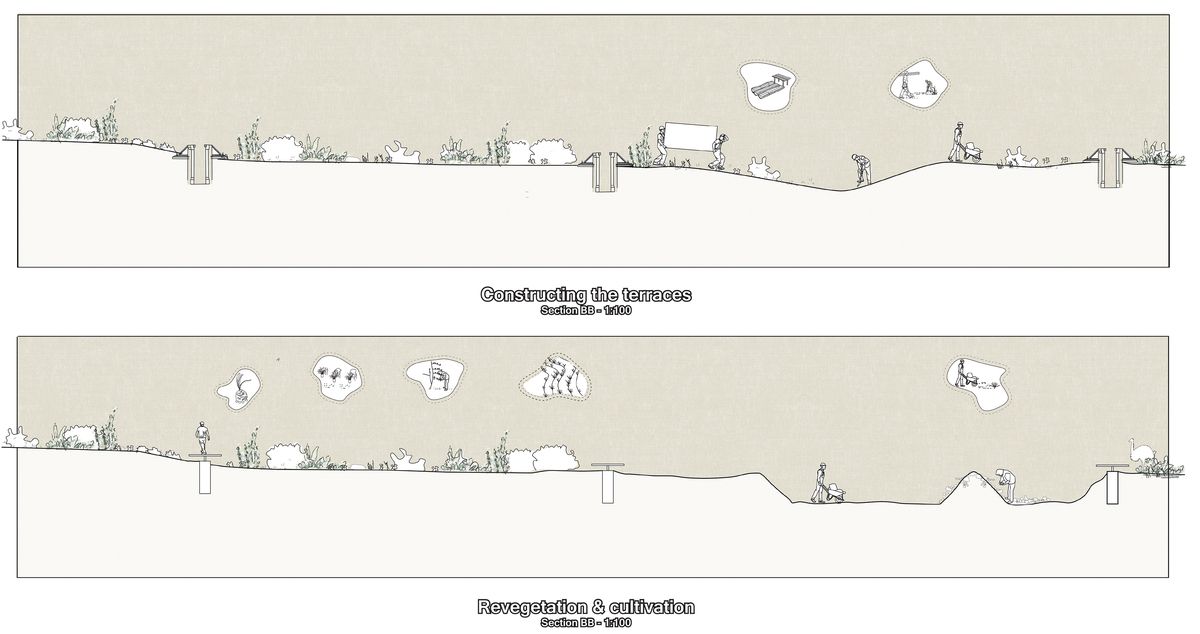

Tom Flugge – As a multi-functional and regenerative extension of Kiira-Kiira (Sophia’s Barkandji Country), the project embodies and enacts the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation’s vision for building a sustainable economic land base for local Aboriginal people. It leverages the securing of nguku (cultural water) from the Milli as the catalyst for regenerating an ephemeral billabong as a semi-permanent, cyclical nguku body at Culpra Station.

The design will take the form of a series of site-responsive, submerged, organic nguku terraces, paddocks and paths constructed along the river’s edge from locally sourced marnti (clay) rocks, gravel and salvaged red gum timber. The terraces will provide opportunities for the re-establishment of ephemeral aquatic habitat and ecology through the selection and planting of culturally and ecologically significant endemic species, which will offer habitat, food and protection for endangered native fish species such as the parntu (Murray cod) in times of drought and/or fish kill events – a “fish hotel” for selected species. The restored cyclical inundation of the billabong and its constructed terraces will support the breeding of native fish species with concomitant increases in biodiversity, while rejuvenating the small-water cycle in its immediate vicinity. This will provide opportunities for phyto-remediation and the establishment of native bush foods in surrounding paddocks. This, in turn, will provide opportunities for further establishment of enterprise and employment for community members through the harvesting and marketing of cultural foods, educational tourism, and the establishment of a ranger and guide program.

The BBRP positions itself within Indigenous knowledge systems and community values. It embodies a reciprocal relationship between people, animals, land and water, Country and kin, songlines and the future. Here we can see the ecological importance of nguku inundating the constructed marnti (clay) terraces at Culpra Station. We can begin to understand the story of Billilia manifesting in life and rebirth through the regeneration of Kiira-Kiira at Culpra Station.

1. This is the shortened version of a story I learnt from my grandmother and, to a larger extent, my mother. My kanyita worked on her Country as an indentured domestic servant and her husband worked as head stockman on Billilia Station in western New South Wales. For the full story, you are welcome to visit with us at Culpra Station. I share this story on behalf of my family, the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation, all Barkandji people, their ancestors and elders, as well those emerging.

2. Charles Massy, The Australian Merino (Melbourne: Viking O’Neil, 1990).

3. Quentin Beresford, Wounded Country: The Murray–Darling Basin, A Contested History (Sydney: New South Publishing, 2021).

4. Sophia Pearce and Jock Gilbert, ‘The Landscape of Country’, Landscape Architecture Australia, Issue 162, May 2019, pages 17–19.

5. Alison Page, Paul Memmott, Margo Neale (eds), Design: Building on Country (Melbourne: Thames and Hudson, 2021).6.Jock Gilbert and Christine Phillips, ‘Respecting Country – A New Australian Design Approach’, Landscape Australia, 16 July 2021, landscapeaustralia.com/articles/design-building-on-country (accessed 1 December 2021).

6. Personal communications.

Source

Practice

Published online: 26 Apr 2022

Words:

Jock Gilbert,

Sophia Pearce,

Charles Massey,

Albert Rex,

Tom Flugge,

Uncle Barry Pearce

Images:

Sophia Pearce,

Tom Flugge,

Tom Flugge and Albert Rex,

Tom Flugge and Albert Rex, Google Satellite.

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2022