Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this article contains images and names of deceased persons.

The chatter and laughter of several hundred people, all overjoyed to be out at a gala dinner after a long season of COVID in Melbourne, quietens as Wurundjeri Elder Aunty Di Kerr takes to the stage. She begins by asking us to look up at the Leonard French stained-glass ceiling above our heads in the Great Hall at the National Gallery of Victoria. She loves this ceiling, she says, because the mosaic of coloured, fragmented glass of different shapes and sizes is an eloquent metaphor for community, where multiplicity and difference is essential for making the whole. She intones an extensive list of Elders and others she wishes to honour before the evening’s events can proceed, and concludes by extending her hand of friendship, so we can continue together on the journey of healing people and Country. Relationships of care, rather than hierarchies of power, are at the heart of Indigenous culture and law.

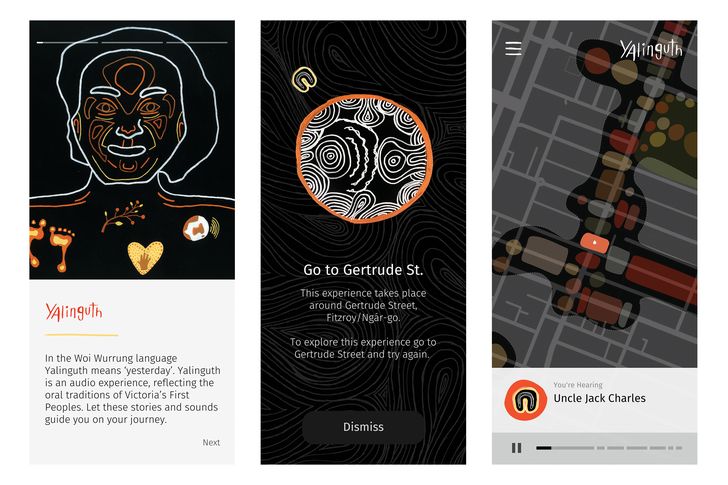

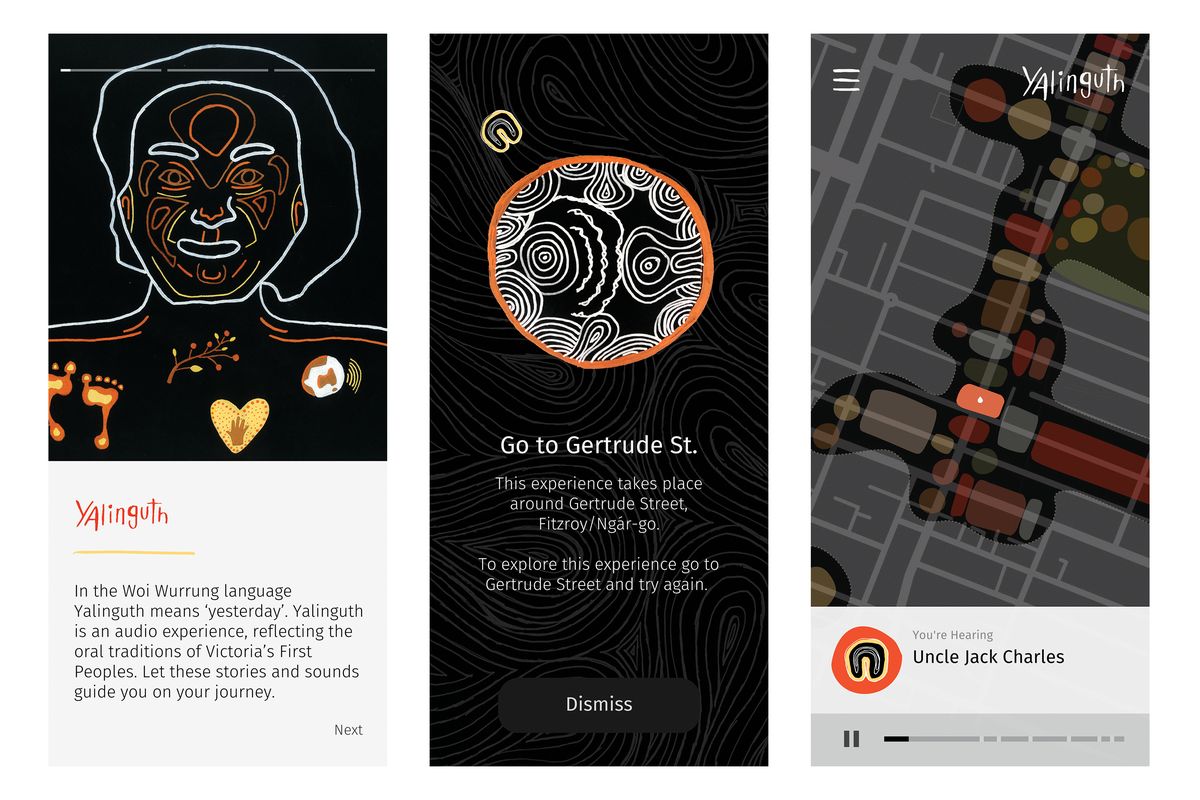

Screenshots of the Yalinguth mobile app. The design team took great care with the interface, aiming for “clear, direct and friendly” graphics. All icons were made by Aboriginal artists.

Image: Yalinguth

It was a fitting way to begin the 2021 Victorian Premier’s Design Awards presentation, held during Melbourne Design Week on 24 March 2022, at which a project developed by a team that included the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation received a High Commendation. Yalinguth – meaning “yesterday” in Woi Wurrung – is a First Nations, immersive, geo-located, audio story app that shares recollections of Gertrude Street, Ngár-go (Fitzroy) by 36 Elders whose lives have intersected with this urban landscape. The stories were recorded by 20 of their grandchildren, nieces and nephews at ad hoc community recording studios set up at MAYSAR (Melbourne Aboriginal Youth Sport and Recreation Co-Operative) on the strip since 2019. Yalinguth recounts personal memories of life in the suburb, a significant centre of ferment and protest for the Aboriginal rights movement in Melbourne. In contrast to many urban landscape projects that showcase traditional Aboriginal environmental knowledge, this project tells social and political stories of the impact of invasion and resistance to settler colonization.

The emplaced, polyphonic history is simultaneously warm, intimate, funny, sad, haunting and beautiful, largely as a result of the process of co-authorship and the pace of development and production. The Yalinguth working group of 12, from six organizations, began developing the project seven years ago. Three of the organizations are Aboriginal-led: Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation (Uncle Colin Hunter and Charley Woolmore); Yarnin’ Pictures (Uncle Bobby Nicholls and Rebecca McLean); and the Melbourne Community Indigenous Film Collective (Uncle Robbie Bundle). The other partners are Storyscape (Pip Chandler and Zoë Dawkins); RMIT digital design and animation academics Chris Barker, Max Piantoni and Kate Cawley; and Melbourne School of Design architecture and landscape architecture academics Janet McGaw – author of this article – and Jillian Walliss – guest editor of this special issue of Landscape Architecture Australia . None of us could have developed the project alone. Like the fragments of glass above our heads, all 12 of us played different parts in constructing the puzzle of this narrative landscape.

Uncle Bobby Nicholls (far R) shares stories with a group of listeners gathered on Gertrude Street in 2019.

Image: Pip Chandler

So, how was such a complex array of authors assembled to create one app? Successful engagement between Indigenous communities and design teams requires three key elements: time to develop trust, share ideas and follow appropriate protocols for approval before decisions are made; money to pay First Nations participants for their time and cultural knowledge; and processes that lean toward self-determination wherever possible. Yalinguth has been in development for around eight years, but it was an alliance born out of previous partnerships, some of which date back more than a decade. The dance was slow at first, while we narrowed down a site, participants and the stories people wanted to share. We were fortunate to receive pilot funding from the University of Melbourne to kick things off. This was followed by a $300,000 philanthropic grant with no strings attached – a rare gift. A subsequent large Creative Victoria grant plugged the holes, enabling the project to move from proof of concept to fully functioning app. Finally, each of us has known when to lean in to provide support with knowledge, expertise, or plain hard work, and when to disappear. Sometimes, the most important design work is simply to set up a process.

Uncle Bobby, Uncle Colin, Uncle Robbie, Aunty Denise McGuinness and Aunty Rieo Ellis gathered the community, while Storyscape took the lead in developing the methods for equipping First Nations participants to tell and record their Ngár-go (Fitzroy) stories themselves. Storyscape is an arts, community and advocacy partnership established by Zöe Dawkins and Pip Chandler. Pip and Zöe drew on their expertise in community arts, filmmaking and media production to devise creative, skill-building, community workshops where the uncles and aunties gathered to yarn, and young people were trained to make high-quality recordings. The warmth and intimacy of the stories in the app are a testament to the process. Storyscape also devised and ran design competitions for the visuals, open to First Nations artists. The work of the winning artists, Larna Massari and Graham “BJ” Braybon, has been used in the logo, app visuals, posters and footpath stencils. The community’s sense of pride and ownership has grown with every event, from the trial run of the app in December 2020, through the soft launch demanded by COVID lockdowns in 2021 to the NAIDOC week storytelling at the Builders Arms Hotel and the official launch at Atherton Gardens during the Gertrude Street projection Festival in July 2022. The enthusiasm with which it has been received by the larger community has been overwhelming, evidenced by the vast traffic through the socials, international coverage in the global Atlas of the Future1 and prime-time news coverage after the launch alongside the Garma Festival of Traditional Cultures.

From left to right: Graham “BJ” Braybon, the late Uncle Jack Charles and Uncle Graham “Bootsie” Thorpe

Image: Chris Hopkins/The Age

The app invites listeners to consider an intricate web of relationships between places, people, stories and moments in time.

Image: Pip Chandler

It is still rare for this triumvirate of time, money and partnerships that evolve into community ownership to align in built environment design projects. Typically, deadlines loom large, dollars are tight and First Nations groups may be stakeholders or users, but the paying clients are more often than not local or state government departments or non-Indigenous landowners. But take a moment to reconsider. There are an ever-growing number of policies and Reconciliation Action Plans that articulate statements of commitment by organizations to support better partnerships with First Nations stakeholders, particularly on projects in the public realm. Landscape architects working in public space design can leverage these to be better allies, ensuring policies don’t remain empty rhetoric, lost on websites or forgotten by staff. Yalinguth shows how truth-telling can start right now in the public sphere, if designers follow community interests and lend their creative and technical expertise to First Nations communities so they can share their own stories on their own terms.

1. See Atlas of the Future website, atlasofthefuture.org/project/yalinguth (accessed 17 August 2022).