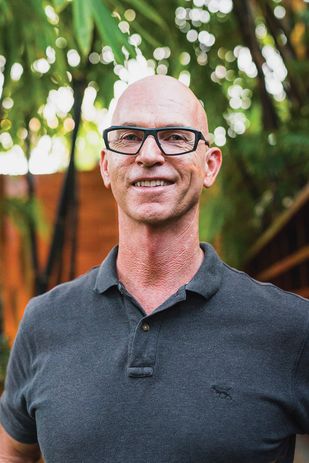

Landscape designer Steven Clegg, principal of Steven Clegg Design.

Image: courtesy Steven Clegg Design

Like any true gardener, Steven Clegg’s knowledge and love of plants is deeply rooted in the soils and landscapes of his childhood. He recalls with fondness tinkering in his grandmother’s garden in the countryside of south-east Queensland as a young boy, digging around the flowers and fruits, the roses and hydrangeas, and purchasing seedlings wrapped in damp newspaper. A vegetable patch was par for the course for him as a teenager, and at home he took over the family garden and became an industrious potter of plants, seeking his goods at far-flung nurseries and garden shows.

“You can’t be a landscape designer unless you get your hands dirty,” he says, as he is about to celebrate the twenty-sixth anniversary of his successful design practice. He has had a predilection for “old-fashioned plants” since the days of his grandmother’s garden, and there are regular escapades to nurseries that stock “old-fashioned gems” rather than fashion-driven stock.

After studying horticulture, Clegg supervised a large production nursery before spending a decade in retail. His own business, Gardenesque, became a darling of the Brisbane design set, providing a cornucopia of furnishings, sculptures and pot plants in deliciously styled outdoor settings. “The shop developed a lovely client base,” says Clegg, “and from there I decided to concentrate on residential design rather than retail.”

Commercial work has never appealed, lacking the intense personal interaction he values so much with clients and the direct contact with architects and architecture. “I love working with architects from early on in a project,” he says. “The earlier a client brings you in the better it is. The buildings and the garden are evolving things – nothing is ever static with a garden.”

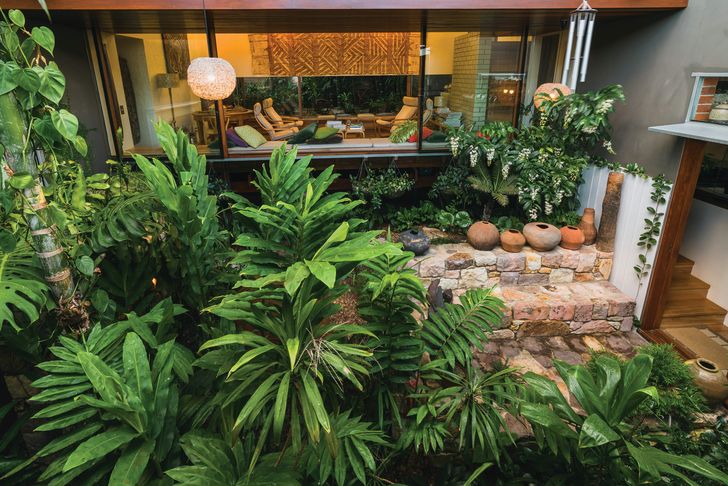

A thickly vegetated interior courtyard featuring rainforest creepers, hanging baskets and pineapples forms the central focus of Z House.

Image: Colin Hockey

Clegg collaborated closely with both architect and client in Donovan Hill’s Z House in riverside Teneriffe. Timothy Hill, director of Donovan Hill at the time, shared his vision of a house lost in and engulfed by verdant foliage. The idea merged well with Clegg’s philosophy of creating gardens that “feel as if they were always there,” and the exterior form now disintegrates beneath native wisteria, orange trumpet vines and thunbergia. The front entry tracks under a thatch of wildly crisscrossing Timor black bamboo.

“Timothy wanted to emulate the large hoop and kauri pines that stand sentinel on hills around Brisbane’s older suburbs.” Thus a tall kauri pine ( Agathis australis ) announces the presence of the building on the street corner, an appropriate rival to the tall roof frame of the entry. An interior courtyard is the home’s soul-enriching hero piece, in which lipstick plants burst from hanging baskets and a quirky pineapple or two protrude from a riot of rainforest creepers. Light is reflected and bounced around the space through carefully placed clerestories and tiled walls. Above, a roof garden is an ever-changing landscape of sculpted cairns.

Native shrubs, grasses and sculptural forms coalesce in the richly textured rear garden at Bligh Graham Architects’ Chelmer House.

Image: Colin Hockey

“We love revisiting our work and watching things grow and change,” says Clegg. Many clients enjoy the process of maintenance and further discussion and design modifications. “Not everything always works – a garden is unpredictable and we love to be able to change things as needed.”

In Chelmer House, a historic Queenslander has a beautifully modulated extension at the rear that meets the garden and brings it inside. Bligh Graham Architects has provided peel-away apertures and low-level decks at the site’s perimeter. While the front garden is a formal arrangement of box hedges, flowering shrubs and aged camphor laurels, the client requested much less predictability in the rear garden, which spills directly from the new, open spaces. Here a mix of native shrubs, grasses and spiky old favourites expresses Clegg’s delight in and understanding of textures. Tussock-like mounds of zoysia mix with clumps of walking iris and lomandra, punctuated by an unruly bottlebrush and a swathe of mother-in-law’s tongues.

A winding staircase of concrete slabs meanders up through a garden forest to Studio for Indigo Jungle.

Image: Scott Burrows

Aperture House similarly boasts a prim historic frontispiece that explodes into vaulting light wells and indoor/outdoor spaces beyond. Jayson and Melissa Blight (of Blight Rayner and Twofold Studio respectively) designed their own home with much attention to the gardens and materials of the local neighbourhood. With ledges and plinths already shaped from historic bricks in the garden, Clegg went about “blurring the boundaries” of the perimeter and reinforcing the rambling nature of a garden that would have once existed there. “We enjoyed pulling out the lovely colours of the bricks in the foliage, and rethinking plants like crucifix orchids and crepe myrtles.” The eye is immediately drawn to the garden from within, an inviting destination that continues the broadening horizon from a compressed entry to a generous expanse of sky.

Collaborating with architect Donovan Hill, Clegg engulfed the spaces of Z House in lush foliage, creating a garden with an immediate sense of establishment.

Image: Colin Hockey

Considering the exterior view from within is a starting point for most of Clegg’s work. Increasingly, small lots require deft borrowings of landscapes and carefully composed vistas from interiors. Studio for Indigo Jungle sits in a surprisingly suburban context, given that it appears to be surrounded by dense rainforest. The vista from the main house to the neighbouring studio (designed by Marc and Co for interior stylist Indigo Jungle) is alluring. A winding garden staircase of long concrete slabs meanders through the forest towards the giant A-frame aperture, only partly revealing it at any one point. Concrete pipes are used as oversized planters along the way and the palm forest is densely underplanted so that the white studio is striking within an essay of green-on-green.

A winding staircase of concrete slabs meanders up through a garden forest to Studio for Indigo Jungle.

Image: Colin Hockey

Creating a meandering entry path where none existed before was a ploy in the garden of Little Cove House in Noosa by Teeland Architects. A giant paperbark, a winding path underneath and a seat for resting and discarding shoes mitigated the severity of a flat front yard with a front door directly exposed to the street. The bromeliads that populate the space beneath the paperbark evoke the gardens of the local streetscapes that were first established in the 1960s. “The bromeliads truly come to life when the paperbark starts shedding,” says Clegg. “The dappled colours are so vibrant.” A central courtyard within the house is sprinkled with large rusting spun steel balls filled with orchids.

While Clegg is looking forward to expanding the design team and collaborating more with architects in the future, the journey to revive and celebrate old-fashioned plants continues. “There are so many proven tough plants that the industry has forgotten,” he says, listing, among others, the enduring qualities of walking iris ( Neomarcia ) and the groundcover Peperomia. His grandmother would be proud.

Source

Practice

Published online: 13 Sep 2018

Words:

Margie Fraser

Images:

Colin Hockey,

Scott Burrows

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2018