Emily Wong: Mazarine, your project brings together themes of climate change, marginalization of different communities, ecology, activism and also death, to present a proposal for Hart Island. How did this project begin?

Jialin (Mazarine) Wu: I love to read and often write notes in my notebook. One of my notes said, “What if all building and garden materials were degradable, and would disappear with time? What would change in this ever-changing landscape and how would it inform our attitudes towards nature and artificial landscapes?” That was the starting point of the project. The concept of [exploring the idea of] “vanishing” was so strong at this first stage and then [in the next stage of research] we started looking at what social problems exist and I found my interest was actually in social justice and memorial landscapes and connecting this will all the recent news, for example, Black Lives Matter and some of the COVID-19 events happening in mainland China.

I found that I really cared about social injustice, [the plight of] marginalized groups and power dynamics. During my site investigations, I found a piece of land that was so interesting and contained all the topics that I’m interested in. I took that place [Hart Island] as an opportunity to try to implant my idea of “vanishing” into that landscape, and [in the end] it developed into a project more [encompassing] than I had ever imagined.

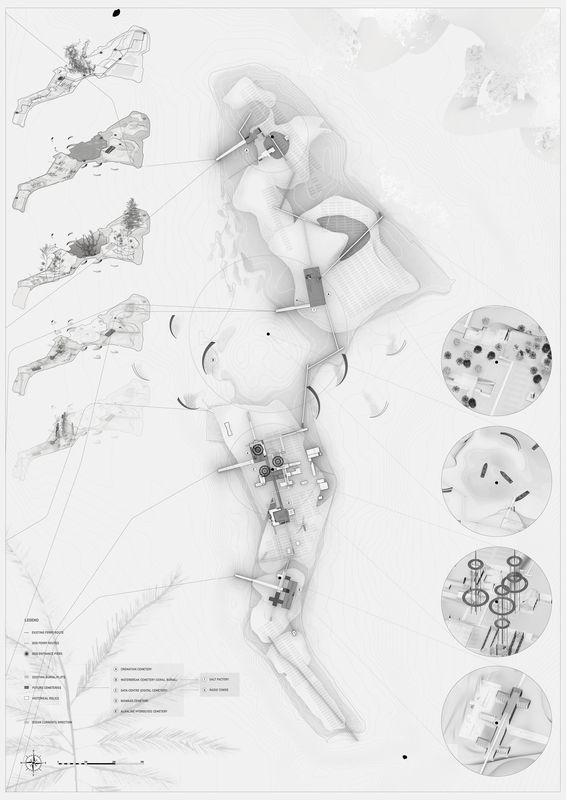

A hybrid memorial system on Hart Island.

Image: Jialin Wu

EW: I’m interested in your concept of vanishing. In your work, you talk about vanishing in a particular way, as a kind of transformation of matter into other kinds of energy. Could you explain more?

JMW: I explored this idea with help from Heike, because at first I had only thought about vanishing as, [for instance], letting land sink into the sea because we cannot control climate change. Why are our attitudes towards climate change so about being in combat with nature, rather than cooperating with nature? That was the starting point: I was thinking about the disappearance of land, sinking into the sea.

After that we did a lot of abstract concept testing and Heike [prompted] me to think about how materials might be transformed in chemical reactions such as burning. Then I tried to combine all this abstract testing into a linear storyline for exploring, what does vanishing mean? Vanishing [for me] became not only about disappearance, but about activating the unseen part of our environmental systems.

EW: In the introduction to your project, you quote Foucault who stated that “Knowledge is not for knowing: knowledge is for cutting.” What does this mean for you?

JMW: I think it’s about understanding knowledge as a kind of process, not as an end of our exploration. Vanishing Landscape is about thinking about landscape as a process, not as a steady thing that is built and then just lives there.

EW: Were there particular theories or precedents that shaped your approach?

JMW: Some of the films and TV series recommended by Heike were the most helpful. Years and Years, [a mini-series] about social change uses a time lens and makes a lot of predictions about the future based on [current] reality.

Also Christopher Nolan’s Inception and Villeneuve’s Dune. Both taught me about how to arrange timing from a director’s perspective. One of my key theoretical frameworks was derived from Nolan’s arrangement of time in his film, and also by the idea of fictions about time, for example, in the film Looper by Rian Johnson. Another framework was generated by research into Super Studio’s work – I love them so much – and Rem Koolhaas’s book Delirious New York, in addition to landscape projects and art projects like Olafur Eliasson’s Ice Watch.

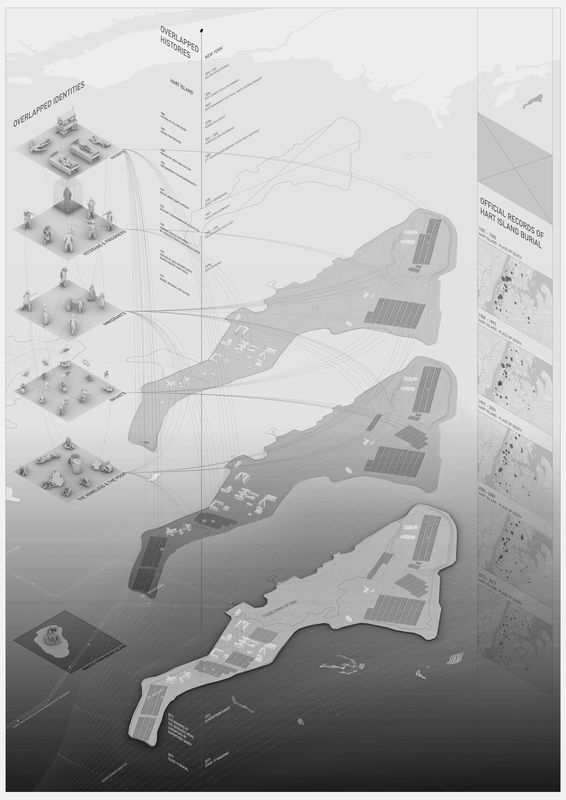

Power systems and the landscape of New York.

Image: Jialin Wu

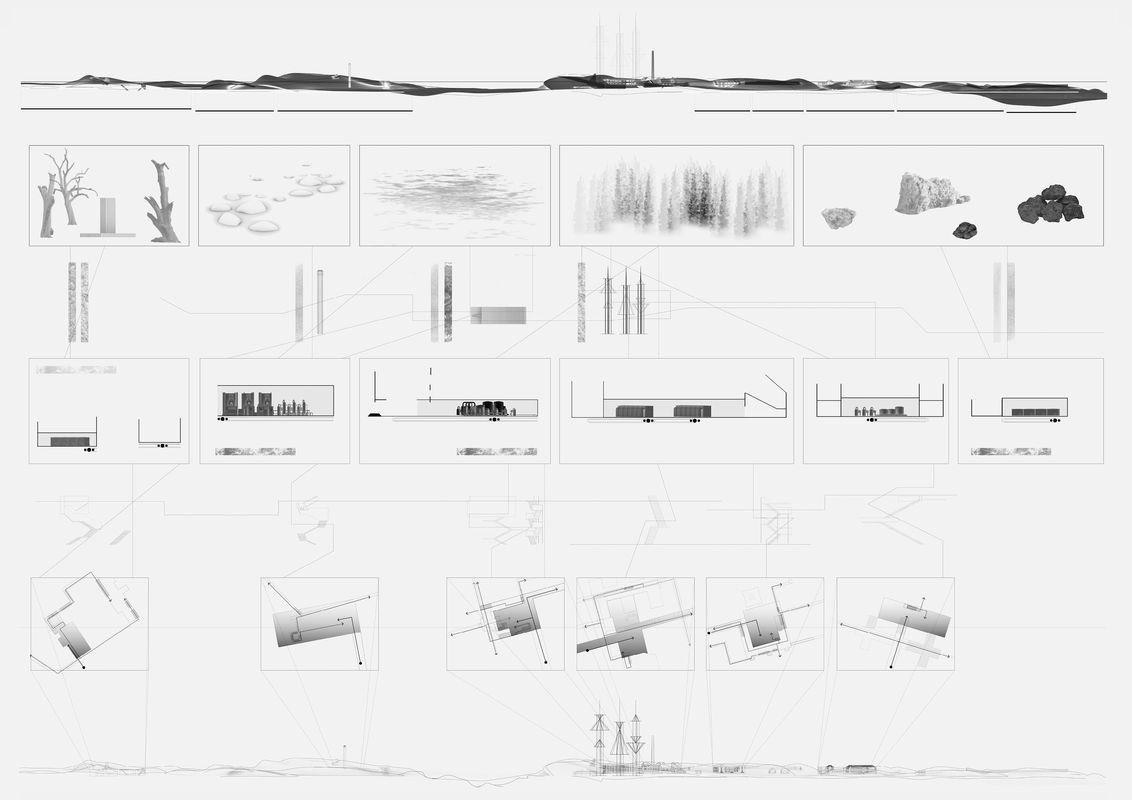

Melting and eroding.

Image: Jialin Wu

EW: Could you talk about stealth activism in relation to your project?

JMW: I think in the current situation, say you are working for a landscape architecture firm, most clients probably won’t care so much about who [their projects] are going to exclude and what the historical context of the site you are working on is. But for me, landscape architecture should be a tool to help those people who are more disadvantaged in the community in the design of public space. The different sides of the project came about because I wanted this project to be both pragmatic [in terms of actually being able to be commissioned by a client or the government], and also to care for the marginalized.

Heike Rahmann: The way we started that conversation was precisely that point of, well, you could either take a very provocative radical activism approach with the project and really shake up society and shake up viewpoints, but then how can the design be something that is relatable? How can it be something that is believable? And so from very early on, the idea of stealth activism was formed. With that, there is a level of subversion and undermining [of institutions] going on, but also an acknowledgement that you’re not shaking up everything entirely because if [opinions] on the project are too polarized then we’re not moving anywhere – there would be a loud exchange of voices, but we would not necessarily be infiltrating very deep or changing much. So that’s where it started off, with this idea of government versus activism.

Mazarine’s work uses some of the more conventional modes of how we operate today – capitalist modes, capitalist choices – but the way that she applies them in the design is about starting to slowly infiltrate and slowly achieve change in a broader sense.

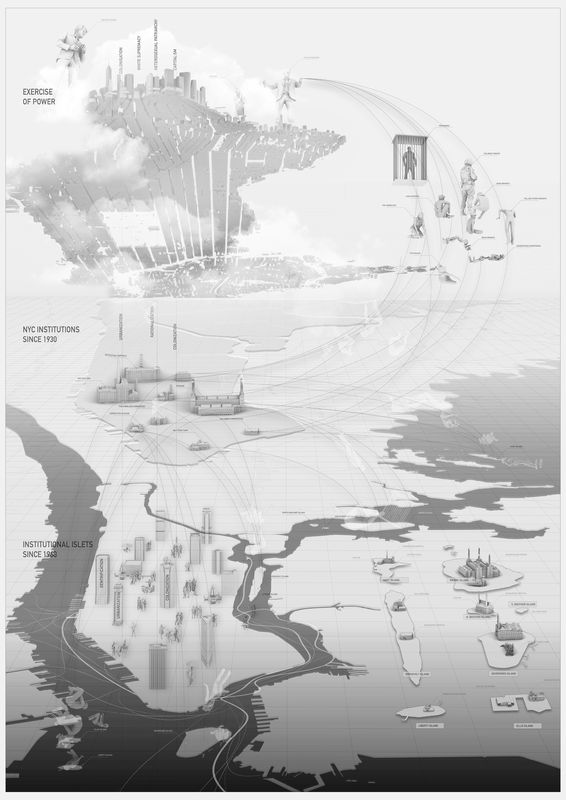

Vanishing to activation.

Image: Jialin Wu

EW: Your proposal argues that remembrance can be an active political action, not just passive recollection and can be a vehicle for collective resistance.

JMW: This approach draws on precedents about memorial landscapes, and the view that they are stable and something we should live forever. This doesn’t work – nothing is eternal and with time comes change. I think that in a real memorial landscape, the forms are not so important – we will always remember what it means for us. My approach was to deconstruct forms of remembering and try to make them finally become invisible.

For example, my [proposal to broadcast the voices of the marginalized deceased] is about remembering those people with electricity waves, with all things disappearing, vanishing, in the project’s last stage. Deconstructing the form is the only way that I can think about activating empathy for marginalized people.

I build everything up and then let it vanish [over] time. The whole process is about telling you that remembering is not about being attached to one [eternal] form. [Memories and the voices of the dead] will talk with you every time you come to a site and changes over time will help you to form a conversation between the deceased and the present or anything else in our natural environment.

HR: Mazarine’s project develops a timeline that tries to talk about these different layers of memorialization that happen – both on an individual basis, but also, as part of a collective – as something that is happening physically, but also metaphysically, that draws in the landscape as constantly changing and that allows us to continuously look for something new while also continuously remembering. That part of the project is saying that the memorialization goes beyond the individual deceased person who was marginalized in their lifetime. As the design proposes a large-scale memorial, it is a celebration of otherwise marginalized communities. So this is for both the deceased and the people remembering and wanting or needing to remember. As such it offers an individual take, while you’re also part of a larger collective.

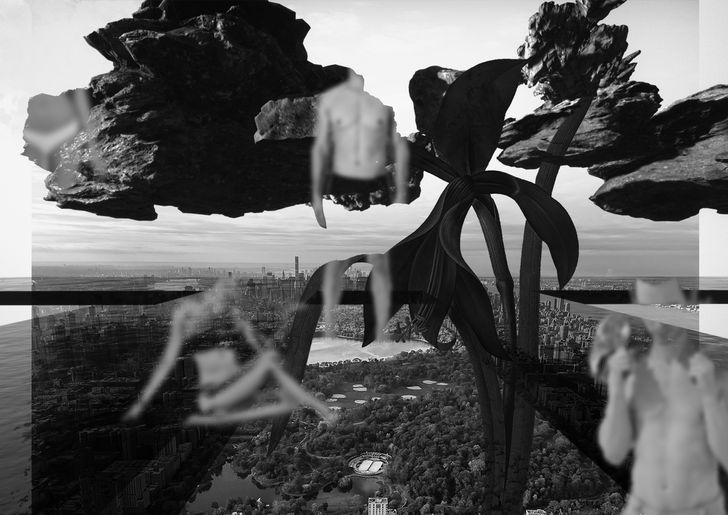

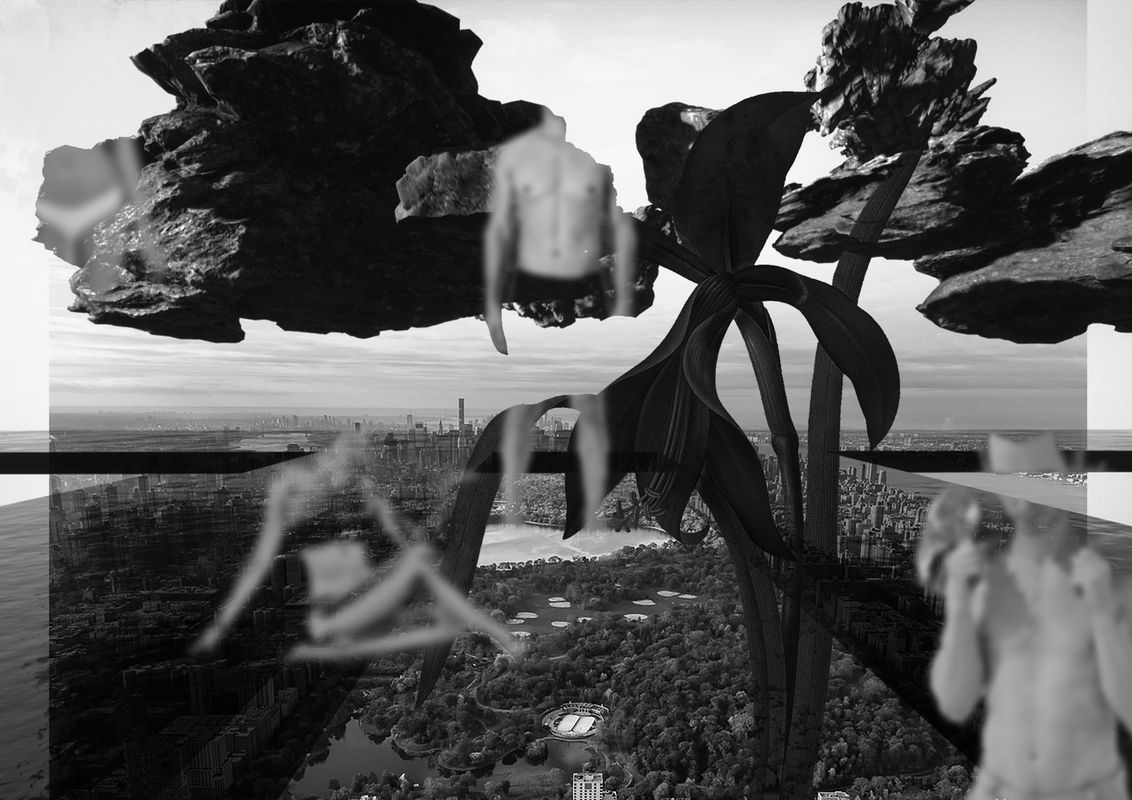

An invitation: when rocks become clouds.

Image: Jialin Wu

EW: One final question for you, Mazarine, what are you headed now? Have you graduated from your masters at RMIT?

JMW: Not yet, I’m actually on exchange, studying at the The Chinese University of Hong Kong and trying to apply some of these radical architectural ideas into urban design. I’m not entirely sure what I’m going to produce, but it’s exciting because I’ve got a starting point – a direction, but the outcome is still open. Maybe it will be a “vanishing city”? I’m also looking at materiality and the specific qualities of concrete. Vanishing Landscape explored some material thinking and I would like to learn more about building materials – bricks, concrete – and their performance. But also beyond appearance and form, what the spiritual side of these materials [might lend to] design.

EW: It sounds like there’s quite a clear link between what you’re working on now and the ideas you’ve investigated through Vanishing Landscape.

JMW: I’m not a very theoretical framework person. I don’t feel like I know much about theory – I just love to dig into design and mixing materials. In our class discussions, every time I think about philosophy in my head, it feels chaotic! But Heike always knows what I’m talking about and I really appreciate that.

HR: I think we were always working together collaboratively, trying to make sense of things.

To read Jialin (Mazarine) Wu’s project statement for Vanishing Landscape, go here.

To view all the winners of the 2021 Landscape Student Prize, go here.