If we came across a man who every day took a brick out of the walls of his house without considering that eventually the house would collapse, then we would be concerned about his mental state. Yet humans continue to consume and pollute the natural environment, upon which the long-term survival of our species depends. Such behaviour reflects the widely held attitude that nature is a free commodity – an idea that has prevailed since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and has led to the current twin global emergencies of climate change and species extinction. The consequences of this attitude are becoming clearly manifest in the acceleration of severe climate change events and the rapid global loss of biodiversity.

The extent to which biodiversity has been diminished by human activities is highlighted in The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review,1 an independent global review of how ecosystem processes are affected by economic activity. It was commissioned in 2019 by the UK government’s economic and finance ministry and supported by an advisory panel drawn from across public policy, science, economics, finance and business. The review points out that humans and the livestock that we rear for food now constitute 96 percent of the mass of all mammals on the earth. Poultry, raised primarily for human consumption, make up 70 percent of all birds currently alive.

The concept of biodiversity offsets sits within the frame of this attitude toward the human/nature relationship. Unfortunately, it is based on two flawed assumptions. First, the assumption that natural environments can be destroyed in one area, and then re-created somewhere else to match the complexity and functions of the original ecosystem, is not supported by research. The National Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration in Australia, for instance, notes: “The promise of restoration cannot be invoked as a justification for destroying or damaging existing ecosystems because functional natural ecosystems are not transportable or easily rebuilt once damaged, and the success of ecological restoration cannot be assured.”2

Second, the assumption that biodiversity values can be accurately translated into dollar values for offset credits that are bought and sold in an efficient market system is speculative at best. In a market system based on the exchange of goods and services, economists generally treat the consumption of natural environments as an externality that sits outside of, and is not accounted for in, the market system. Where an activity creates a harmful externality, such as the destruction of natural environments, a common approach taken by governments is to impose a levy, referred to as a Pigouvian tax, where the revenue from the tax is used to fund mitigation of the negative externality impact.

The Biodiversity Offsets Scheme established by the New South Wales government under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 can be seen as a form of Pigouvian tax levied on landowners to allow them to clear remnant native vegetation for development. But rather than the state government collecting the tax and directly funding mitigation actions, the scheme involves the purchase of biodiversity offset credits through a quasi-market system. Under the scheme, if a developer or landowner wishes to clear native vegetation, they can purchase offset credits from the Biodiversity Conservation Fund. The price for the offset credits is determined by the Biodiversity Offset Payment Calculator (BOPC) created by the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment.3 Payments for offset credits are made into the Biodiversity Conservation Fund and responsibility for finding a suitable offset is then transferred to the fund, and the landowner can proceed with vegetation clearing.

The fund then identifies areas of remnant vegetation to create the biodiversity offset by negotiating a Biodiversity Stewardship Agreement (BSA) between the landowner and the minister. However, the value of the BSA is not determined by the BOPC that was used to calculate the offset credit price; rather, it is negotiated between the parties. Consequently, there is not a direct link between supply and demand, which is a key component of an efficient market.

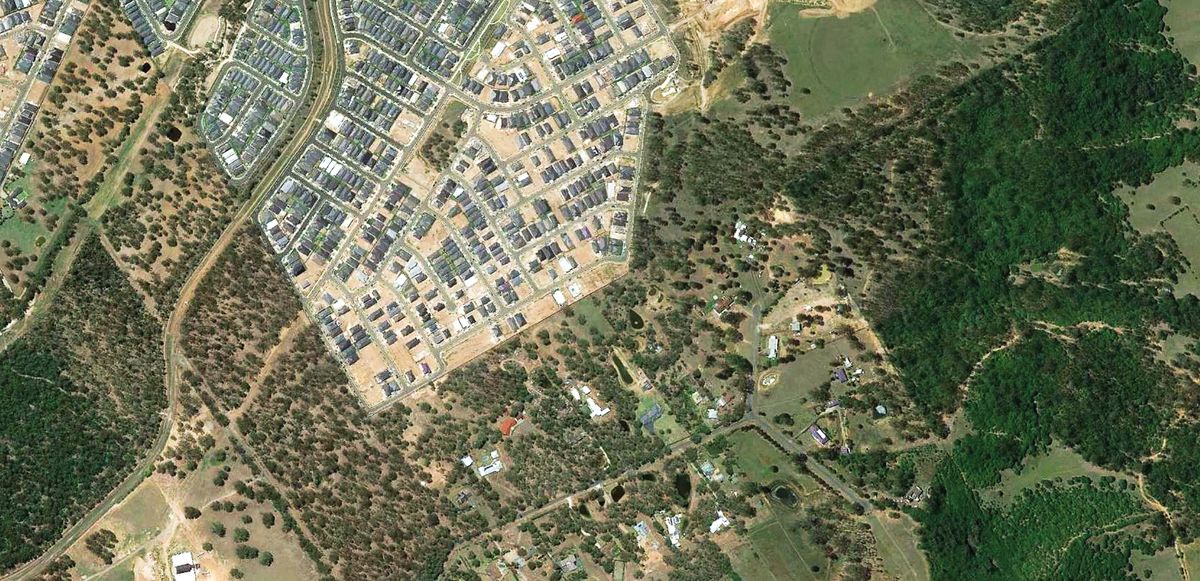

An outer suburban residential development in New South Wales on land cleared of all vegetation.

Image: Google Earth, 2021

This flaw in the scheme is demonstrated by the suspension of the BOPC since the 2020 September quarter, due to the decline in BSA activity. The price charged for the offset credits has been artificially fixed at the price applicable prior to the BOPC suspension, rather than allowing the price to increase to match supply.

Even if the area of land brought under BSA protection is comparable in hectares to the area of remnant vegetation cleared, there will still be a net loss of biodiversity. This is because the areas covered by BSAs already contain biodiversity values and, while the BSAs may result in an increase in those values over time, the amount of increase cannot match the biodiversity values of the remnant vegetation that is destroyed by clearing.

Serious concerns about the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme have prompted the establishment of a NSW government parliamentary inquiry, which is due to report to parliament by 1 March 2022. These concerns arose when a state government agency purchased biodiversity offsets from a company with links to a consulting firm that was advising the same agency on its credit obligations under the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme.4 This failure of governance raises further doubts about the effectiveness of the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme in achieving the aim of biodiversity conservation.

However, it is important to acknowledge that the economic model on which the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme is based is a set of assumptions that can be changed through discussion and agreement to better achieve the intended goals of the scheme. In her 2017 book Doughnut Economics,5 Kate Raworth argues for the need to adapt the global economic model so that we invest in all sources of wealth. These include natural, human, social, cultural and physical components of the economy, from which all values ultimately flow, even if they are not recognized in monetary terms. A rebalancing of the roles of the “market,” “state,” “commons” and “home” economies is required to achieve a sustainable provision of human needs, together with resilient natural systems. Attempting to achieve biodiversity conservation by apply a market system that treats it as a tradable commodity fails to capture the full range of biodiversity values, which cannot all be expressed in monetary terms.

The Bungarribee Estate residential area, which abuts the Cumberland Plain Woodland in south-west Sydney.

Image: Noel Corkery

There is an urgent need for a global shift in perspective away from one of consumption and pollution of natural environments, to one of responsibility for their protection and repair, and nurturing of biodiversity, so that both human society and natural systems can survive and prosper. Such a perspective would be more aligned with that of First Nations peoples in Australia, whose relationship to the world is based on human-nature connectedness. This is expressed by the saying: “Healthy Country, healthy people.”6 The Reconciliation Action Plan adopted by the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects in 2018 encourages the adoption

of a “Connection to Country” approach to landscape planning, design and management across the full range of project types and scales.

The need for this shift in perspective was recognized by the United Nations Statistical Commission through the System of Environmental Economic Accounting – Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA),7 which was adopted in March 2021 by more than 34 countries, including Australia. The SEEA EA framework provides for overarching questions to be addressed about the relationship between the economy, society, the environment and how human wellbeing and social progress are measured. The concept of biodiversity offsets in the context of urban development needs to be fundamentally rethought, beginning with the crucial question: “Can biodiversity be protected, restored and sustainably managed while still allowing for urban development?” The answer will require a major shift in the mindset of policymakers and government authorities toward biodiversity.

The Cumberland Plain Woodland in Western Sydney is an endangered ecological community threatened by land clearing for agriculture and urban sprawl.

Image: Noel Corkery

Governments must acknowledge their responsibility for the protection, repair and nurturing of biodiversity in accordance with city-wide and regional strategic plans. The extent of biodiversity values, on both public and private lands, needs to be accurately and comprehensively documented. Protection and management could then be achieved through a combination of adjustments to land-use plans to retain remaining native vegetation, conservation agreements with landowners and government acquisition of land for permanent protection of biodiversity values and ecological restoration to reconnect fragmented remnants.

Landscape architects have an important role in this process through their involvement in projects that can impact areas with significant biodiversity values. It is essential to have a sound understanding of those biodiversity values and the limitations of offset schemes. Equally important is a commitment to find opportunities to protect, restore and manage biodiversity values through good site planning and landscape design.

1. Partha Dasgupta, The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, HM Treasury, 2 February 2021, gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review (accessed 29 November 2021).

2. Standards Reference Group SERA, National Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration in Australia, 2021, Edition 2.2. Society for Ecological Restoration Australasia.

3. NSW Government, Biodiversity Offset Payment Calculator, lmbc.nsw.gov.au/offsetpaycalc (accessed 29 November 2021).

4. Lisa Cox, “‘Deeply concerning’: government consultant made millions from NSW environmental offsets,” The Guardian, 28 Apr 2021, theguardian.com/environment/2021/apr/28/deeply-concerning-government-consultant-made-millions-from-nsw-environmental-offsets (accessed 29 November 2021).

5. Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist (London: Random House Business, 2017).

6. Liz Cameron, “’Healthy Country, Healthy People’: Aboriginal Embodied Knowledge Systems in Human/Nature Interrelationships,” The International Journal of Ecopsychology, vol 1 no 1, 2020, digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/ije/vol1/iss1/3 (accessed 29 November 2021).

7. United Nations Statistical Commission, “System of Environmental-Economic Accounting – Ecosystem Accounting,” United Nations, seea.un.org/ecosystem-accounting (accessed 1 October 2021).

Source

Practice

Published online: 21 Feb 2022

Words:

Noel Corkery

Images:

Google Earth, 2021,

Noel Corkery

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2022