In early 2021, I hosted the Parlour Instagram account. I didn’t realise that it was going to be such a cathartic and formative exercise.

Instagram for me is a playful and social space to interact with friends and family. It’s a platform where I share and engage in both my passion for landscape architecture and my queer identity. This intersection often creates interesting dialogues, crossovers and learnings. As it turns out, a lot of queer people are interested in gardening and plants, and many landscape architects understand and create space for queerness. Then Parlour invited me to distil pictures into words and convert the image and captions into a written summary. As my posts are self-reflections, I feel I need to give a bit of personal background.

I started landscape architecture at RMIT University straight after completing high school in a small country town in north-west Victoria. For the first couple of years, I embraced city life and preferred to spend my time at gay bars doing queer performances, embracing my new-found community and freely expressing my identity.

After dragging myself through two years of uni, I jumped at the opportunity to study in Berlin. Surprisingly, I didn’t head straight to the city’s notorious Berghain and ditch the studies altogether. Instead, I studied gender theory and queer history at Humboldt University. I immersed myself in discourse that simultaneously dismantled the gender binary and created a world I could live in. I learned about performative intersections of identities and transformative ideas of space. I familiarised myself with theorists such as Kate Bornstein, Judith Butler and Katarina Bonnevier.

Back in Melbourne, I embarked on my Major Design Project (now Master’s thesis) entitled Queer Feminist Landscape Architecture back at RMIT. I didn’t know how, but I believed it was possible to intersect my studies in Berlin with the practice of landscape architecture.

I worked hard through design testing and worried endlessly that what I was exploring wasn’t valid. I wasn’t certain where the work was going, there was no precedent to lean on. After six months of design research, a lecturer, upon looking at my work, demanded to know what “queer” was. At the age of 22, I didn’t yet have the language to respond and I certainly didn’t want to share details of my own queer identity here, with this person. The questions felt so personal, when the work I had pinned up hadn’t been about what queer was, but had instead been about respect, equality, community, memory and understanding. One of the project’s installations, for instance, had involved hand-made flags installed onto Princes Bridge along Melbourne’s Yarra River (Birrarung). The flags had been made by a collective of queer people in a squat in Melbourne’s inner north and each bore the name of Melbourne female1 queer performers and community leaders – Sprinkle Magic, Yana Alana, Bumpy – to name a few. I had wanted to celebrate these people as role models and for their contribution to Melbourne’s queer community, and so the work was about visibility, respect, equality, community, memory and understanding, rather than about defining the boundaries of queer.

Despite my feelings of discomfort that arose from the lecturer’s comments, I was lucky to have a strong community, supportive family and allies elsewhere, and I continued with the work, which went on to receive both the Fitzgerald Frisby Landscape Architects Community Award and the Stutterheim and Anderson Landscape Architects Innovation in Landscape Architecture Spatial Design Award at RMIT in 2008.

Image: Marti Fooks

The infinite value of queerness

Integral to queerness are concepts of community, inclusion, beauty, playfulness and safety. Queerness is asking questions and challenging structures that perpetuate homophobia, transphobia, racism and sexism.

As a practitioner, I find myself working on large, complex, multi-disciplinary projects in two major Australian cities. On these projects, I actively participate in discussion around safety and inclusion. These conversations raise many questions and many challenges.

Do normative practices of managing crime reduce a sense of safety and exclude people from place? Is the way we manage the risk of crime actually reducing a sense of safety? By applying theories of crime prevention through environmental design, are we simply ticking boxes and perpetuating the structures that exclude the voices that most need to be heard? Most importantly, can we challenge the normative structures of managing and designing public places to create equitable cities?

Because currently, we are working in a context full of paradoxes – the people who are least at risk of crime in public space still feel the most unsafe, those communities that are at risk are rarely consulted or included in design and decision-making processes, and fundamental decisions about our public spaces are frequently made by those with little design knowledge or skills.

Safety and public space

According to the statistics, women (in the word’s most inclusive sense) are afraid in our cities. Unfortunately, the analysis does not reflect the actual diversity of gender in our community.

Yet the data also tell us that violence is much more likely to occur in private environments. According to the most recent data on incidents of physical assault by a male, women are most likely to be physically assaulted by a man they know (92 percent). The location of these incidents is most likely to be the home (65 percent).2

So if the majority of harm is occurring in the home, why are women less likely to use public space?

The data tell us that between 2005 and 2016, men were more likely to walk in their local area alone after dark than women (68 percent of men and 39 percent of women in both 2005 and 2016). As a result, women gain fewer health and wellbeing benefits from public space than men, missing out on after-dark public activities like taking a walk with the dog, getting some fresh air or visiting friends.

So how can landscape architects understand more of our responsibility for safety and access for women and queer people? What new processes can ensure the voices of those most at risk are heard?

Unfortunately, in current government planning and design processes, unqualified professionals often make poor recommendations and decisions that affect urban environments under the guise of safety. Inappropriately qualified people risk substituting their own biases, subconscious or otherwise, for professional rigour. I have heard such biases negatively impact design outcomes.

On one project, the lighting scheme on one side of a development was to deter occupation; on the other, lighting was to be ambient and welcoming. This difference stemmed from a security consultant’s observation during one night-time site walk that Aboriginal people “loitered” in public space.

When people of colour enjoy public space, bias leads some people to perceive these groups as “loitering.” Similarly, when groups are queer, they can be perceived as “sexualising” the public space. But when groups are white and gender-normative? That’s “site activation.”

Image: Marti Fooks

The challenges of CPTED

The most prevalent framework for understanding safety and public space is Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED). It takes five days to become a CPTED practitioner, and the course is run by the New South Wales Police Force.

Following the training, professional security engineers, planning, lighting design, architects, police and community members become CPTED auditors who are capable of preparing design review and risk assessments.

CPTED principles and practices shape the design of our public spaces in many ways, yet their origins are in control and incarceration. The first generation of principles derived in the 1970s were designed to control inmates. They were not intended to make people feel or be safer.

CPTED theories have evolved over the years. However, they still go directly against my expertise as an urban designer and landscape architect.

Challenges include:

- The historic background of CPTED design principles is to control people, not to make them feel or be safer.

- The voices of people from diverse backgrounds, culture and identity are underrepresented in the process.

- Physical outcomes ignore social, environmental, economic and cultural factors of site.

- Acts of crime are determined by the State and may not be consistent with community ideals.

- CPTED places a focus on persecuting the offender after the crime/harm has occurred.

- Physical modifications are often delivered by representatives who may not be suitably trained.

- Insufficient attention is paid to research evidence about the effectiveness of certain techniques, and strategies are not sufficiently evaluated.

Can this problematic structure be rewritten, or should we start again at square one?

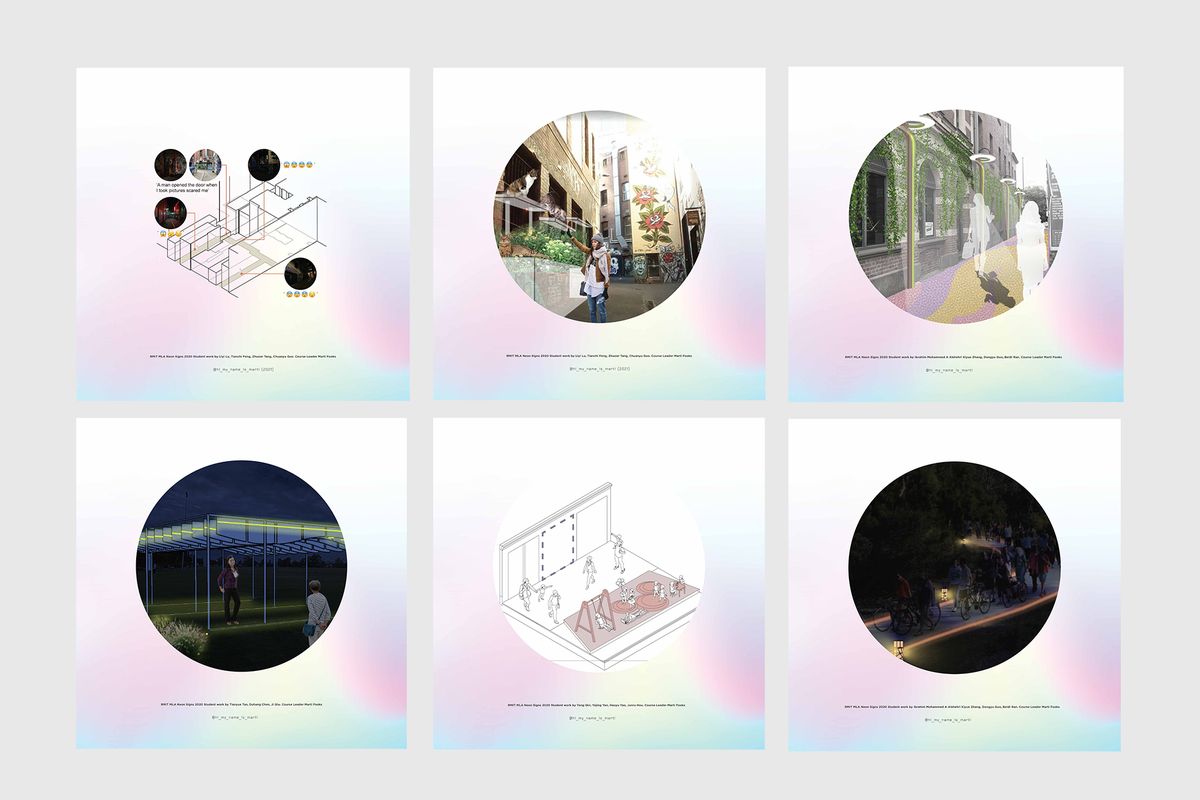

Image: Marti Fooks

Where to from here?

Design alone won’t make our cities safer, but designers must play a key role.

As landscape architects, we design and plan public spaces, but the problems facing women and queer communities are not exclusively in the public realm.

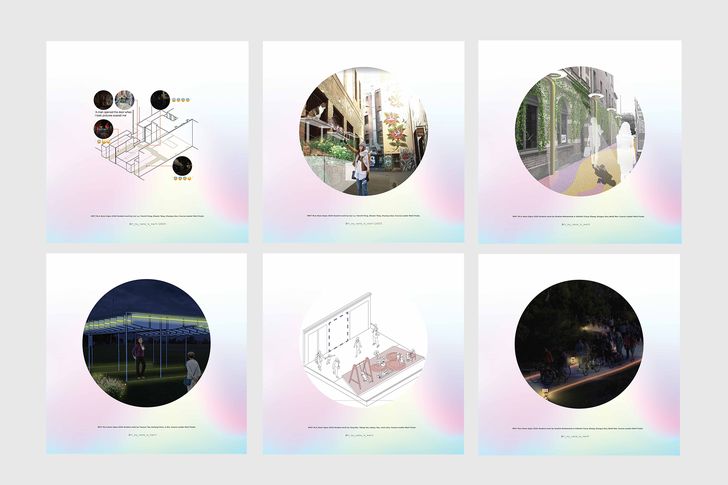

I don’t know exactly what comes after Safer by Design or CPTED, but we do need new ideas. As part of the effort to find them, I lead a research seminar at RMIT University titled “Neon Signs, New Ideas for Safer Cities” in the Master of Landscape Architecture course.

The seminar aims to explore how landscape architecture and designers can rethink the design principles and risk assessments to respond to contemporary pressures on our urban places while putting the safety of women, LGBTIQ+ people, and people of colour (some of the groups most at risk in our public spaces) at the forefront.

I also believe we need new tools. Designers need new processes that embed the people who are most at risk within the design process. While we are working on new process, we also need to stop seeing safer design as a tick-box exercise.

I don’t care how many pathways there are in and out of your development: if you don’t truly care about creating safe cities and have this commitment embedded in your process, then you are safe-washing.

So this is a call-out, to call it out.

If you hear unfounded assumptions creeping through in project processes, say something. Demand that the project invests in a proper process.

If you want to make a place safe, ask who it is safe for – and safe from.

This article was originally published by Parlour.

1. “Female” is meant here in the word’s most inclusive sense

2. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Personal Safety. Australia, 2016, abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/personal-safety-australia/latest-release (accessed 5 October 2021)