The massive investment made to host Olympic Games is usually rationalized by the global exposure that the event brings and the facilities it generates. Since the earliest conversations in Brisbane, the focus has been on the opportunity for positive urban transformation of the kind achieved by significant, but well-targeted, investment. Proponents cite precedents such as Barcelona, Sydney, Vancouver and London, where bold, visionary Olympic investment drove urban renewal and became a catalyst for broader urban change. What did these cities do differently to the many former Olympic hosts where no such legacy resulted? They concentrated investment not only in the individual facilities necessary for the event; instead, whole precincts and even territories were recast, in physical form and, just as importantly, in the collective imagination of their communities. For these cities, the “lasting legacy” was hundreds and even thousands of hectares of dysfunctional urban wasteland remade into healthy, functioning places where urban dwellers could proudly live, work and even love.

Similar transformations resulted, on a smaller scale, when Brisbane hosted the Commonwealth Games in 1982 and World Expo 88 in 1988. These events are credited with elevating the city’s image from country town to internationally connected, urbane and energetic city of unique subtropical character. Expo 88 yielded South Bank, a 42-hectare subtropical haven created from post-industrial land that took the central business district across the river into new territory. The region’s first contemporary mixed-use urban precinct, South Bank became the model for multiple urban transformations across the state. The 2018 Commonwealth Games on the Gold Coast delivered a new knowledge precinct and village focused around the Griffith University Gold Coast campus and the Gold Coast University Hospital. This precinct is a terminus for the initial stage of a city-wide light rail that is transforming public transport in this sprawling conurbation.

Lasting legacies require transformation not only of the form and operation of urban places, but of urban thinking by their communities and the urban professionals who serve those communities over ensuing generations. When each project contributes to a better understanding of urban quality, improvements are achieved across the system.In Barcelona, Sydney and London, the entire city has benefitted post-Olympics from revitalized urban precincts as well as from a shared sense of urban potential and a generation of urban professionals working in new ways to deliver what their cities need over subsequent decades. Not only have urban renewal practices improved in these cities, but delivery mechanisms such as open design competitions and design review have been normalized. Communities and their places have been enlivened in the process.

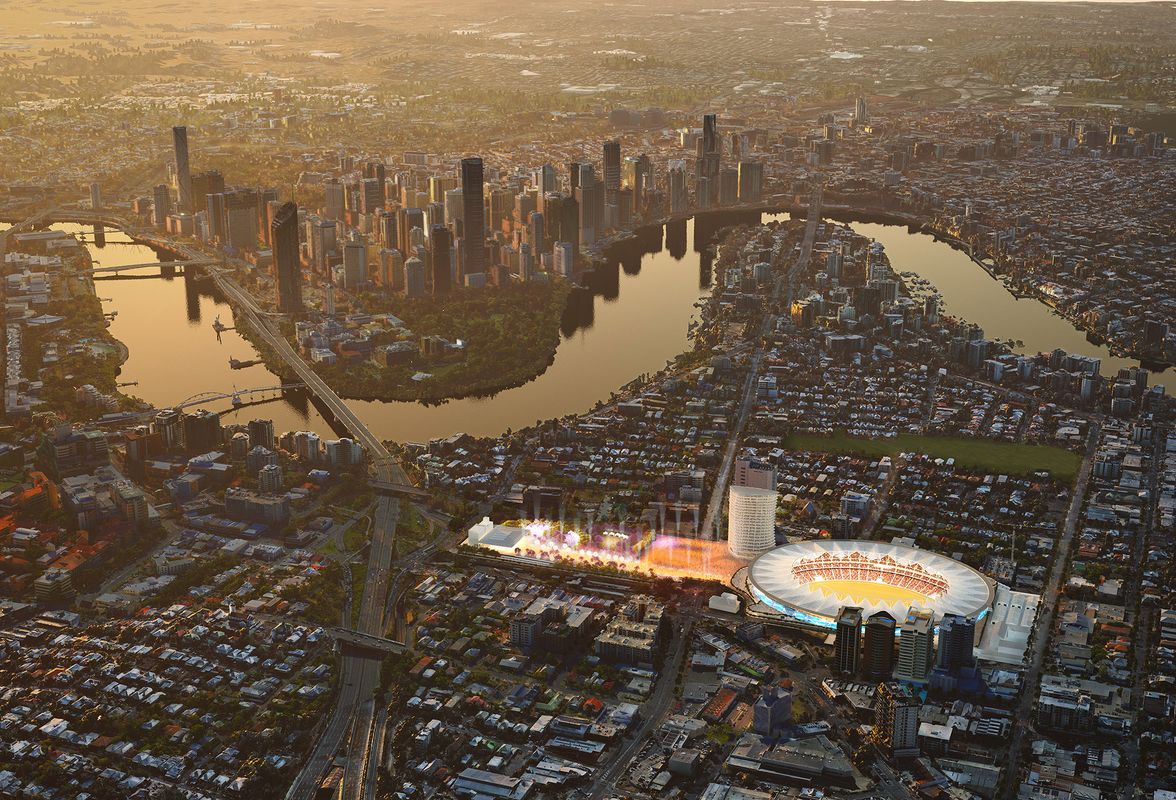

Concept plans for Brisbane Live.

Image: Archipelago, Woods Bagot and Populous

Where lasting legacies have been achieved, urbanists and designers with skill, vision and imagination have been commissioned early in the Olympics preparation process to explore and demonstrate new ways in which the city might work. They have been willing to articulate the case for change at an urban scale, rather than focusing on single facilities. Their proposals have been tested and debated in the public domain. In turn, leaders, bureaucrats and urban managers have been willing to engage with these specialists – often publicly – in important but inevitably challenging conversations about what form the future city should take, how each project might or might not promote that form, and why business-as-usual delivery processes may not deliver what is actually needed. Independent development authorities with the capacity to cut across entrenched patterns of planning, design, discourse and delivery were vital to manage this complex process.

Urban professionals of all persuasions – urban designers, planners, architects, landscape architects, engineers and construction specialists – were essential to success in these cities, skilling up and performing in the hothouse atmosphere engendered by projects delivered in the public eye and for an international audience. The result was an expanded cohort of urban specialists capable of delivering new forms of urbanity, in new ways, wherever transformation is needed.

In Brisbane today, a nascent sense of shared aspiration is apparent. To date, the emphasis has been on investing in facilities that already exist to make them more accessible to their immediate precincts (through pedestrian mobility/walkability) and to the region as a whole (via high-speed rail and light rail). Implicit in this is the recognition that while Queensland can provide individual facilities and locales of value, it struggles to create well-connected, accessible precincts that successfully combine multiple activities and multiple mobilities. Major facilities such as the Brisbane Cricket Ground (Gabba), Suncorp Stadium, Victoria Park/Barrambin and Raymond Park – all of which will be important venues in 2032 – remain uncomfortable for pedestrians to access, despite being so near to the CBD and South Bank. The urban challenge for South East Queensland now is to go beyond a “city of bits” to manifest livable subtropical urbanity, integrated from the pedestrian to the regional scale and memorable for its journeys. Former Olympic cities demonstrate that to achieve change at this scale, not only do new forms of urbanity need to be imagined from the start, but new ways of working are necessary to bring them into being. It is this expanded capacity to deliver, by urban professionals and authorities, that enables the creation of great new places, and in turn fosters a new and shared sense of urban appreciation.

Right now, urban professionals in Queensland are asking whether lasting legacies for their region are being conceptualized, debated, budgeted and initiated. Will there be an independent authority with the charter, capacity and commitment to deliver them? Will the Brisbane Olympics not only generate new facilities but enrich and strengthen urban communities, professionals and instrumentalities? New ways of making and doing take time to be tested and made workable; nine years is short for a venture of this scale.

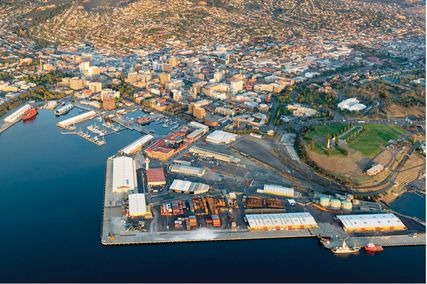

At the time of writing, an organizing committee has been established that is responsible for the event overlay, temporary infrastructure and community engagement. A consultancy is underway to advise government on what a lasting legacy might mean. A delivery authority is yet to be announced. Projects that have been mooted include an athletes’ village at Northshore and a wholesale redevelopment of the Brisbane Cricket Ground (the Gabba) as the main Olympic stadium. In both cases, professionals and the local media have expressed significant concerns. Northshore is isolated from transport routes, services and employment, while the complex and constrained Gabba site would be costly and challenging to redevelop. Such proposals are not building confidence that investment will target the legacies warranted by the region. As proud Olympic hosts, Brisbanites expect our city to be improved – quite tangibly – by legacies that really do last. We look forward to being convinced as to how.

– Catherin Bull is emeritus professor of landscape architecture at the University of Melbourne and an adjunct professor at QUT. She has served as a member of design panels in South Australia, Canberra, Brisbane and Sydney, and was involved in the Sydney 2000 Olympics for 15 years, pre- and post-event.