Australia’s biggest cities steal the show. Recognizable projects in the capitals and from the awards grace many a design practice’s boardroom. But what about the regions and our so-called “second-tier” cities – places like Newcastle, Wollongong, Geelong, Bendigo and Ballarat, Mandurah, the Gold Coast, Cairns and Toowoomba?1 These areas are growing rapidly, but is the built environment and landscape architecture keeping up? And beyond the designer-ly gaze and institutions of our capitals, what kind of contributions are being made to make a difference and help define the identities of these cities?

Australian cities are a puzzle – and the more challenging a puzzle, the more satisfying the end result. But in cities, the pieces are rarely all in focus: edges may be worn, pieces missing and thus the city remains incomplete, a project seemingly without an end. In fact, every day the city is made anew, either by design or inertia, through minor iterative adjustments that earn, by turn, the relative affection or scorn of its citizens. This is perhaps most true for our smaller cities.

As COVID showed, people are increasingly populating the regions. For instance, Geelong projects a 40.12 percent growth in population between 2023 and 2041, and Wollongong predicts a 26.04 percent growth between 2021 and 2041.2 This growth is underscored, it would appear, by millennial families looking for affordability and work/life balance. Interestingly, our regions host sizeable numbers of design professionals. AILA CEO Ben Stockwin notes that around 18 percent of AILA members are located in rural/regional areas – and, incidentally, 22 percent of our members work in local or state public practice.

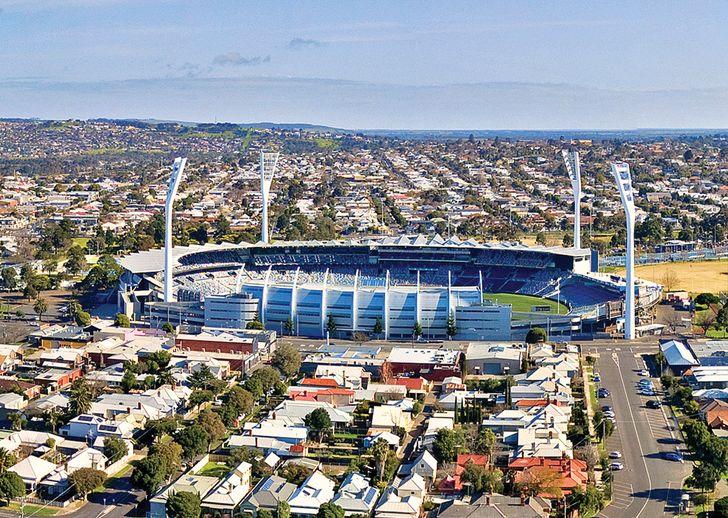

Kardinia Park Stadium in Geelong.

Image: Bob T, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Parachuting funds and design talent

With significant (and growing) populations and resources, the scale and immediacy of our smaller cities means that the workings of the levels of government and project outcomes are more immediate and obvious. Projects in smaller population centres are, arguably, more transparent and prone to greater public scrutiny. They are sometimes viewed with a sense of conservatism, and even a certain parochialism, by the built environment professionals who are often parachuted in to work on the most significant and well-funded projects (and who then promptly depart). Funds in these regions are often limited and while locally based staff may deliver a wide variety of services to the public, the fingerprints of built environment practitioners seem generally more scarce.

An example of a big project is the redevelopment of GMHBA Stadium at Geelong’s Kardinia Park, which is operated by Kardinia Park Stadium Trust for the state of Victoria. The Victorian government’s support of $142 millionfor the five-stage renovation will enable at least eleven AFL home games, as well as intermittent cricket matches.3, 4 While Australia undoubtedly hosts a widespread sporting culture that supports this type of high-level investment (a new AFL team and stadia are currently in the wings for Tasmania), these dollars could be used to support a wider variety of sports for all genders, ages and abilities, with widespread impact. These could include, for instance, all codes of football, outdoor gymnastics, track and field, swimming and basketball.

Where recreation segues into transport and urban planning, could we instead justify $142 million to fund separated cycleways or the refurbishment of “rails to trails” projects for cycling recreation? Or undertake game-changing tree-planting to combat the urban heat island effect? Or invest in public transport and the arts (as Geelong has not quite equally done recently)?5 In contrast to the big project, this type of design work – arguably the bulk of built environment design work – is so small as to be almost invisible; it mostly goes unnoticed and unremarked upon, yet has greater impact on the quality of day-to-day living and in the promotion of healthy lifestyles and climate-change-ready cities than many more “spectacular” projects.

Ad-hoc streetscape details have been installed by local residents in Surrey Hills, New South Wales.

Image: Cole Hendrigan

Wollongong City Council Design and Technical Services designed this raised pedestrian crossing in Helensburgh, New South Wales.

Image: Cole Hendrigan

“Der liebe Gott steckt im Detail”

Often attributed to minimalist German architect Mies van der Rohe (who probably co-opted it from the German proverb: Der liebe Gott steckt im detail), the phrase “God is in the detail” takes on a new meaning in the context of the puzzle of the city.

Consider footpaths. In many cases, a footpath with trees on the verge is a small – and quite possibly the only – public space that most of us in Australian cities use every day. When not done well, these may be uncomfortable to walk, ride, roll in a wheelchair or push a pram upon – and we will only do so because we must. When built, even to a modest standard, the humble footpath corridor can become a place to see friends and neighbours, to greet others using it, to appreciate the spotted shade of the trees, to listen to the warble of birds, to notice the small graces of gardeners, or to remark on the music coming from nearby homes. When designed well, these spaces are wide enough to feel unconstrained, set off from car traffic by a sufficient buffer. They can be destinations worth walking to, with shade, seats, kerb ramps and clear street signs that let you know the street was designed with the non-motorized user in mind. This is a small and incontrovertibly good thing, yet it is often overlooked in the annual budgets of small and large cities.

Consider also kerbs. Kerb ramps are mostly ubiquitous – and unnoticed, except where they don’t exist. These are the small renovations that open the world to parents with prams and all who are mobility-restricted (wheeled or not). Here, even subtle changes in the slope of a ramp or the lip of a gutter can make a significant difference to users’ experience of and access to the city. The design of details such as footpaths and kerbs changes the “shape” of the usable area of a city, expanding or constricting it for anyone with limited mobility.6

Improvements to the landscape of Porepunka, Victoria by MDG Landscape Architects enhance the town’s unique characteristics. The project forms part of Alpine Shire’s Better Places initiative.

Image: Cole Hendrigan

Finishing the puzzle

The city puzzle’s image and meaning changes for each person: daily, yearly and over decades. The small pieces of concrete, asphalt, flowers and insects, as well as the urban imagination, are always in flux, making designing for a stated condition or public expectation a challenging ambition. Lefebvre’s Right to the City implies that all citizens have the right to participate in the decision-making processes that shape their city’s development, and that cities should be designed and governed in a way that promotes social justice, democracy and equality.7 So, in considering the small, and our smaller cities, how might we reconcile the local, collaborative, modestly funded and iterative with the big, well-funded ideas parachuted in from larger centres and paid for remotely? Those that seemingly aspire to upgrade, to sophisticate and sometimes even sidestep the local decision-making and design processes of the regions?

In essence, what does the future hold for our regional cities? Is the import of big money and big ideas the only way forward, or will our regions and smaller cities and towns clarify their own identities by a design approach that emphasizes the quality of everyday living over grand, but less common, spectacles – matched by critical reappraisal of large funding streams to also deliver projects at the small scale?

After all, it is the multitude of small details, carefully curated, that give feeling to a city.8 Cumulatively, they create as much, if not a greater, sense of place and daily love for a city or town than a single large stadium – and often at a far smaller cost. If our second-tier cities are to thrive, to seize unique opportunities and to establish themselves as independent centres of attraction, then landscape architects are especially well positioned to help complete the puzzle by providing a unified image of the city that enables opportunities to be understood and responded to with a clear vision.9

1. Committee for Geelong, “Australia’s Gateway Cities: Gateways to Growth,” 2019, committeeforgeelong.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Australias-Gateway-Cities-Report-and-Appendices.pdf.

2. See population summaries by .id community at forecast.id.com.au/wollongong/population-summary and forecast.id.com.au/geelong/population-summary.

3. Kardinia Park Stadium Trust, “Kardinia Park Stage 5 Redevelopment,” kardiniapark.vic.gov.au/stage-5 (accessed 2 June 2023).

4. Football’s 33 hours of public use (11 three-hour games) cost $4 million/year/hour (of 8,760 hours/year). This cost only covers the fifth stage of development and does not include cleaning, maintenance or staffing.

5. “Curtain lifted on ARM’s Geelong Arts Centre design,” ArchitectureAU, 29 November 2021, architectureau.com/articles/arm-geelong-arts-centre.

6. Yi-Fu Tuan, “Place: An experiential perspective,” The Geographical Review, vol. 65, no. 2, April 1975, 151–165.

7. Henri Lefebvre, Le Droit à la Ville (Paris: Économica Anthropos, 1968).

8. J. I. Nassauer, “Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames,” Landscape, 1995, vol. 14, iss. 2, 161.

9. Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Boston: MIT Press, 1964).

Source

Practice

Published online: 19 Nov 2023

Words:

Simon Kilbane,

Cole Hendrigan

Images:

Bob T, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.,

Cole Hendrigan

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, November 2023