The signs of a crisis abound. Underwritten by global human population growth and our appetite for land and resources, potentially cataclysmic climate changes are combining to create a human-induced sixth mass extinction1 for global biodiversity, with as many as one million species now threatened with extinction.2

Creating protected areas has been recognized as a key strategy for addressing species decline. These areas offer “land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal or other effective means”3 and form the backbone of most countries’ conservation systems.4 Protected areas have steadily grown in both number and acreage since their inception.5, 6 Globally, these cover approximately 16 percent of the earth’s terrestrial surface;7 in Australia, 13,389 recognized protected areas cover 151,881,469 hectares – almost 20 percent of the continent, as of 2018.8

In late 2022, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Target Three (also called “30×30”)9 posited an urgent response to a global challenge. Ratified by more than 100 countries, including Australia, (as at 24 February 2023), the target marks each signatory’s commitment to the dedication of 30 percent of its territory to protected areas by 2030. Achieving this target on a planetary scale, however, is a tremendous task.

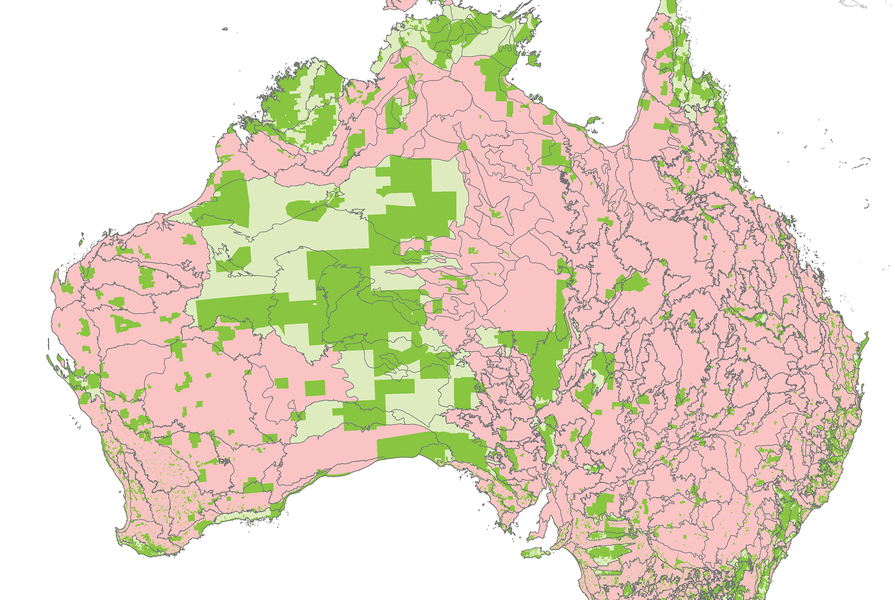

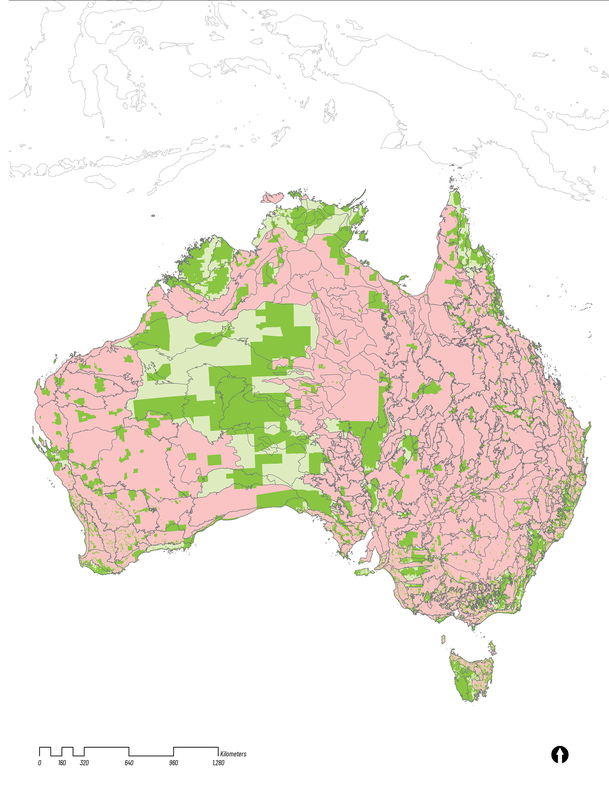

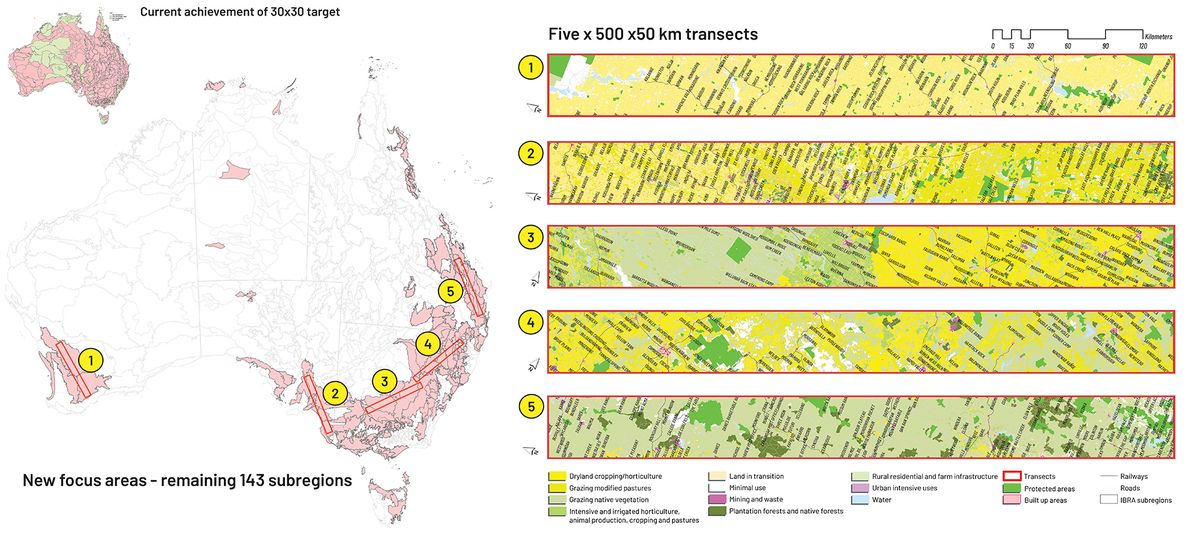

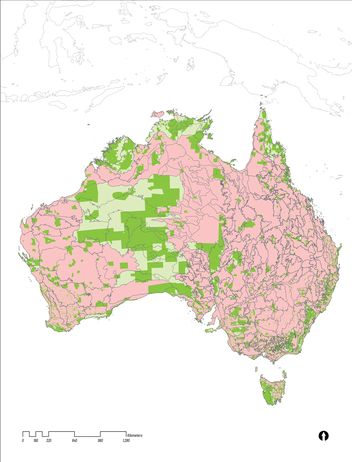

Even the national scale is daunting. Australia – with a current shortfall of about 10 percent – is still a long way from protecting 30 percent of land in total; we also have not ensured representative protection across the country to best safeguard all species, not a few. This distribution is where we really come unstuck. The Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA), which underpins the national reserve system’s 90 distinct bioregions and 421 subregions, illustrates that our existing protection is very unevenly distributed.

The most-represented protected ecoregions (and, of specific interest to this research, their subregions) exist across remote areas in central and northern Australia, where protected areas are large and far from major urban centres. Conversely, many regions (particularly those defined by intensive agricultural and urban land uses) are poorly protected, a fact made visible on the map by a matrix of small green fragments. This means that Australia does not currently meet the proposed 30×30 protection area target in 61 of its 90 IBRA bioregions and 325 of its 421 IBRA subregions; furthermore, Australia’s protected area network is highly discontinuous. This falls short of ecological best practice, which tells us that these areas should be connected. Pungetti and Jongman suggest that “if we are to retain all biotic elements in landscapes and preserve ecological functions, we need to preserve the ecological connectivity of those landscapes.”10

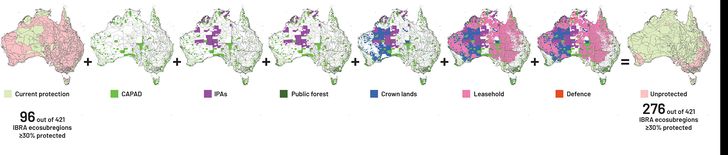

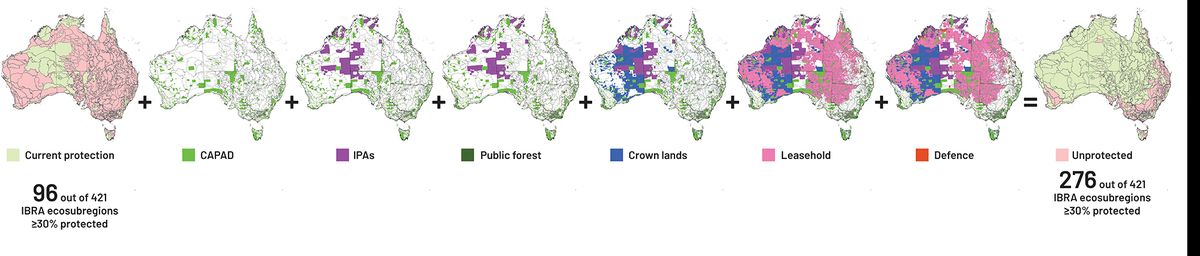

To reach the 30×30 target, the Australian government might soon consider a range of lands ripe for designation. These lowest-hanging fruit can be revealed through an examination of land tenure and land use (see Image 2). These maps reveal that much of the Australian continent has already been allocated to a broad range of human land uses, particularly in the area sometimes referred to as the Intensive Land Use Zone of Australia (or ILZ). This band covers south-western Australia, eastern Tasmania, and the eastern seaboard from Cairns to Whyalla.

Elsewhere, though, there is a mix of largely vegetated lands – up to 83 percent of the nation appears uncleared from satellite imagery11 – and as such, several land-use types and tenures could foreseeably be included and designated through conservation legislation by 2030. These types include Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs), public forest, crown lands, lands leased for pastoral purposes (the rangelands in Australia’s interior and north) and even defence lands (which all have biodiversity conservation plans in place). Putting aside any sarcasm that we might have about the creative accounting that beset Australia in the recent global carbon debate, these areas are the best conservation candidates. With International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)-compatible legislation, these could greatly bolster our achievement of 30×30. This would mean that the number of subregions protected could be as high as 276 out of 421 subregions (see Image 2).

However, this leaves the rather complicated question of what to do in the remaining 143 subregions – that is, the highly contested and more populous lands within the ILZ. While the aspirations of the CBD 30×30 are laudable, if we are serious in creating a robust biodiversity future by meeting this (minimum) target, then how might we plan for biodiversity in these 143 IBRA subregions? Where might we find candidates for conservation at scales, large and small? How could such ideas meet the reality of Australia’s landscapes and land-uses, such as our existing agricultural landscapes and cities? And why is this of interest to landscape architecture?

Continental scale conservation candidates – IPAs, public forest, crown land, leaseholds, defence lands.

Image: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

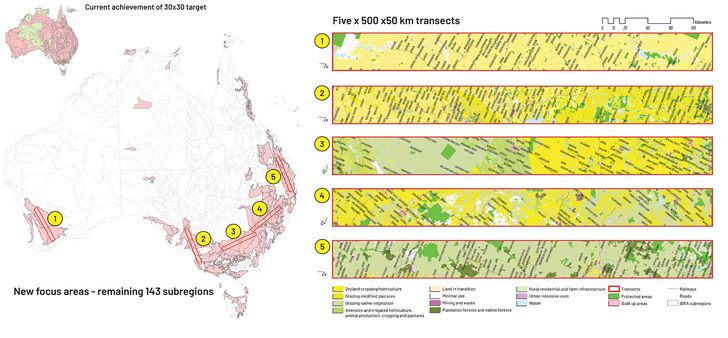

To better understand the scale of this challenge, we took five 500-by-50-kilometre transects and draped them over the Australian landmass.

Transects are often used in the ecological sciences as a way of measuring species diversity and also as a foundational illustrative tool for New Urbanism; while known to landscape architects, transects are rarely used at this scale. Here, transects were used to spatially explore and document specific challenges, as well as to identify several opportunities to achieve the 30×30 target.

From this much-reduced sample area of Australia – essentially that enclosed within the ILZ – we see that the key challenge to achieving the 30×30 target vision is the widespread dominance of existing agricultural and populous urban lands. These areas would be very hard to include as candidates for conservation. In addition, few protected areas already exist – but several opportunities are revealed.

Water catchments and public forests represent lands that substantively have minimal human use and support a vast array of biodiversity that may be with or without formal protection, and these lands offer potential opportunities for as-yet unrecognized conservation candidates (according to the IUCN classification).

Diversity of challenges revealed through transect mapping.

Image: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water and Australian Land Use and Management Classification Version 8.

Rewilding agricultural lands has proved to be a potential step in the right direction, particularly if we embrace a broader philosophical framing that considers more than just primary production. For instance, the United Kingdom has mandated a radical rethink of its agricultural lands, requiring that some be returned to nature, aiming to “support a transformation in the management of 70 percent of our countryside by incentivizing farmers to adopt nature friendly farming practices.” The mandate is funded from 2023 by environmental land management schemes (ELMs) worth £2.4 billion per year.13 This transformation could also include more holistic understandings and practices of flood zone and hydrological protection (connecting back to landscape planning for climate change resilience).

Rewilding the urban means to rethink our cities and suburbs, often hotspots for biodiversity in their own right, so they accommodate biodiversity as inclusive spaces of resident flora and fauna. This focus is already drafted into the planning legislation of many Australian cities, but such legislation can be toothless when confronted with the urban developer-oriented approaches that beset our major urban centres.

The existing patination of protected areas is fragmented. One approach could involve enlarging these areas and reconnecting disparate ones where there is a shortfall of target achievement – pursuant to further investigation with impacted land and stakeholders. Elsewhere, complementary benefits also exist for the provision of additional recreational experiences, urban heat island mitigation and carbon sequestration in areas of rapid urban growth.

Ultimately, for success, we need to significant shift the way we think about and plan for protected areas. We must embrace a broader philosophical framing of landscape planning that recognizes and engages the reality of complex and contested lands and responds to the range of issues and challenges that the lofty 30×30 target demands. Above all, such planning must include the urban areas where most Australians reside. And who better to consider a challenge such as this than landscape architects? The mythic figure of Frederick Law Olmstead – while perhaps better known for New York’s Central Park – was also instrumental to the birth of the first National Park movement all those years ago. We will have to see what happens in the lead-up to 2030 – and if landscape architects will be involved.

1.Michael J. Novacek, Terra: our 100-million-year-old ecosystem – and the threats that now put it at risk (New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2007).

2.Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, IPBES Secretariat, 2019, 12.

3.IUCN, Guidelines for protected area management categories, CNPPA with the assistance of WCMC, IUCN, 1994, 7.

4.Chris Margules and Robert L. Pressey, “Systematic conservation planning,” Nature, vol. 405, no. 6783, May 2000, 243–253.

5.S. Chape et al., “Measuring the extent and effectiveness of protected areas as an indicator for meeting global biodiversity targets,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, vol. 360, no. 1454, March 2005, 443–455

6.Clinton N. Jenkins and Lucas N. Joppa, “Expansion of the global terrestrial protected area system,” Biological Conservation, vol. 142, no. 10, October 2009, 2166–2174.

7.IUCN and UNEP-WCMC, “The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA),” Protected Planet, protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/wdpa (accessed 24 January 2023).

8.Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW), “Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD),” CAPAD 2018 – DCCEEW, environment.gov.au/land/nrs/science/capad/2018 (accessed 27 Jan 2021).

9.High Ambition Coalition (HAC), “HAC Members – HAC for Nature and People,” HAC for Nature and People, hacfornatureandpeople.org/hac-members (accessed 24 January 2023).

10. R.H.G. Jongman and G. Pungetti (eds), Ecological Networks and Greenways: Concept, Design, Implementation, Cambridge Studies in Landscape Ecology (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

11. Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (ABARES) and the Australian Collaborative Land Use and Management Program (ACLUMP), Land use of Australia 2005-06, ABARES, 15 September 2010.

12.ABARES and ACLUMP, Catchment Scale Land Use of Australia – Update December 2020, ABARES, 25 February 2021.

13.Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (United Kingdom), Environmental Improvement Plan 2023, 31 January 2023, 10.

Source

Practice

Published online: 28 May 2023

Words:

Simon Kilbane

Images:

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water and Australian Land Use and Management Classification Version 8.,

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2023