In advance of her presentation at the 2021 Festival of Landscape Architecture in mid-October, Makhzoumi spoke with Landscape Australia editor Emily Wong about learning from vernacular landscapes, restoring human dignity through landscape design and the importance of human-based approaches to ecological planning and conservation.

Emily Wong: Your work intersects landscape, human rights and democracy. Where did your interest in these issues begin and have there been key moments or experiences in your life and career that have shaped this particular focus?

Jala Makhzoumi: In fact, I was not at all a political person. I grew up in Iraq, which has a totalitarian regime and so while there I had steered away from political issues. But this changed when I arrived in Lebanon in 2001, which has much more of a vocal local community because of the freedom of press. One of the sites that I fell in love with there was a nature pocket, [the Dalieh of Raouche], the last remaining vestige of nature in the city and a place that was inclusive of everyone. Following the civil war in Lebanon in the 1990s and with the [subsequent] neoliberal taking over of the city, many of the city’s spaces, which had before been inclusive spaces for everyone, suddenly became inaccessible. The city center became gentrified and gated and the only open space where people could now go to congregate, meet and enjoy nature was really the Mediterranean sea, the Beirut Corniche [a seaside promenade], the waterfront, and thenature pocket of the Dalieh of Raouche. So I vowed that if ever this site was threatened in any way, I would take to the streets – and that’s exactly what happened. The site was purchased illegally and through corruption, and in 2013 the area was fenced off by the contractor for the start of development – and that is when I started my activism. It was in fact, because of landscape – because landscape is the fabric for the practice of citizenship – that I joined other activist to protest the privatization of Dalieh. And so it was landscape that pushed me to activism.

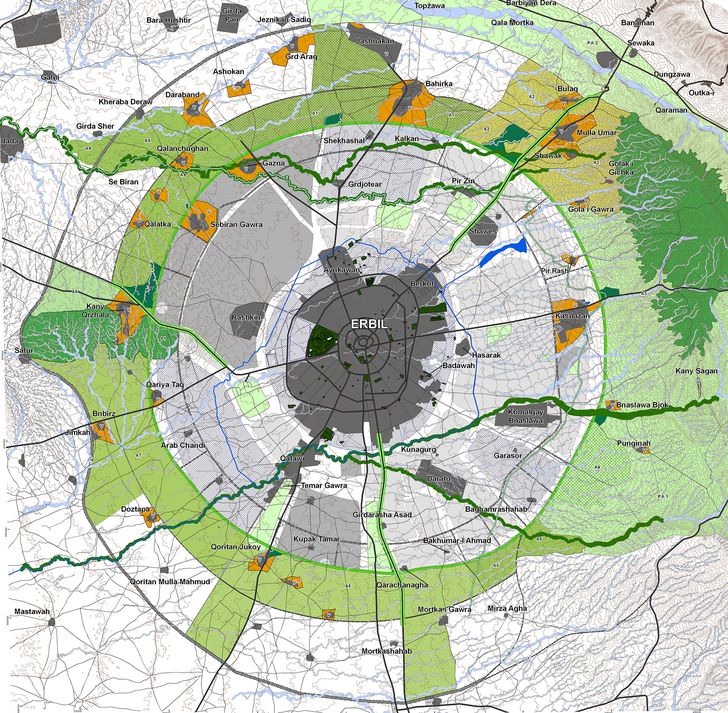

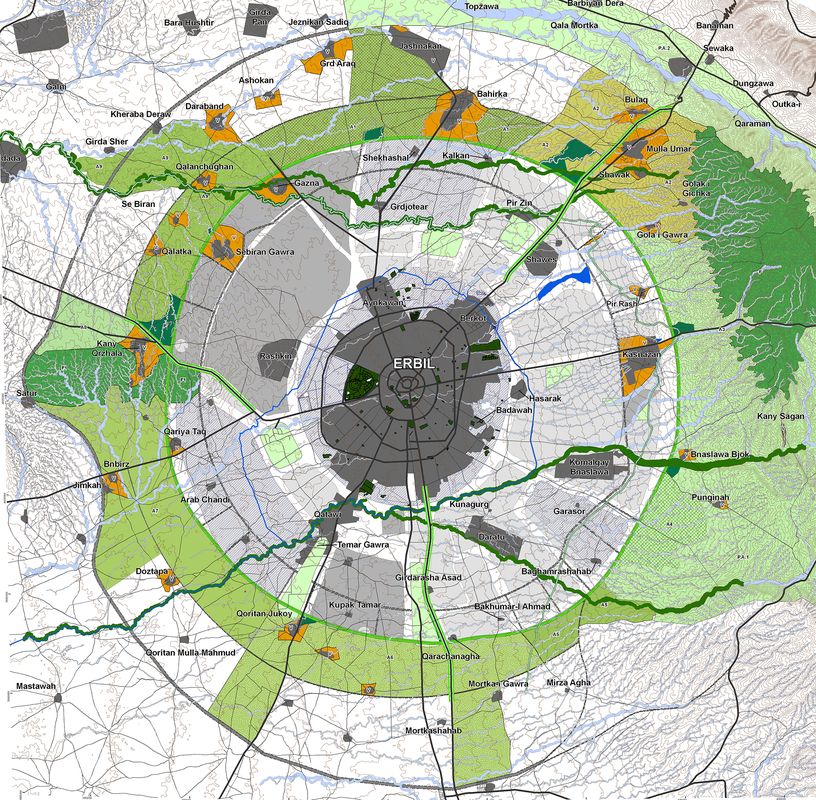

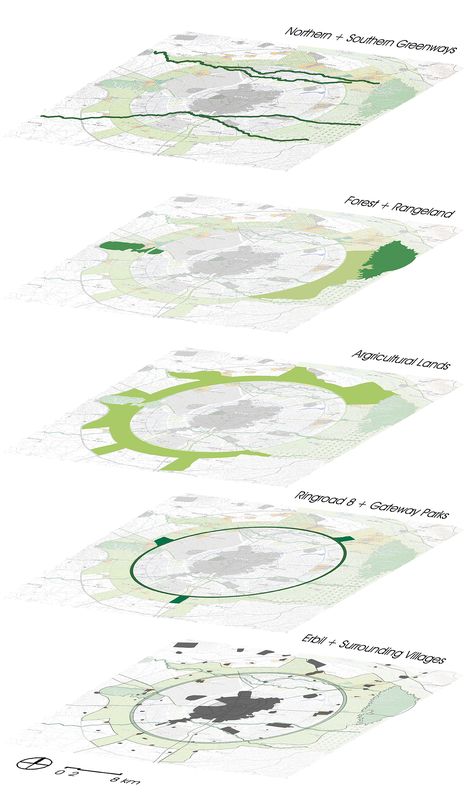

The Erbil Inner Green Belt master plan led by Khatib & Alami Consolidated Engineering with Jala Makhzoumi as landscape consultant proposes a holistic, ecological vision for Erbil, Iraq that celebrates Kurdish rural heritage and agricultural, pastoral and village life.

Image: Khatib & Alami Consolidated Engineering and Jala Makhzoumi

The Erbil Inner Green Belt project proposes the creation of key nature protection areas in the greenbelt and offers alternative livelihoods to local villages.

Image: Khatib & Alami Consolidated Engineering and Jala Makhzoumi

You’ve spoken about landscapes that support human existence and landscapes that support human dignity. Could you elaborate on these ideas in relation to a key project?

All of these concepts evolved from practice, from real life – this is the beauty of landscape. , I became aware of the link between human existence and human dignity in the aftermath of the war between Israel and Lebanon in 2006. During the war there was incredible devastation, extensive bombing in southern Lebanon – and of course, after the war and the bombing stopped, many agencies came in to fund what they then called “reconstruction,” [a term] which I refused at the time, preferring “recovery.” Since then, people have increasingly been using [the term] “recovery,” because the process is not about the building of property, but rather about the mending of lives that have been disrupted and shattered and restoring the dignity that has been compromised. Because when your whole existence is destroyed, the fields where you go to plant, the coast where you used to fish and swim is destroyed and your livelihoods are gone, there is no dignity left. So existence and dignity are very closely intertwined in the post-war conditions. I think landscape is unique in bridging both people and nature, culture and place and so in 2006 we held a landscape studio in the war-shattered community of El Qlieleh, a village in southern Lebanon, and we tried to see whether we could as landscape architects contribute to the village’s recovery, to restore the community’s dignity and inhabitants’ pride in their culture and surroundings, and the landscape that they valued. And so this, for me, was really when those issues all came together.

At El Qlieleh in southern Lebanon, a student landscape studio run by Jala Makhzoumi at the American University of Beirut used research and design to declare the beach an IUCN (International Union of Conservation Nature) community-managed and protected nature site.

Image: courtesy Jala Makhzoumi

You’ve used the phrase “humanizing conservation” to describe your approach and your work takes a human-centered, participatory and interdisciplinary approach to designing the landscape.

People love nature, of course it is in us, but when authorities and state planning [do their work] everything tends to be depersonalized. It becomes very top-heavy and impersonal because they look at the landscape through a two-dimensional property map,a cadastre. First of all a plan, which is an abstraction, is imposed on the people. It becomes the tool for dealing with nature. Secondly, the way ideas are communicated to the community makes it very difficult for people to understand. Biodiversity, for example, is an incredible concept, but if you try to talk to a farmer in a village in the mountains using the term “biodiversity,” it’s too abstract, even [the term] “ecosystem” is too abstract. What is an ecosystem and how do you communicate this? But, thinking and working through landscape is very different, because he can see, he can feel, he lives it, landscape sustains his livelihood. So a landscape framing of a project – not just in nature conservation but in any development project – shapes your own thinking and makes the concepts you’re trying to communicate tangible and legible.

Farmers are much better nature conservationists than we, landscape architects, are, because for them it is a necessity. They have to protect the resources they have and celebrate them, it is their life and livelihood. Look at what they’ve done for centuries, for millennia, in my part of the world – it’s a very old landscape and it’s incredible how much you can learn and how much you can be inspired. Then you, [as a landscape architect] in turn, reflect this back to the communities, showing them how unique their [cultural and agricultural] practices are and how wonderful what they have been doing is. This is very important [in order] to overcome the colonial legacy that denigrates everything that is local, that is vernacular, that is everyday practice, in favour of what is Western and what has been imposed in cities. This legacy is really problematic and permeates all of society, both urban and rural – but why should it be so? A landscape framing that humanizes nature conservation, development and environmental concerns is one way of tackling this colonial legacy, because you do two things. First, as a designer and professional, you look at the landscape as a whole, as a system. And at the same time, you empower local communities, because you tell them how amazing what they’ve been doing is and how incredible their cultural landscapes are.

This also relates to the idea of living heritages which you talk about, as a bottom-up approach that integrates nature and culture, allows for change and where the emphasis is placed on everyday values and uses, rather than “high” values imposed from outside. How do you situate this approach in terms of contemporary challenges, like climate change?

In terms of the global issues we’re faced with today – post-colonial national governments continue, in much of the Middle East, with the engineering techno-centric approach to dealing with everything, with development in general. How do they deal with water resources? This is a major issue in many parts of the world. They deal with it by channelizing rivers, by building large dams. But why build large dams when this valley and theriparian landscape have been managed so efficiently for centuries? Yet they come, they construct a dam, they wipe out a whole ecosystem, they displace communities – and the dam doesn’t even work. This pattern happens everywhere, yet they continue with it. Local communities in Lebanon continue to battle plans for the Bisri Dam [to be built along the Bisri River in southern Lebanon]. For once, the protests against the dam and national protests against government corruption came together, but again, you see this approach that is top-heavy, that is technocentric, rather than being inspired and driven not just by nature, but by local cultures and how they have been dealing with landscape resources. Instead of a dam, they could have easily managed the water with smaller projects and better maintenance.

Another problem, is prioritizing of the national capital that receives the largest share of national financial resources – you find this throughout the developing world again, because nation states were established and bounded and somewhere in the middle the capital city was located. This capital city suddenly became the focus of development, of attention, of education and health, while the rural peripheries were left and forgotten. The real lessons for us, as landscape architects, are very much in these larger rural peripheries because this is where the traditional practices and their legacies are rooted. Vernacular landscapes offer incredible lesson for the global crisis we are experiencing because they use resources efficiently and sustainably and are responsive to what nature can offer and what nature’s limitations are. Landscape is the embodiment of this perspective, of more sustainable, culturally rooted practices, rather than an imposed technocentric, abstracted approach to managing resources.

A vernacular landscape in southern Lebabnon capitalizes on the humidity and fertile soil of a seasonal watercourse for crop planting.

Image: Jala Makhzoumi

A rainwater harvesting reservoir in a village in southern Lebanon has been filled up in order to create a municipal “park.”

Image: Jala Makhzoumi

You’ve worked in various contexts with your location often determined by circumstances beyond your control. What impact has this had in terms of how you approach your work?

It’s had many impacts – I grew up in Iraq for most of my life. Iraq is very, very different[from Lebanon] it is a landlocked country, it has two big rivers and an incredibly diverse landscape. Lebanon also has an incredibly diverse landscape, but Lebanon is a much smaller country. So when I moved from the predominantly arid landscape in Iraq to Cyprus, inthe Mediterranean, the contrastwas big; two completely different biomes, two different ecosystems and two very different cultures. So imagine that you honed in on landscape and ecosystems [as an area of research and practice] and suddenly here are two living examples of landscapes and natures. This is the best lesson anyone can hope for. It was not easy because I had to learn about the Mediterranean ecosystem. I was not familiar with the traditional vernacular practices in the Mediterranean, I was instead familiar with the ones in Iraq. But then when you think about it and intellectualize what’s happening, you find the two contexts are not so different. For example, in Iraq, date palms,what I call structure planting, create a high canopy. The winters in arid regions are very cold, so local communities plant citrus fruits under the palms, it functions almost like a greenhouse allowing the winter sun in but screening the hot summer sun. So you have a multifunctional landscape – permaculture, if you want to call it that. Then you go to the Mediterranean and it’s not very different. Olives and carob trees are the structure planting, and they are intercropped with arable farming, pastoral uses and so on. So you see the efficient use of land, mainly fertile soil, and water in both cases, is the essence of sustainability. And so you start to understand the working of the landscape and how it evolved to be part nature and part culture.

You’ve been very clear that research, practice and teaching are all equally important to you – and have been throughout your career. How do you operate between the studio space and the university and how do they fit together?

I’ll give you an example rather than talking in the abstract. For many years in Iraq, I was teaching there, teaching architects not landscape architects. I became increasingly interested – I’m talking the 70s, so really a very long time ago – in the overlap of ecology and landscape, and what is ecological landscape? In Iraq, I found many examples of ecological landscape there in vernacular settlements, in vernacular practices. But how do you teach students to do ecological design? I didn’t know. For the first 15 years I taught there, I researched, I looked and I spoke, I didn’t quite know the answer. Then when I left Iraq in 1990, I was engaged in a professional project for a large tourist project in Cyprus. It was my role as a professional there that helped me develop the methodology of ecological landscape design which I later published in my first book, Ecological Landscape Design and Planning, with Gloria Pungetti. This methodology was developed by retracing my own design thinking and approach to that project in Cyprus. Graduate students in urban and landscape design at the American University of Beirutare now applying this methodological framework on a range of topics to address the same issues we have been talking about, namely culturally rooted and humanized approaches to design, planning and development. So you see how everything is connected. I had to practice to understand, because landscape architecture is about professional practice. I had to write, because by writing you reflect, you rethink, you read, you bring together and you make sense of your ideas. And then, when you teach, you explain and and test both. I don’t know how I could survive without all three of them. At times it’s overwhelming. I have reduced my teaching at the AUB, but continue to value my academic involvement.

Jala Makhzoumi is a keynote speaker at the 2021 Festival of Landscape Architecture: Spectacle and Collapse which will take place online and in Perth from 13 to 16 October 2021. To view the festival program and register, go here.