The buzz and lure of innovation are ever-present, yet innovation has never been more needed than now. A sense of urgency has arisen in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic across all social and economic sectors. The vulnerability of complex associations between professions has been highlighted, particularly as we grapple with ways to readjust across the construction industry. The effects of disrupted supply chains, and skill and labour shortages, are felt at the local, regional, national and international scales. While the experience has also emphasized differences between organizations, what continues to remain common is the underlying quest to learn from the disruptions and be better equipped to adapt to sudden changes in the future. Livelihoods and legacies depend on it.

At such times of crisis, innovation is sought by organizations, in order to adapt. So, what does it actually mean to innovate? The answer may lie on the greater playing field.

Innovation can be associated with the concept of “creative destruction,” which was introduced by Austrian-born economist Joseph Schumpeter in response to World War II. Creative destruction refers to the process of attrition and renewal in the market that results from major events or economic crisis. Advances in technology are typically used to increase productivity and efficiency as a means of maximizing value. Further concepts of “lean thinking” (a model that seeks to deliver greater social benefits while reducing waste) have also come to influence a wide number of sectors, including manufacturing, management, business and healthcare. Within the built environment industries, multiple innovations have been occurring simultaneously since the 1990s through advances in digital technologies. The disciplines of engineering, architecture and construction have since been engaging in robust discourse and practice around innovation as a topic and a goal. By the early 2000s, these developments manifested with Building Information Modelling (BIM), which is now shaping the industry.

Yet, landscape architecture has been lagging in this discourse and practice. Since 2015, increasing attention has been given in scholarly and professional debate to the need for landscape architecture to address the innovation gap with allied professions. The gap is due to a lack in three main areas: definition, data and research.

First, innovation is all too commonly applied in loose terms as a descriptor to invoke novelty, creativity and originality in the profiles of organizations, project briefs or reviews of award-winning work. Yet, in wider discourse, innovation encompasses the systematic generation, development and implementation of new ideas, behaviours1 and tools. These combine to alter processes, including design, management and/or construction processes; BIM is doing this across all disciplines.

The second gap is in the lack of reliable data to inform small-to-medium-sized organizations in the profession. These organizations make up the majority, and the lack of data leaves them vulnerable when making decisions during volatile periods. In contrast, large multidisciplinary organizations have distinct advantages in accessing data to precisely gauge market directions and inform decisions around investment in new and innovative technologies, skills and processes.

Third, a gap in research leaves the profession exposed within the technological, organizational and environmental contexts of innovation. This is significant. My recent research on BIM indicates that the environment context is a major influence on organization uptake. The environment factors include market demand and competition, corporate positioning, role of professional associations and government policies.2

The COVID-19 crisis provides an opportunity to begin articulating and debating what it means for landscape architecture to innovate. There are many avenues for exploration. New skills and roles are needed to meet changing practices. For instance, landscape architecture-trained BIM managers are needed to influence the direction of projects in powerful ways – for example, by acting as design gatekeepers to retain the integrity of landscape values throughout a project’s

life cycle.

Further, the impacts of innovative tools and processes need to be collected, measured and openly shared. This would help with identifying inhibiting and enabling factors, beneficial outcomes and lessons learned. Professional associations are important in empowering members with information and networks in relation to the broader playing field, as exemplified by the UK Landscape Institute’s approach to BIM, with workshops, publications and advocacy. The Asia-Australia region is crying out for such direction.

In addition, the increasing demand for data is evident among competitors in engineering and architecture in larger multidisciplinary organizations. Here, data is integrated in evidence-based design and harnessed to enable performance analysts to better define value.

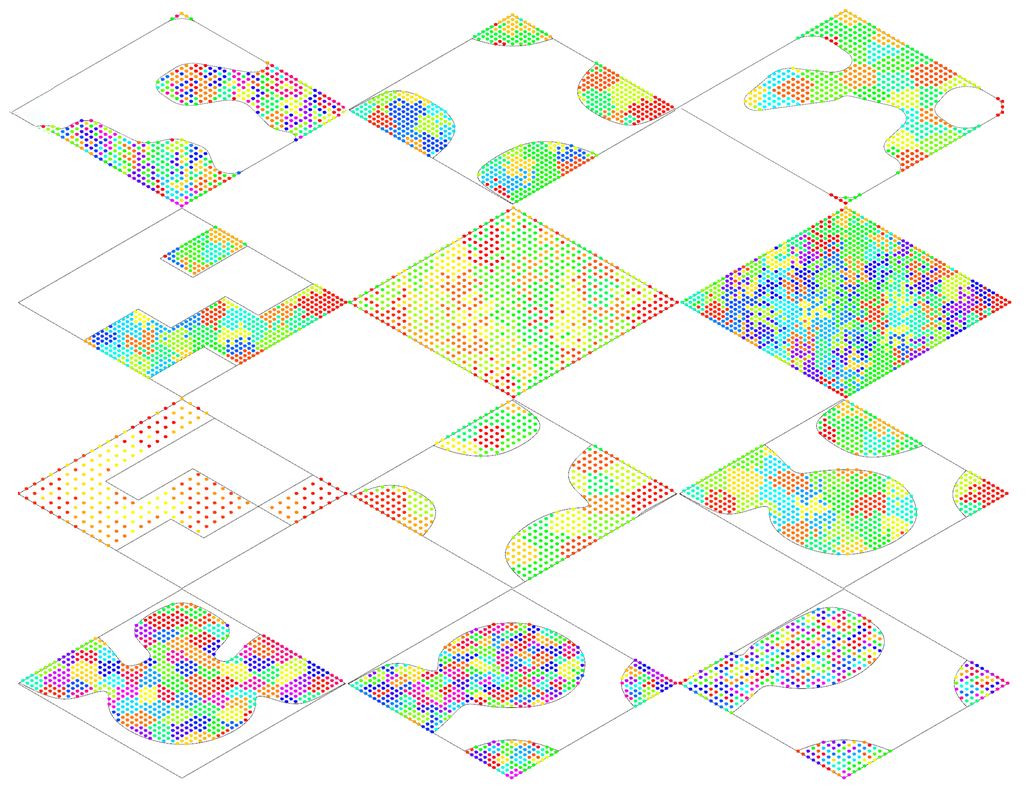

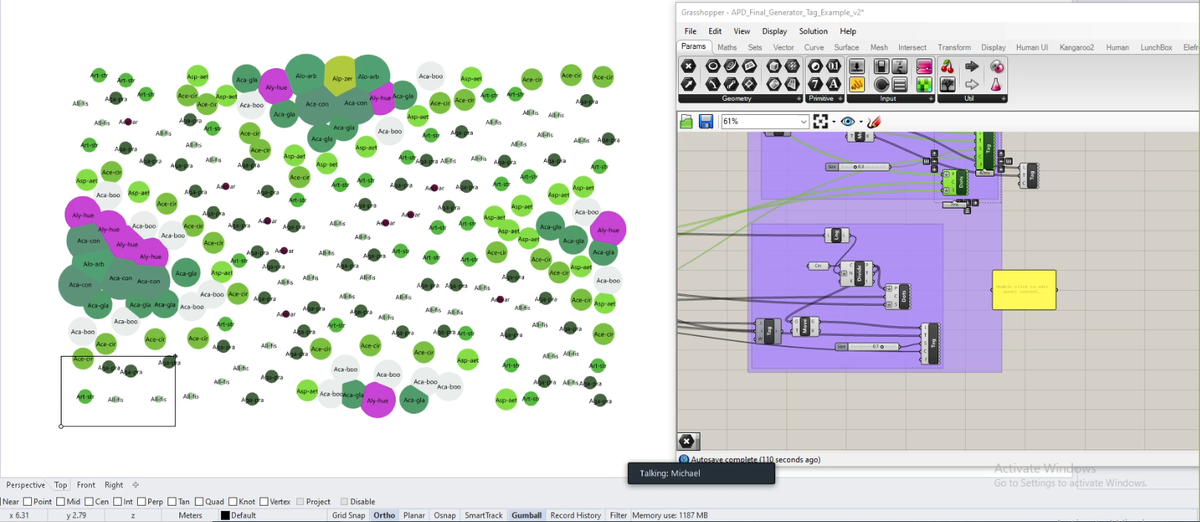

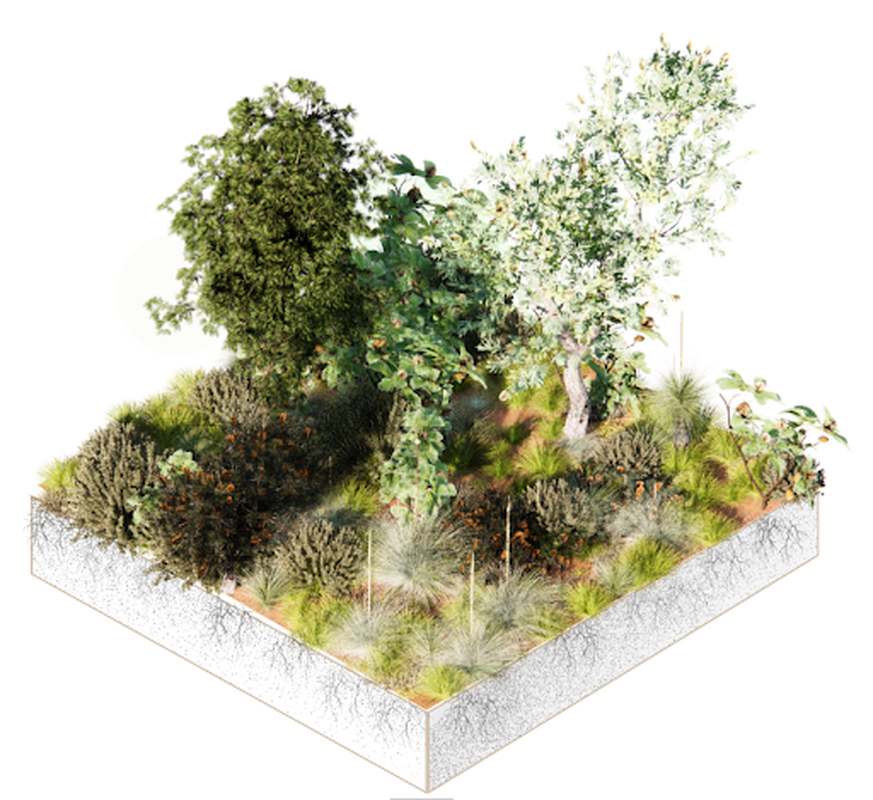

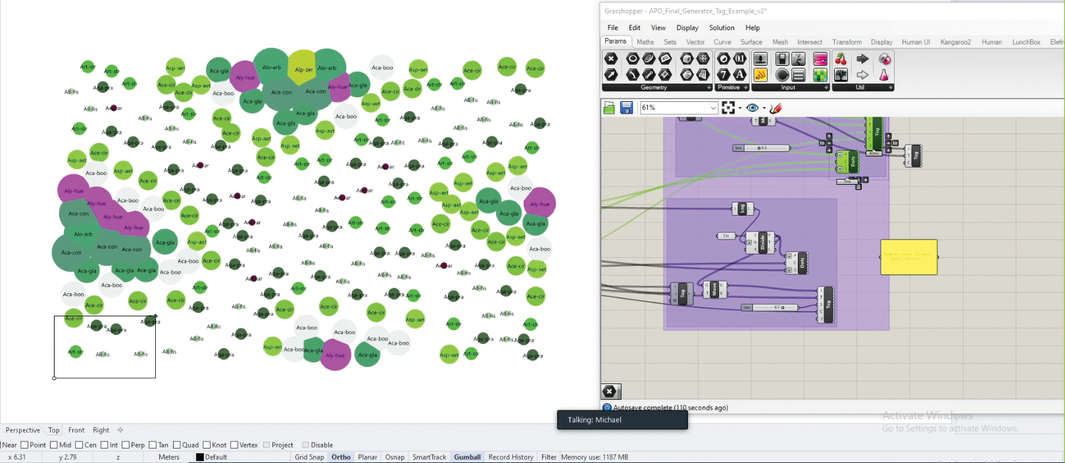

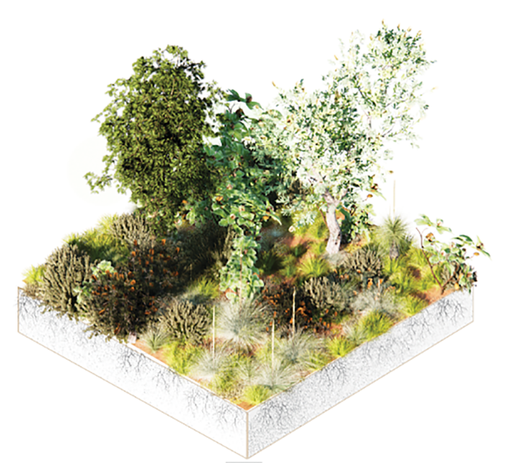

Other areas of innovation include dealing with the complexity of design with living systems. In addition to integrating wider sources of data, practitioners are now simulating agent-based models to achieve complex, multi-layered plantings at larger scales. All of these approaches can help landscape architects to gain competitive advantage in a market that is dominated by engineering and architecture.

Lastly, a practice-focused forum on the topic of BIM as a form of innovation might offer a starting point to share ideas and methods in the public arena. Such a platform could bolster the profession’s capacity to understand and work with innovation, as society and industry rapidly shift beneath our feet. BIM is yet to be proven as the panacea for the industry’s ailments, but major inroads have been paved. Landscape architecture can only benefit in looking to itself for “creative destruction” – that is, to uncover and destroy redundancies in order to renew.

1. Fariborz Damanpour, “Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators,” The Academy of Management Journal,

vol 34 no 3, 1991, 555–90.

2. The author is currently in the final stages of PhD research on the topic of “Transitional strategies of landscape architecture practices in the digital realm” at the University of Melbourne. The research is due to be published in 2022.

Source

Practice

Published online: 5 Jul 2022

Words:

Jela Ivankovic-Waters

Images:

Michael G. White/Hassell

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2022