In 2013, after more than a decade of living, studying and working in Melbourne, I had become increasingly haunted by the biologically and psychologically rich contours of Queensland’s Wet Tropics, where I was raised. After previous promising but faltering attempts to develop a photographic project in the region, I set aside a month within which to reabsorb myself in the landscape, via the slow process necessitated by the unwieldy 8x10-inch view camera I was using.

This immersion, while reinvigorating to my visual and ecological curiosity, was underpinned by a forlorn sense of the impacts of climate change that were starting to reveal their influence in the region. The Great Barrier Reef had recently suffered unprecedented coral bleaching damage and the possibility of a wave of extinctions, particularly in the temperate refugia of the region’s highland rainforests, already appeared increasingly likely. This “slow violence”1 was overlaid upon a landscape where the disruption of Indigenous land-management systems by a century of extractive settler-colonialism had already pushed many rare and ancient ecosystems to the brink of extinction. Approaching the landscape in a manner redolent of intimate portraiture, I was under no illusions about the capacity of my photographs to affect any kind of political change. It was soon apparent, nonetheless, that the works were beginning to represent reliquaries for a landscape that, despite the attempts at protection and restoration it had been afforded over recent decades, continued to unravel in myriad ways.

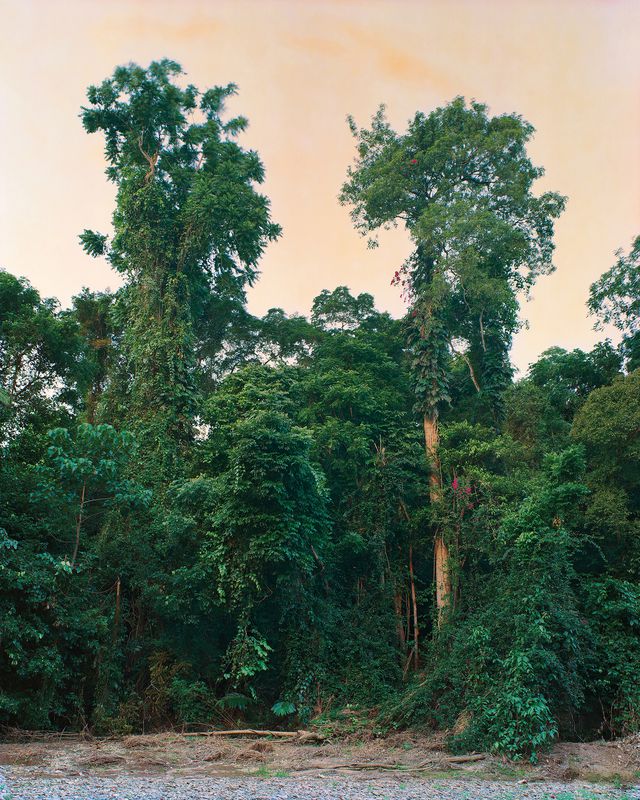

Freshwater Creek (Djabugay Country), 2018. Complex mesophyll rainforest growing on alluvial soils lining the banks of Freshwater Creek in Redlynch Valley, Queensland. The immediate streamside topography here is always shifting as sediments are alternately deposited then flushed away again in successive floods. The dominant emergent canopy trees are ivory mahogany (Dysoxylum gaudichaudianum) and milky pine (Alstonia scholaris), high upon which the unmistakable pink bracts of an ambitious bougainvillea vine are visible here.

Image: Matthew Stanton

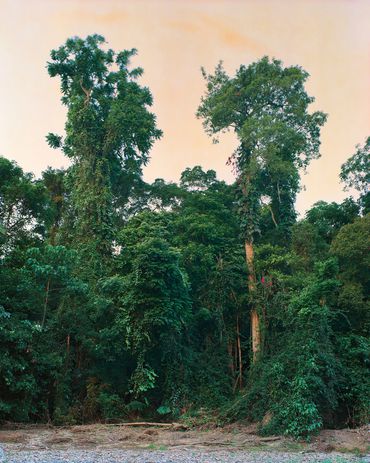

Mulgrave River (Yirrganydji and Yidinji Country), 2013. One of the major watercourses in the region that has changed its course a number of times throughout the Holocene period. The stretch of river pictured is predominately lined with water gums (Tristaniopsis exiliflora), an extremely tenacious species that has, of recent years, become vulnerable to the exotic myrtle rust pathogen.

Image: Matthew Stanton

The Deep North series interweaves conceptual threads that twine and converge around anthropocentric themes, as positioned against the vastness of geological time scales. An important aspect of the series is its examination of the role of humans as useful ecological agents in relationship to themes of legacy, posterity and inheritance. The question of how we might harness a nuanced understanding of the processes at play within different ecosystems to protect and maintain them became a significant touchstone as the series evolved. This interest extended to the critical roles we, as a species, are required to play in guiding the regeneration of complex ecological processes in landscapes that would otherwise stall or unravel without further human intervention.

Mum (Ngadjonji Country), 2015. My mother Karen sitting at her favourite location where a rainforest stream pools at Wooroonooran (meaning Black Rock). She and my father have worked for three decades to replant and regenerate 160 acres of previously denuded dairy property in this very high-rainfall zone within an important refugial area where complex tropical rainforest had previously persisted over successive ice ages. Platypi can be seen swimming in the pool early in the morning.

Image: Matthew Stanton

African Tulip – Spathodea campanulata (Djabugay Country), 2007. An exotic ornamental species from Africa that is highly invasive in gullies, watercourses and areas of disturbed rainforest, where its aggressive regeneration by seed and sucker will allow it to rapidly out-compete indigenous species. The nectar and pollen it produces also contain toxins that are harmful to insects and particularly inimical to native stingless bees.

Image: Matthew Stanton

The first exposure I made in 2013 depicts the forlorn remnants of a large hoop pine forest adjacent to my childhood home that had been planted on the former site of a Chinese gold mining camp by a Djabugay man named Wurrmbul around the late 1920s. Wurrmbul had been born into Djabugay tribal life in the surrounding mountain country at the turn of the twentieth century, but as a young man had lived with his mother with a local settler family. Later, he was employed for many years by a local farming family, for whom he cultivated the forest as a future timber resource. For 80 years, the forest that Wurrmbul planted remained unharvested, reaching great stature and becoming a playground for local children, who were equally enticed and haunted by it. Around 1985, my parents and I accompanied Wurrmbul, by then an elderly man with failing eyesight, back to the forest for his first visit in several decades. His obvious delight that day, at finding himself amidst the sounds and smells of the landscape he had propagated so many years earlier, has long lingered with me as a reminder of the concentric circles of memory that cut across one another within a landscape. As a dominant rainforest species with many mature plantations, the hoop pine’s potential to support the regeneration of diverse rainforest ecosystems beneath their canopy, when encouraged, is significant. Sadly, however, Wurrmbul’s forest was cleared in around 2010 in order to make way for a long-slated “eco resort” that still remains unbuilt.

Devil’s Leap (Djabugay Country), 2018. Devil’s Leap along Freshwater Creek in Redlynch Valley was, for many decades, the epicentre of adolescent social life in the area. In recent years, it has been largely abandoned, but remains as a kind of melancholy monument to time lived and shared within the landscape.

Image: Matthew Stanton

The Last of Wurrmbul Banning’s Hoop Pines (Djabugay Country), 2013. The forlorn remnants of a previously extensive hoop pine (Araucaria cunninghamii) forest that was planted in the 1920s by Wurrmbul, a Djabugay man and inhabitant of the surrounding mountain area. The forest was cleared a decade ago to make way for an “eco resort” that remains, thus far, unbuilt.

Image: Matthew Stanton

Mareeba (Muluridji Country), 2015. The ubiquitous and frequently outrageous Bougainvillea glabra from South America, which is a common urban ornamental shrub throughout the Wet Tropics. While not a particularly invasive species in the region, it can sometimes be seen scaling the canopy near the exposed edges of local rainforests.

Image: Matthew Stanton

Another significant element of the series emerged in 2018, when I accompanied the Djunbunji land and sea rangers for a week as they worked to manage the Gunggandji-Mandingalbay Yidinji native title lands south of Cairns. My brother and father, both landscape ecologists, had been collaborating with the ranger group over a number of years to help develop and monitor their land management program; of particular priority was the maintenance of “Bloodwood Plains,” a pristine grassy coastal woodland landscape of great ecological and cultural significance. Situated in a high-rainfall zone upon a sand plain between the shores of the Coral Sea and the rainforest-draped Malbon Thompson Range, the area has been shaped by anthropogenic fire and cultural practice through millennia of meticulous land stewardship. Traditional fire management has never been withdrawn from Bloodwood Plains, which maintains its status as a biodiverse grassy sclerophyllous ecosystem, unlike many other areas in the Wet Tropics that have undergone irreversible transition to closed forest through the exclusion of fire. The strategic timing of the burns has recently been shifted to maximize the vigour of the grassy understorey and suppress invasive weeds and forbs that threaten the integrity of this relict vegetation community.

Deep North remains an ongoing project, the scope of which continues to develop over time. Its open-ended nature allows significant flex to accommodate the emergence of new elements and shifting frameworks of understanding.

The artist respectfully acknowledges the Gunggandji-Mandingalbay Yidinji people who welcomed him upon the traditional lands to which they hold native title to produce the images of the Djubunji Land and Sea Rangers conducting their traditional fire-management practices. He extends his gratitude to the Mandingalbay Yidinji Aboriginal Corporation for their help and collaboration in the production of theseimages and pays his respects to Gunggandji-Mandingalbay Yidinji Elders past and present.

1. In his 2011 book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Rob Nixon refers to the devastation wrought by climate change, deforestation and environmental pollution that unfolds gradually and often imperceptibly as a “slow violence,” the greatest effects of which are experienced by the poor and the disempowered.

Source

Practice

Published online: 23 Sep 2021

Words:

Matthew Stanton

Images:

Matthew Stanton

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2021