Rosie Halsmith – Could you tell me a bit about yourself, and how you came to be a landscape architect?

Fiona Harrisson – I came to landscape architecture through horticulture. I studied horticulture at the University of Melbourne’s Burnley campus. The great thing about Burnley was that each student had a garden plot where they could grow plants. It was an amazing place to be. But I came out of there and thought to myself, “I’m never going to be a scientist.” It just didn’t light my fire.

After studying horticulture, I studied landscape architecture and then started [practising] in Melbourne. After about seven years, I completed the Metropolis Masters in Architecture and Urban Culture at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya in Barcelona and then started teaching in the landscape architecture program at RMIT. At the moment, I’m doing a creative practice PhD.

Fiona Harrisson, senior lecturer in landscape architecture at RMIT University.

How do you define biodiversity?

I’m less interested in defining biodiversity as a “thing.” My interest in biodiversity has invited me to see the world from an other-than-human perspective. We can’t see the world just through the human lens anymore, and we probably never should have.

This shift in perspective is a practice I’m exploring in the PhD. For me, it will probably be a lifelong practice. I’m interested in how I can invite students to engage with this as a practice, as well.

Could you speak about your work in the Avoca Design Studios from 2009 to 2010 with RMIT students and the community of Avoca?

The RMIT studio was invited to take part by scholar and artist Lyndal Jones, who was running a 10-year art project in the small town of Avoca in the central highlands of Victoria. In the Avoca Design Studios, I brought the garden into the discipline of landscape architecture by using it as a scalable way for students to understand and respond to larger environmental concerns of climate change.

To begin, I put an advertisement in the paper – a call-out for interested community members to have students work in their garden. Then, the studio travelled up to Avoca to look at potential projects.

In those initial meetings with community members, we realized that people might not know what a landscape architect is and does. After initial conversations, the students and I agreed on the gardens that would be selected. In consultation with the students, I renegotiated the brief with community members. We said, for example, “We’ll do your garden if you’ll accept that we’ll do it without irrigation – we want to work with the rainfall.” That project then became interesting for us. From then on, students were in conversation with the clients, working in small groups on a semester-long design and build process.

Fiona Harrisson “micro-weeding” a patch of vegetation. The activity slows down the act of looking.

What impact did this collaborative process have on students’ learning about site and values – and towards a shift in perspective?

For me, the most profound transformations have [come from] experiences in the living world.

When I teach, I prefer to work outside of the classroom, where I’m not the only one who will be responding to the students’ work. I want community to be present, so there can be a conversation that politicizes the design process in the bigger sense.

At Avoca, the community were the experts in their area. The students were obliged to listen – it didn’t mean they had to give the community what they wanted, but they had to take their feedback on board. This studio was about students learning through relationships and being in the world.

In 2021, you worked with RMIT landscape architecture students during Melbourne’s lockdown on a studio named “Microcosmos: A plant’s eye view of the world.” Could you tell me about this project, and the role that other-than-human thinking played in developing students’ understanding of biodiversity values?

I used the idea of “microcosmos” as a way in – this idea that if you understand the small in multiple ways, you can understand the big. The “Microcosmos” studio drew on practices of gardening to inform design.

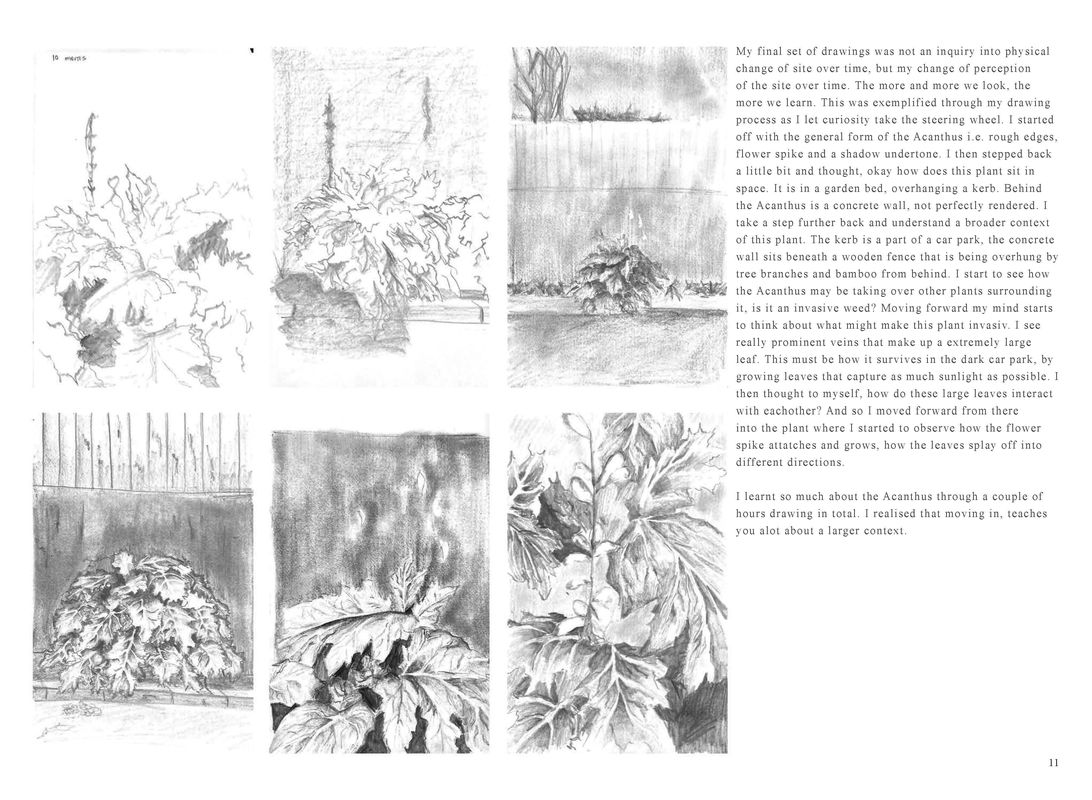

We were working in lockdown, so I asked all students to work in their own place, wherever they were. They were asked to go and find a particular plant that they were interested in. They were then asked to do seven observational drawings showing this plant over time, being attentive to the above- and below-ground relations between plants, animals – specifically insects – and microorganisms.

These drawings were important, as they slowed down the act of looking. While the students were drawing, they were present in the living world. It gave them a frame within which other things could emerge.

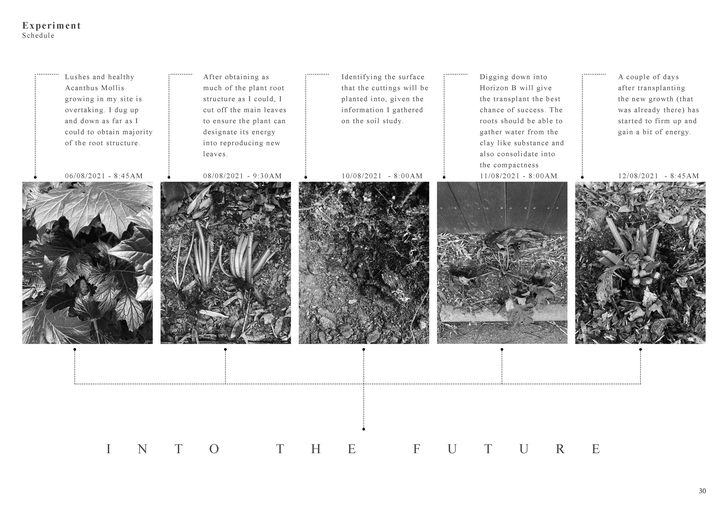

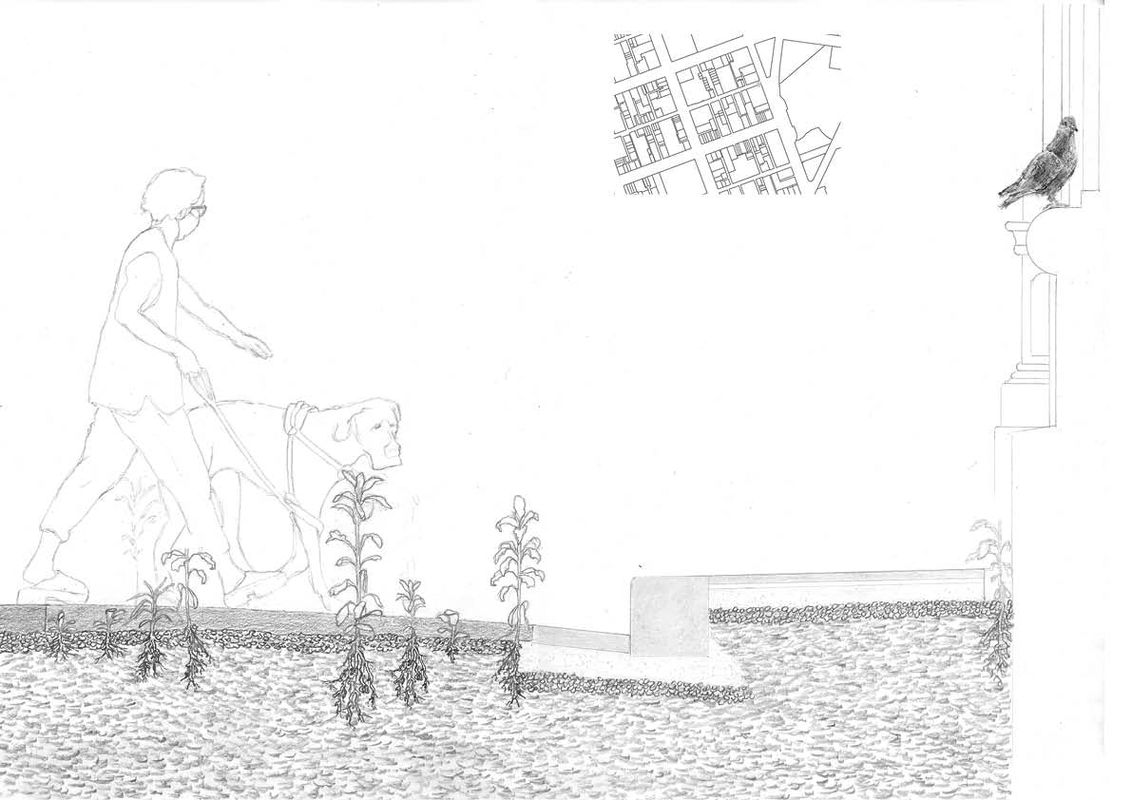

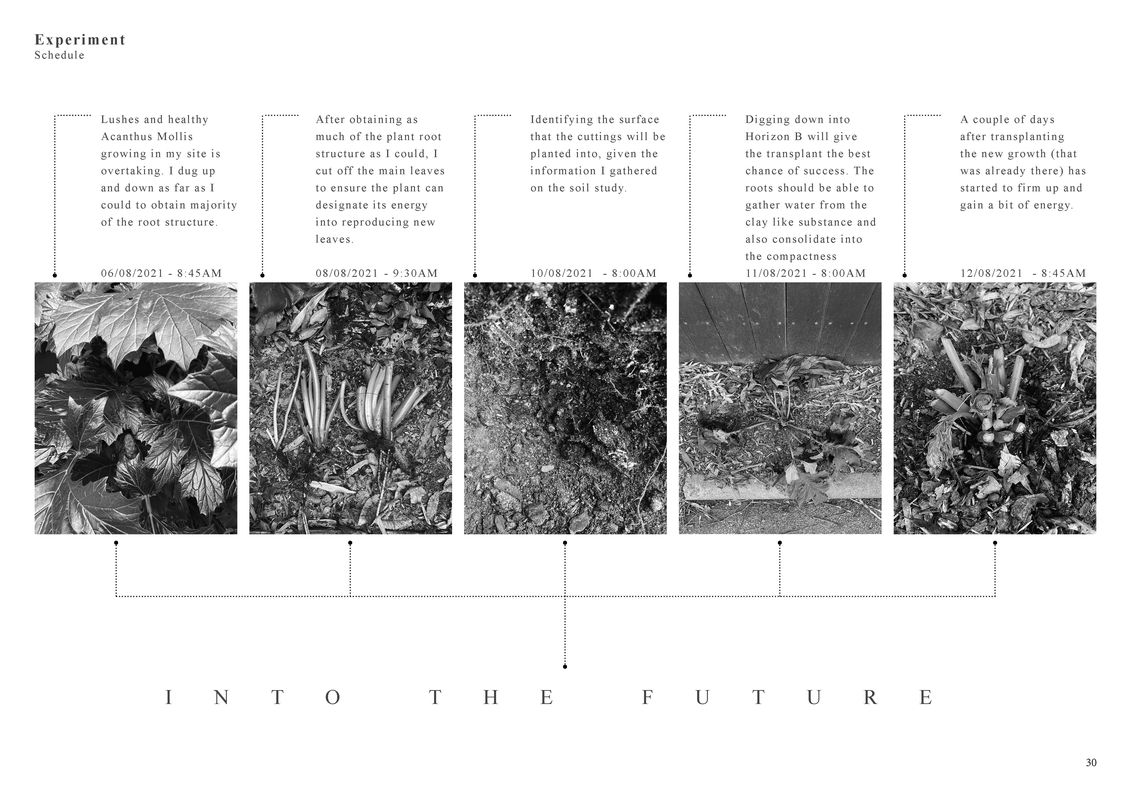

Cody Hooper worked within a weedy patch in a car park, cultivating Acanthus mollis and studying the soil.

Image: Cody Hooper

After completing the drawing exercise, students were asked to do a 1:1 design experiment accompanied by a month-long observation. One student who lived in the inner-city had been drawn to a weedy path in a laneway. This student decided to cultivate this patch, to keep a maximum number of species there. Someone else was testing different ways of planting into a nature strip; someone else did a burning of poa to see what the effect of that was.

Students developed an interest in the living world in a participatory way. From that, they were asked to scale up their thinking to inform a broader design intervention. As a part of this design intervention, students were asked to include processes of implementation and cultivation, over time.

Could you speak to the value of working with the practices and processes of gardening? How has this informed your teaching?

Time is important in a number of ways: time to observe and the time of the cycles of the living world. The garden really obliges the idea that something unfolds over time. Gardening is a practice that is increasingly interesting to draw on in our discipline, because it is attentive and direct. The garden experiment is a way of working directly with the living world.

Source

Practice

Published online: 17 Mar 2022

Words:

Rosie Halsmith

Images:

Cody Hooper,

Sketch by Tim Sterling

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2022