Always an admirer of the Renaissance sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini and curious about his practice, I watched with interest recently a video describing just how he produced perhaps his most famous sculpture, Apollo and Daphne, siting it in a particular room in the Villa Borghese in Rome. Watching and listening, I was struck by the essential aspects of Bernini’s practice that still align with work in the creative fields. He knew his material, selecting his marble blocks from the quarry at Carrara. He knew his site, designing the piece precisely in relation to its space, to be experienced as part of a sequence he choreographed. Before sculpting, he drew and drew and drew to the point where, presumably, he “knew” the piece before it was made, not only in his mind but viscerally, in his hands. To him, the piece was already alive and the paper discarded. An artistic master, he knew his medium in all its dimensions, using his superior knowledge, and his capacities for analysis, imagination and visualization, to support the work of his hands, controlling the entire process from conception to realization, taking incredible risks and extending the reach of his art. For those of us interested in how great work happens, history tells us that beyond artistry, he was also a master practitioner, a ruthless competitor in the creative marketplace who used all his wile to get – and be paid for – the great commissions for which he is known. In a period of flux, political intrigue and high drama, he thrived.

Bernini was like many other great practitioners whose works are known to have transformed our thinking and doing: Frederick Law Olmsted in the United States, who produced his great suburbs, greenways and parks when typhoid and tuberculosis raged and America was in the midst of the Civil War and its devastating aftermath; Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London (his contributions went far beyond the churches and cathedrals he is best known for); Isambard Kingdom Brunel, whose great designs recast the streets, bridges, railways and plumbing of an unhealthy, over-industrialized Great Britain; or Georges-Eugène Haussmann in a chaotic post-Napoleonic Paris. Consider the great works of the modernists that followed the physical devastation and economic ruin of World War II. The list goes on. Each saw what was needed in difficult times and was willing to engage in the wider world that surrounds practice, to argue for and adapt their environments and the way they were made. They had the understanding, the vision and the knowledge, and they fought for and achieved change.

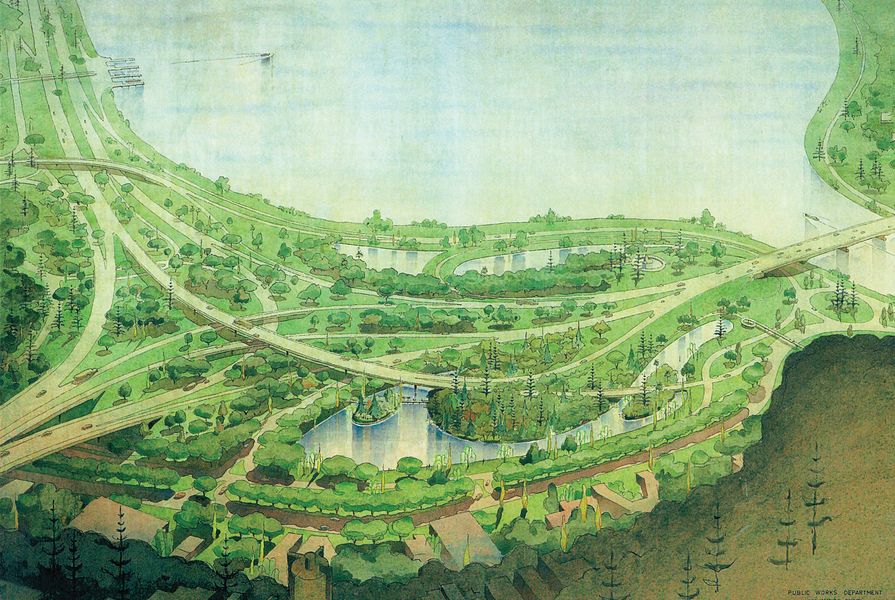

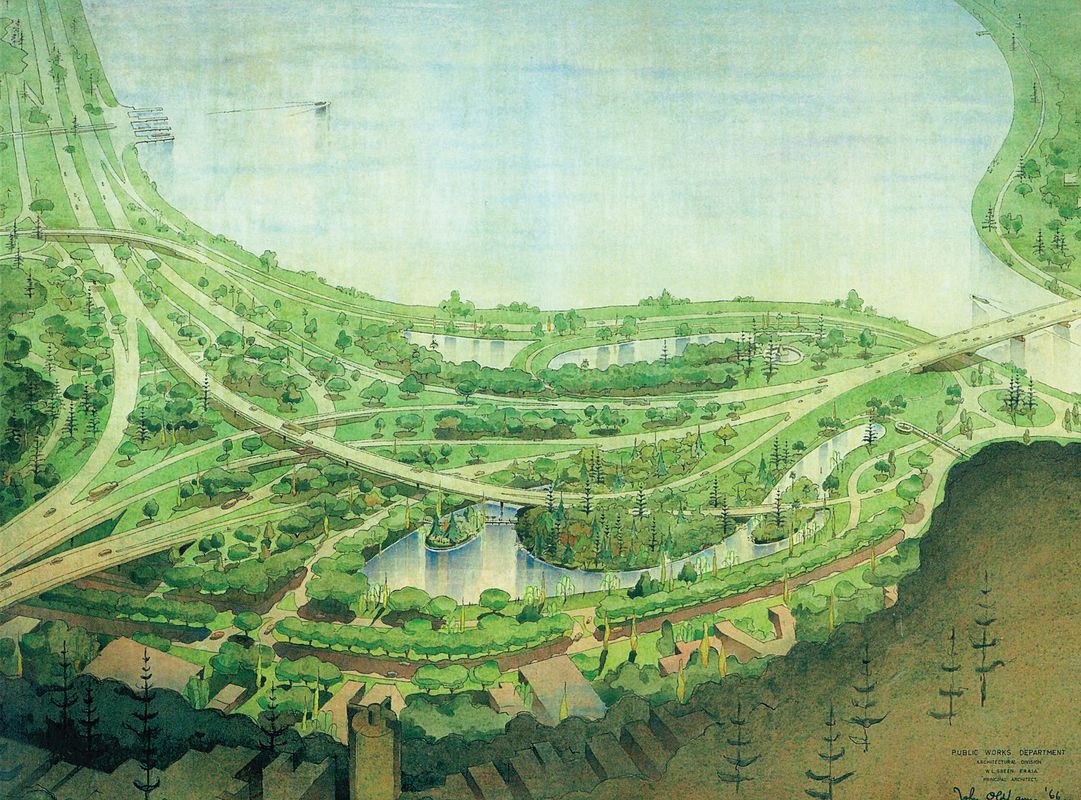

Peter Spooner’s work on the Sydney to Newcastle Expressway (1962–1967) paved the way for collaboration between landscape architects and engineers.

Image: Roads and Maritime Services.

For landscape architects working in Australia in 2020, also a time of drama and flux in the wake of drought, bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic, the question must be whether the profession will survive, whether it will thrive, and if so, how? Like our fellow citizens and professional peers, landscape architects across Australia are asking what kind of working environment they will confront going forward and how they themselves may need to change. They have the basic skills demanded of professionals, but how do they prepare for a new normal – where resources are scant and will be argued over even more than previously, where physical adaptation of our environments will be complex and where professional territories will be hard fought for and challenged? While none of these challenges are new, for the next two or three decades (after a first flush of project funding), they will be exaggerated.

Because of the speed and breadth of their emergence, current circumstances appear unique and difficult to conceptualize. Senior practitioners will recognize major change as cyclical, recalling in our professional lifetimes the major recessions at the turn of the 1970s and the 1990s, and the global financial crisis of 2008, when we learnt the importance of having reserves at hand, of re-focusing practice and of up-skilling. We grew up in families where the Great Depression and the horrors of World War II were part of lived experience. It could even be argued that while landscape architecture had been slow to establish in Australia precisely because of the straitened circumstances that followed World War II, a national focus on infrastructure and suburbanization that largely ignored environmental impacts and social needs spurred the emergence of the profession, in reaction, in the 1960s, along with environmental legislation and planning. In each of these moments of change, there have been individuals who read the circumstances and understood their import, and were agile, willing and able to act. Honing and extending their skills here and abroad, they found ways to use those skills to personal, social and environmental advantage. They repositioned and made the profession’s history.

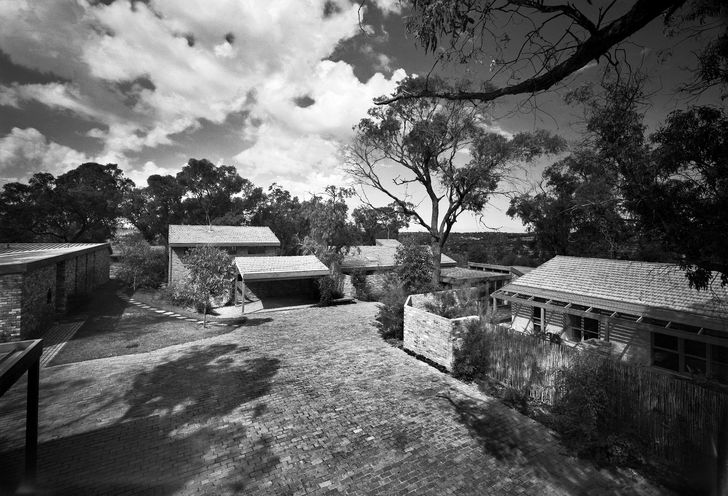

Car crossing Serpentine Dam (1967) in Western Australia by John Oldham.

Image: State Library of Western Australia, 011386D

This is another such moment. Many of us have expected, even predicted, an environmental and economic “adjustment” for some time. Climate change, environmental degradation, social inequality and displacement have been experienced, described and fought over for decades but, until now, proportionate response in Australia has been frustratingly slow. With the environmental, social and economic devastation resulting from the bushfire emergency and the COVID-19 pandemic, change in 2020 has by contrast been dramatic and rapid in ways that have been surprising. With time, some aspects of our lives will change; others will remain the same. Some sectors of activity will shrink and some will grow. How will the profession of landscape architecture respond? Where will it land?

Right now, the profession is in an enviable position. Its core products – open space in all its forms and for all its purposes – have demonstrable and recognized value. After decades of taking a back seat to the market, its core client, government, has reasserted its role as a driver of environmental and social performance. But to capitalize on these circumstances, landscape architecture also needs to adapt and add to its armoury of skills. It needs evidence-based practice, it needs advocacy and it needs experience in governance – all skills it has lacked in the past. It needs to muscle in and be noticed in a crowded professional marketplace and a society flooded with opinion and commentary through social and other media. Our cities and settlements will adapt, but will we?

As a profession with environmental and social health for the long term at its heart, landscape architecture can and should be central to that change, using evidence and advocating for what we know and care about, being where decisions are made and tailoring the profession to fit the times.

Government is already committed. Infrastructure, large and small, will be prioritized; streets will be recast; suburbs will be reinvigorated; urban centres will be remade. New ways to manage open space for environmental risk will be considered. Communities will want to be engaged. All kinds of trades and skills will be supported, in the short term through projects and over longer time frames through education. State and local governments will be at the front line. Do we have the variety of skills – in our big, multidisciplinary firms, in our local and topical specialists, in government and amongst our researchers – to step up and respond? Do we investigate, understand our work in ways that are defensible and promote it in ways that are relevant? Are we present in the places where decisions happen?

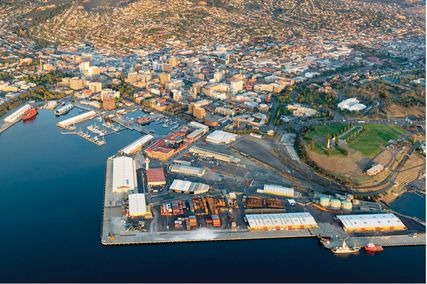

Yurulbin Park by Bruce Mackenzie and Associates (1972–77) is a seminal landscape of native plants.

Image: Peter Bennetts

As an applied science relying largely on the researched science of other disciplines – natural, social and material – we have been slow to develop the credible, discipline-specific research required to provide evidence of the positive difference our methods of practice make. Where are the doctoral students and the research teams that generate that evidence in Australia? At the very least, the last months have demonstrated – through both the bushfires and the pandemic – that it is such evidence that feeds the advocacy, wins the argument and directs the course of action.

How will our working professionals upskill? This is not only a matter for undergraduate education but for graduate education – to increase depth, breadth and capacity. Our undergraduate programs already struggle to survive in a market-based university sector exactly when we need them to be strong. Beyond them, at graduate level, what specializations can we take from other programs for our own benefit and what, in turn, can we offer them? How will the higher degree students and the research we need for our future as a profession be funded?

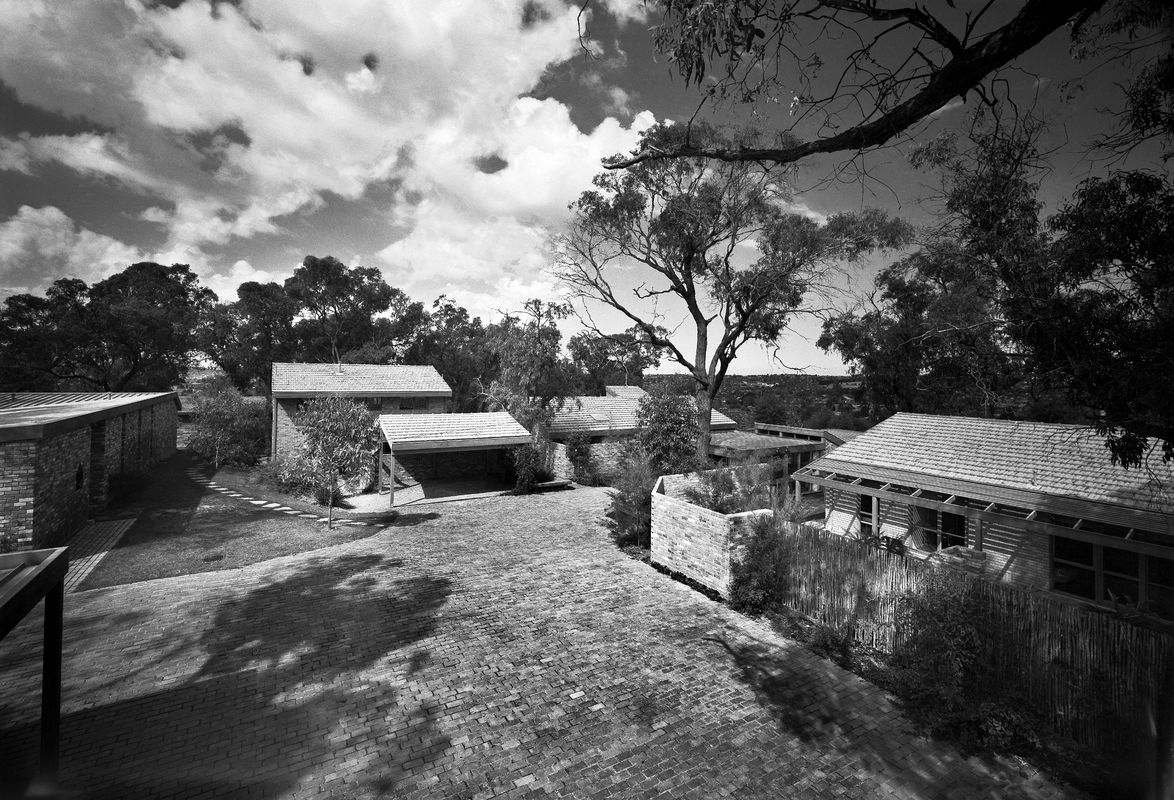

Vermont Park, a 1977 cluster housing project in Melbourne by Merchant Builders and Tract Consultants, offered a new model for Australian housing.

Image: John Gollings.

All this goes to what constitutes a profession. Beyond individual capacity, a profession commands a discrete body of knowledge. It acts in a “field of operations;” it must be able to “profess” or articulate what its knowledge is and how its particular application of that knowledge contributes (as “know-how”). It must have credible centres from which to argue its case and credible arguments that are visible where decisions are made.

While such questions may appear to be far from current concerns, especially for practitioners concerned about the source of their next project and academics concerned about their jobs, I argue that these questions go to the heart of the profession’s survival and development in the coming decades. Now is precisely the time for our early- and mid-career graduates to consider higher degrees to expand the breadth and depth of their skills. Now is precisely the time to expand our research and research training to provide the profession’s evidence base. Now is precisely the time to use the projects that will come our way, and the hard-won funds that result, as investments in our future. The next five years are an opportunity for the profession to reorient and step up to the next level. Not only should it produce great projects, it should invest public, professional and personal funds toward the research and education that ensures the coming generations of landscape architects are well prepared and equipped to make the profession’s contribution central to national development.

Source

Practice

Published online: 16 Aug 2020

Words:

Catherin Bull

Images:

John Gollings.,

John Oldham.,

Peter Bennetts,

Roads and Maritime Services.,

State Library of Western Australia, 011386D

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2020