Until the end of the 1980s, nearly all suburban houses in Australia had large backyards. Today, these older suburbs commonly have backyards of at least 150m2. They are often several times as big, and usually have significant tree cover. On these older lots, also often known as blocks, houses generally cover 20–30% of the area, with a maximum of 35–40%.

In the early 1990s, this began to change dramatically. The provision of large backyards in new constructions ceased, and the figure of 35–40% lot cover is now a minimum rather than maximum. Although there are backyards of 100 m2, most are much smaller — often less than 50 m2. Moreover, the gap between the dwelling and the lot’s side and rear boundaries is frequently a thin strip of land rather than a more useful square.

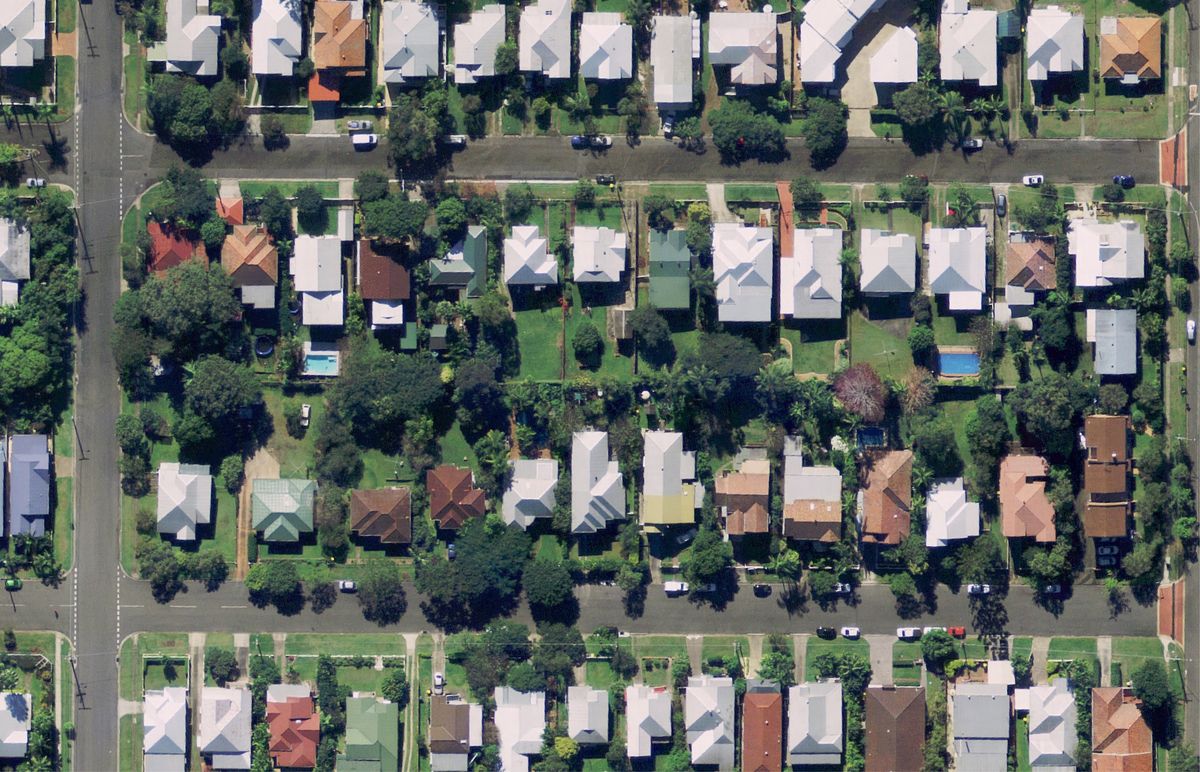

This change has not been subtle or gradual. It is immediately apparent from even a cursory examination of aerial photographs that there are two distinct patterns — older areas have tree cover, while in the newer ones dwellings can be nearly roof-to-roof.

Aerial view showing a housing scheme at Carina, Brisbane, built in 2007–08. Note the older suburban layout with large backyards on the lefthand side of the main road.

Image: AUSIMAGE© Sinclair Knight

Is this the result of smaller suburban lots? There is a trend to smaller lot size in Australia, but it is the increase in the dwelling area, rather than the decrease in the lot size, that has led to shrinking suburban gardens. There has been a trend towards deep, square houses with large internal spaces, little natural light and ventilation, and fewer and smaller windows. Narrow gaps around the houses are often lined by high opaque fences. The frontage is dominated by integral garages. You can find all of this everywhere in Australia, including outback towns, and it can be at its worst in the outer suburbs of cities where lots are still fairly large.

What are the effects of bigger dwellings?

Why should the minimisation of green space around buildings be a problem? Domestic backyards and communal green space for apartments have an ecological function and importance that goes beyond the interests of the individual household. In newer residential developments, only a small proportion of the total land area is permeable and planted, aside from the front lawns. There is now no room for trees at the sides and backs of the houses, which means a substantial and lasting reduction in suburban tree cover. Although there may be space for shade trees at the front, they are rarely provided.

The interaction of trees, plants and water is important in helping to make a more pleasant microclimate, especially in hot and dry Australia. The reduction in width between dwellings makes natural ventilation very difficult. The narrowness of the gaps between the houses prevents airflow around them, creating heat-island effects. Prevailing winds skim over the roofs without exerting enough air pressure within the gaps to create natural ventilation. The problem is exacerbated by exhaust from air-conditioners and by the use of dark-coloured roofs which absorb, rather than reflect, the heat. All this results in an unpleasant milieu around the house and increased electricity consumption for the residents.

The reduction in permeable surface areas increases stormwater run-off, which means increased costs for concrete stormwater drains, not just within any development but also for other communities ‘downstream’. It also means a loss of water that could have been used on site for local plantings, which would encourage biodiversity. This is particularly important in the Australian climate, where long dry spells can be punctuated by episodes of heavy rainfall.

A street scene in Spearwood, Perth, Western Australia. Note the extensive paved areas, few windows and dominance of wide garages.

Image: Tony Hall

What we are losing

In the older suburbs, garden plantings (‘soft landscaping’) in adjoining backyards host a high degree of biodiversity. Domestic gardens have a density and variety of plantings that is not found elsewhere. When we minimise or eliminate planted areas, there are serious consequences for biodiversity in general. Another major advantage of the extensive plantings on older suburban lots is that they can absorb or ‘sequester’ carbon dioxide and various other pollutants from the atmosphere. Reducing the area of planted green space within a residential development reduces carbon sequestration just when and where it is most needed.

In addition to these benefits to the community as a whole, backyards provide important benefits to individual households. The most important ones — relating to outlook and natural ventilation — apply even if the occupants never venture out into their backyards. One of the most important roles of private open space around the home is to provide a pleasant outlook from inside the dwelling. Where the backyard has been reduced in size or even eliminated altogether, the degree of enjoyment of the house by its occupants also diminishes. Spaces around new outer-suburban houses now are rarely big enough for an in-ground swimming pool. Barbecues may be possible, but space is limited and there might be less opportunity for large outdoor social gatherings. There is not enough space and sunlight to grow fruit or vegetables, and large external rainwater tanks and home composters might also be ruled out. The ability to dry laundry in the open air becomes limited. Children are the principal sufferers. There is little outdoor space for them to run around in and make a noise without disturbing others, while they are in a secure environment with a responsible adult keeping watch from inside the house. This is especially important for very young children.

Why do we choose to live in such houses?

Data suggests that the reduction in backyard size in Australia has coincided exactly with substantially longer working hours for middle and higher income office workers. At the same time, the growth in the use of air-conditioning has not only allowed but encouraged an indoor lifestyle. For people buying a suburban house, the focus has become one of investment in buildings, resulting in houses that maximise floor area for minimum construction cost. Planted space around the house is not seen as an investment, and dwellings therefore extend over as much of the lot as is permitted.

Planning policies

Planning codes in different parts of Australia commonly stipulate that at most about half of a suburban lot can be covered by the dwelling. This might seem reasonable at first sight, but a 2 metre gap around the edge of the lot can easily occupy nearly half of the total area. Some codes require the provision of an outdoor area open to the sky, next to the main living area, but the minimum area is always very small, commonly 16m2.

Although the sizes specified may be inadequate, many building codes do refer to the need for space around houses in terms of amenity value for the occupants. Consideration of the environmental role of the space is almost wholly absent. Moreover, there are no positive policies that ensure the provision of tree cover either at the front or the back of the lot, or through providing shade-giving street trees. In short, the codes do nothing to prevent the loss of significant backyards, nor do they promote the environmental benefits of vegetation around houses.

Green space around dwellings has important social and environmental functions and is an essential component of sustainable living. We cannot simple substitute public parks — we need to improve our thinking about how we integrate planted areas within the urban fabric. The demise of individual suburban gardens should concern all Australians.

This article was originally published in Australian Garden History, volume 27 no 2, October 2015.

For the full story see Tony Hall’s “The life and death of the Australian backyard”, CSIRO Publishing, 2010, winner of the 2012 Planning Institute of Australia Award for Excellence in Cutting Edge Research.