In 2019, the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects declared a climate and biodiversity emergency – but what does “and biodiversity” mean, and how do we accommodate it?

In 2020, 50 of the world’s leading experts from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services met for the first time to understand the synergies and trade-offs in planning for climate change and biodiversity loss separately. They found that “Biodiversity loss and climate change are inseparable threats to humanity that must be addressed together”1. Indeed, corporations in Australia are soon to feel the impact of this statement with biodiversity loss risk reporting anticipated to join existing climate change risk disclosure requirements in 2023. This means corporations will need to investigate, mitigate, and report on biodiversity impacts in their business, alongside climate risks. Corporations will need to practically determine how to assess their operations for both, forcing these two areas to be integrated in practice. This will have flow on effects for the landscape architecture profession in terms of how we act, meet client needs and community expectations. This change could bring considerable benefits for the sector as more clients actively seek biodiversity gains. To take a leadership position in this conversation, we, as landscape architects, must consider how to practically integrate our responses.

How do the concepts of climate change and biodiversity align?

The overall goal for biodiversity is net gain across a project or organization. Biodiversity approaches focus on reducing the ecological impacts of activities through strategies that “avoid, minimise, regenerate, and offset” biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation.

The overall goal for climate change is a climate-positive organization or design. Mitigation and adaptation strategies seek to reduce scope one, two or three greenhouse gas emissions, use of embodied carbon-intensive products, and the “felt” impacts of a changing climate, such as urban heat. Scope 1 emissions (as per the Greenhouse Gas Protocol) are direct emissions from owned or controlled sources, for example, car usage; Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from purchased energy, for instance, heating buildings; and Scope 3 emissions encompass all other indirect emissions in a company value chain.

The complexity comes from the fact that these concepts must be integrated at a range of organizational levels and scales by navigating a plethora of approaches and tools.

Delivering a design that integrates climate and biodiversity considerations at different scales is a complex matter. (Photo: grey-headed flying fox)

Image: Andrew Mercer, CC BY-SA 4.0

Tackling the change at different levels and scales

To enable an integrated response throughout an organization the role of different levels and scales must be considered.

At the strategy level, boards and senior management must define the organization’s response, from a joint climate and biodiversity declaration to an integrated climate and biodiversity strategy. This needs to be informed by experts and backed up by resources to assess the value chain footprint for both climate and biodiversity, set evidence-based targets and cascade commitments through business plans to policy and operations. This may mean asking hard questions about what activities will be accepted under what conditions, including projects that have impacts in one domain but not the other.

To be effective, an organizational mandate must be embedded in daily operational workflow, with measurement and reporting to ensure tactics are delivering the anticipated results. Project-level considerations extend from inception to maintenance. Scenario planning around the impact of a changing climate and what novel ecosystems mean for future scenarios become key. For instance, will our selection of plants be climate resilient? Will our choice of materials reduce heat? How can our designs reduce the impact of higher and more frequent flooding? What invasive species may arrive? How do we determine how the built environment will need to perform over its lifetime, including what species and structures will maximize biodiversity, but also be resilient to a changing climate? The principles of connection to and care for Country should underpin all decisions2.

The project level is also where questions of scale come into play. How can we deliver a design that integrates climate and biodiversity considerations in hyper-local projects in streets and parks, through to regional-scale planning? This diversity of scales presents some head-scratching moments, as what matters for people and biodiversity at each scale can change. This is further complicated when we consider the needs of different species or people. For example, for select invertebrate pollinators local context in patches matters most, but for the grey-headed flying fox, a landscape-scale response is key3.

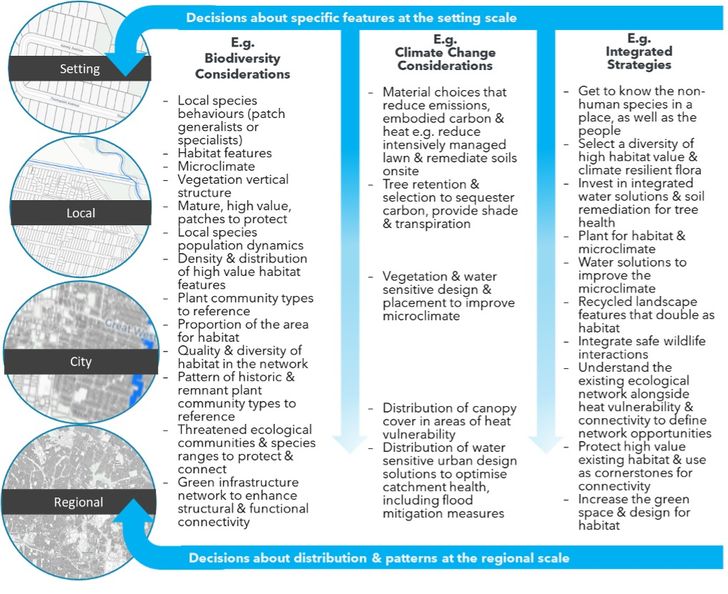

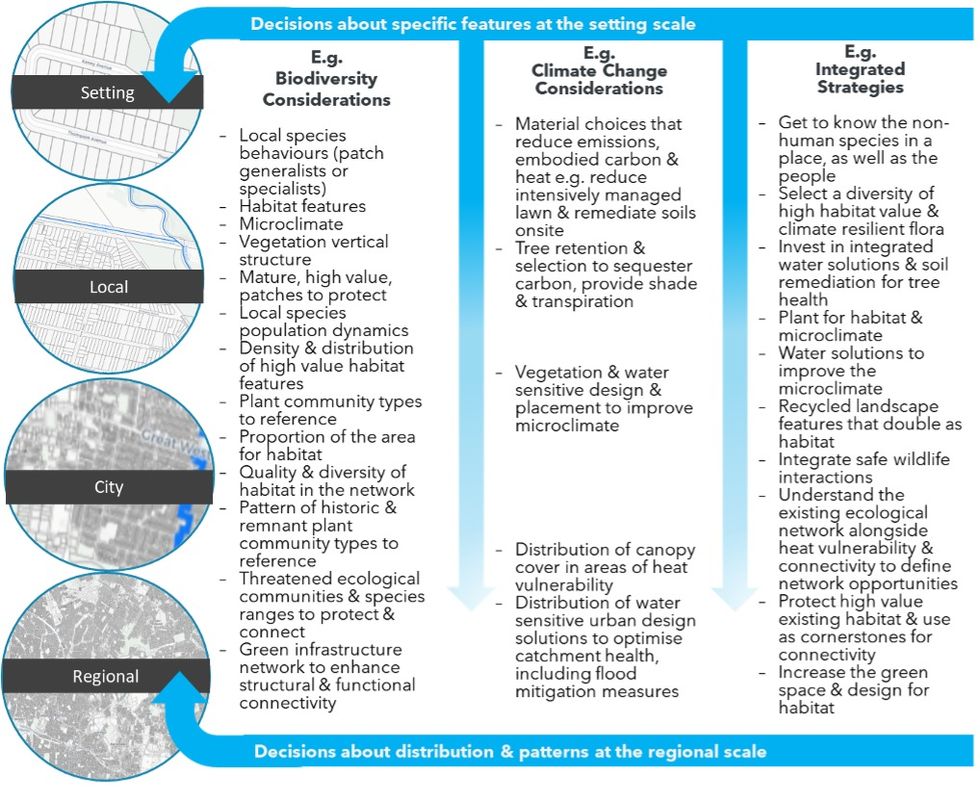

One way to navigate these issues is to take a “nested” approach4. At the centre are settings, such as streets or residential gardens. These are nested in neighborhoods, then cities and finally regions. How deeply one delves into each scale depends on the project’s objectives. For example, all projects will benefit from understanding the network of green spaces that surround a site, in particular the location of quality remnant patches with high biodiversity that can act as feeder sites into the local ecological network, how connected they are, the plant community types and species they support. For local projects, questions of how to enhance, replicate, and connect critical habitat features for select species becomes key, such as via plant choice and placement or habitat analogues. Once these dimensions are understood, attention can be directed towards making the space “safe” from a changing climate, for example using materials with low embodied carbon, permeable and heat-reflective surfaces and providing continuous canopy cover. At the city scale, GIS-based tools provide an avenue to test different scenarios on sites, such as how functional connectivity can be improved for different fauna or invertebrate groups, alongside climate adaptation strategies for residents. At the end of the spectrum sit regional-scale projects that require a landscape conservation approach. In these projects GIS becomes key, to map biodiversity values and understand where strategic interventions can occur for habitat connectivity, protection, and improvement, as well as climate adaptation and mitigation.

Nested scales approach to integrating climate and biodiversity considerations in projects

Image: Georgina de Beaujeu and Julie Lee

Looking for the win-wins in every action

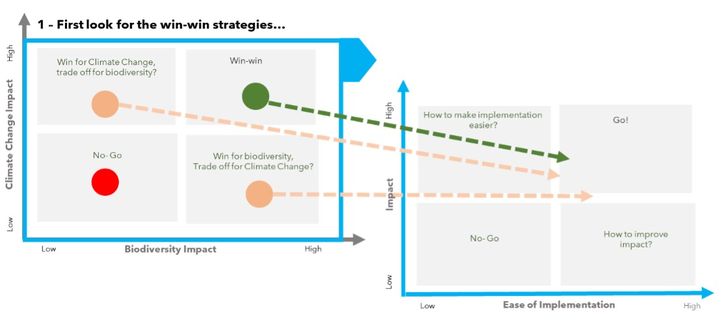

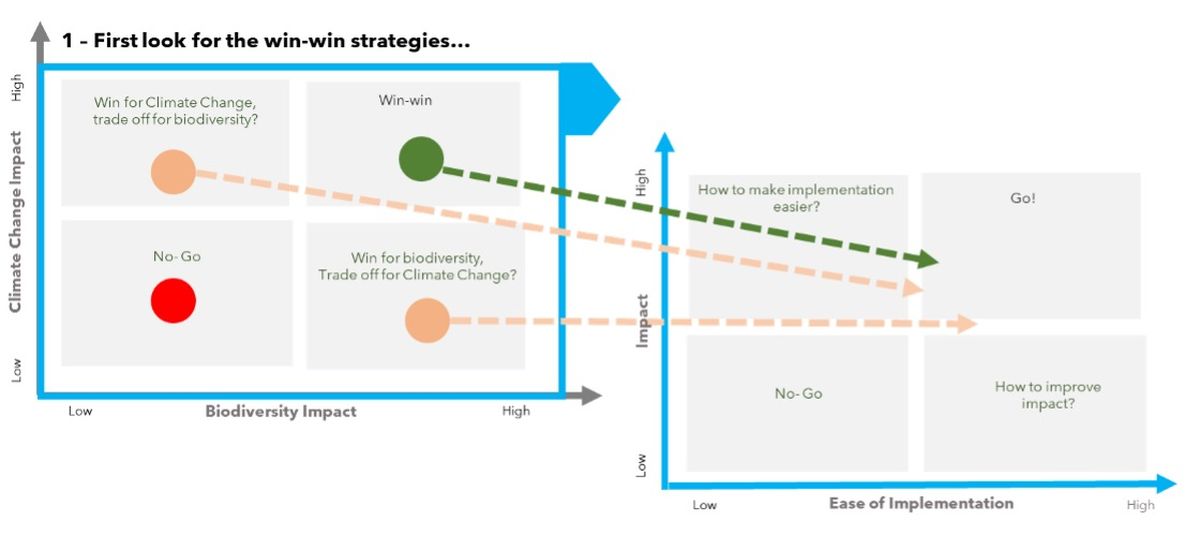

Irrespective of where one starts, as designers we are looking for win-wins, for example where species are selected for climate resilience and biodiversity benefits, where additional connectivity can reduce road surface heat. Creating win-wins draws us back to the idea of nested scales as it requires us to understand the conservation matrix at different scales – like we do the suburban matrix for people – and bring these views together with climate scenarios as we make planning decisions in our cities and neighborhoods. This means understanding the existing ecological network and considering how we maximize the quality and diversity of patches, corridors, and steppingstones to deliver the most benefit for the most species, and then overlaying climate scenarios to see where there is alignment and where trade-offs are required.

One simple tool entails mapping proposed strategies on a matrix to determine which will deliver a win-win and then considering the ease of implementation (and cost) of options to assess which trade-offs are most palatable.

Searching for win-win biodiversity and climate change strategies

Image: Georgina de Beaujeu and Julie Lee

Where to from here?

As yet, there is no golden tool that will integrate both concepts at every level and scale, but rather a path that needs to be committed to with a sense of urgency. This path involves assembling a practice’s best and equipping them with the knowledge and resources to determine which decisions hold the greatest potential for win-wins. Landscape architecture as a profession must take a leadership role in showing how this can be done.

1. Collins, T, (2021) Media Release; Tackling Biodiversity & Climate Crises Together and Their Combined Social Impacts, Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) https://ipbes.net/sites/default/files/2021-06/20210606%20Media%20Release%20EMBARGO%203pm%20CEST%2010%20June.pdf

2. Mata L, Ramalho CE, Kennedy J, Parris KM, Valentine L, Miller M, Bekessy S, Hurley S and Cumpston Z (2020) Bringing nature back into cities, People and Nature, 2(2):350-368, https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10088

3. Kirk H, Threlfall C, Soanes K, Ramalho C, Parris K, Amati M, Bekessy S and Mata L (2018) Linking Nature in the City: A framework for improving ecological connectivity across the City of Melbourne, The Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub, https://nespurban.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Kirk_Ramalho_et_al_Linking_nature_in_the_city_03Jul18_lowres.pdf

4. Goddard M, Dougill A, Benton T (2010) Scaling up from gardens: biodiversity conservation in urban environments, Trends in ecology & evolution, 25(2):90-98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.07.016