Which projects represent the foundations of the landscape architecture profession in Australia? AILA was born from a diverse array of professions. Its early members included architects and planners, horticulturalists and garden designers, and grassroots environmentalists and artists, all unified in the belief that the designed landscape had value and meaning worthy of recognition, protection and a creative response. In generating a shortlist of over thirty projects we, the jury, tried to capture projects that reflect the maturation of the Australian profession, one that is now recognized internationally. Our search stretched back to the 1960s in order to find ten outstanding contributions recognized by practitioners and the public alike. We were looking for projects that have stood the test of time, maturing into landscapes of distinctive character and appeal. Other considerations included national reach and an expression of the dynamic qualities of landscape and the subtle ways landscape sustains daily living. We found these qualities in projects of infrastructure, residential subdivisions, parks, gardens, institutions and the urban fabric of the city itself. Some of Australia’s notable landscapes – such as Parliament House in Canberra, Millennium Parklands in Sydney, and projects from arid inland Australia such as Yulara sparked acute debate. The response triggered by such projects represents the difficult years establishing the profession, when its identity was tested but a wave of practitioners was propelled into the new millennium.

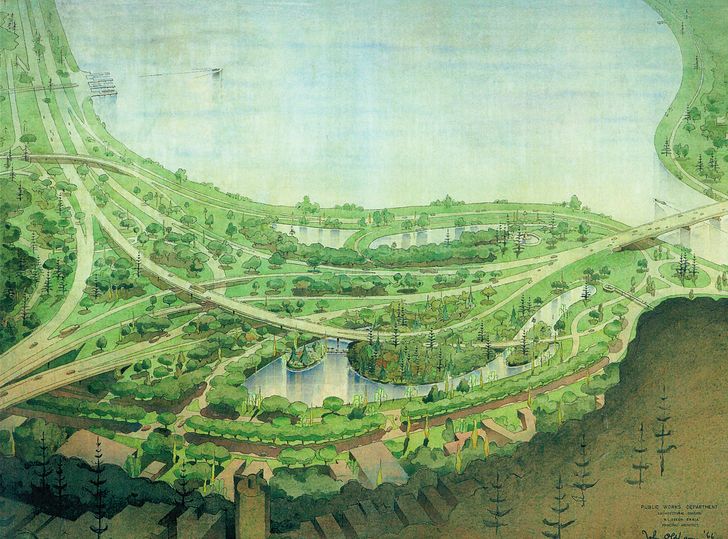

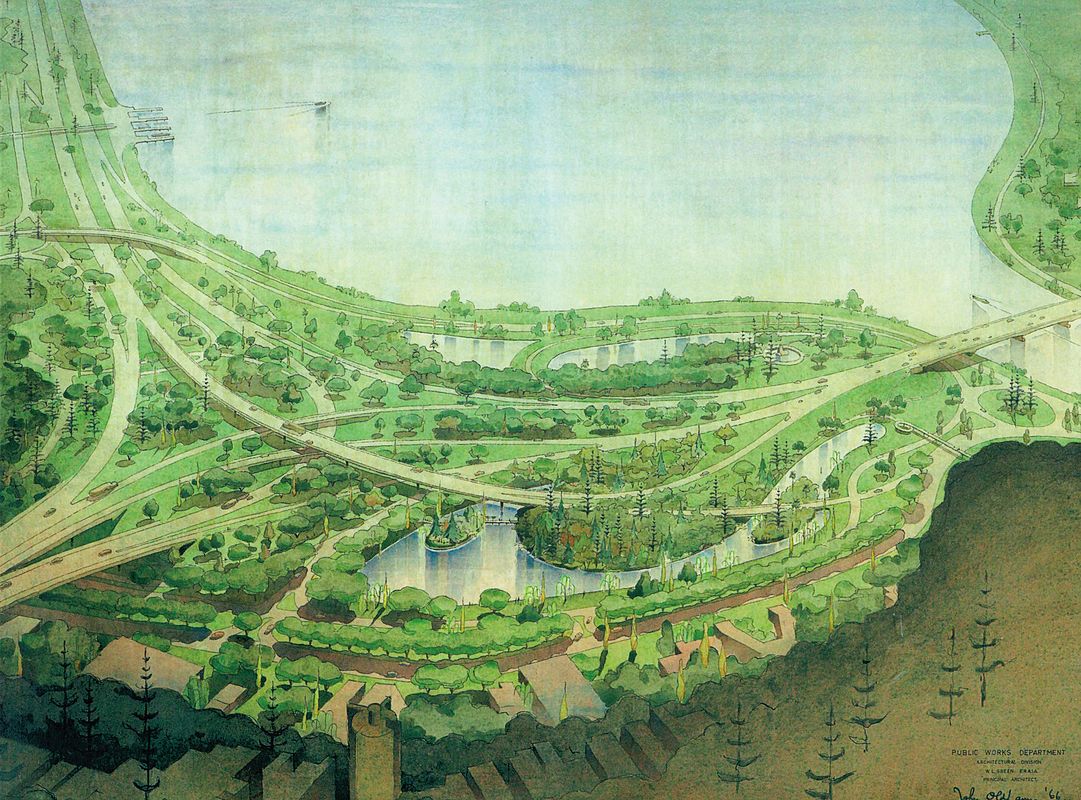

Infrastructure projects provided a foothold for the profession in its nascent years. Such work helped define new forms of landscape design that was distinct from the design of the domestic garden. The acceptance within bureaucracies that the design of freeways dams, power stations and the like required more considered thought, was an achievement for practitioners and is still relevant today. Professor Peter Spooner paved the way for collaboration between landscape architects and engineers through his design work on the Sydney to Newcastle Expressway (1967). Engineering decisions were profoundly influenced and thus expressed a new appreciation of the relationship between designed infrastructure and the natural landscape, heightening the experience of road travel. The Narrows Interchange in Perth, a project that required the filling-in of a greatly valued part of the Swan River, gave architect John Oldham the opportunity to sell to the public the advantages of creating a major public park beneath and around a freeway interchange. His actions simultaneously launched the landscape architecture profession in Western Australia.

These commissions were of their time – their designe rs accepted the inevitability of infrastructure and attempted better outcomes for the profession amidst opportunism. In parallel, the recovery of despoiled sites and ruined landscapes was of equal significance. The contribution of Bruce Mackenzie and Associates on the post-industrial foreshores of Sydney Harbour formed another crucial front for advancing the profession’s relevance. Illoura Reserve at Peacock Point and Yurulbin Park at Long Nose Point, both in Balmain, represent some of the earliest attempts to reclaim the visual qualities of a lost indigenous landscape. Beyond these two projects, the oeuvre of Mackenzie’s contribution is vast and the technological advances made in contemporaneous work (such as at Sir Joseph Banks Park Botany Bay and the William Balmain Teachers’ College, Lindfield, later the University of Technology, Sydney’s Kuring-Gai campus) broadened practice for landscape architects across Australia. Of concern to Mackenzie was how to establish new ways of living with the Australian indigenous landscape. He applied new techniques across different projects, from residential to institutional to larger scale open space systems.

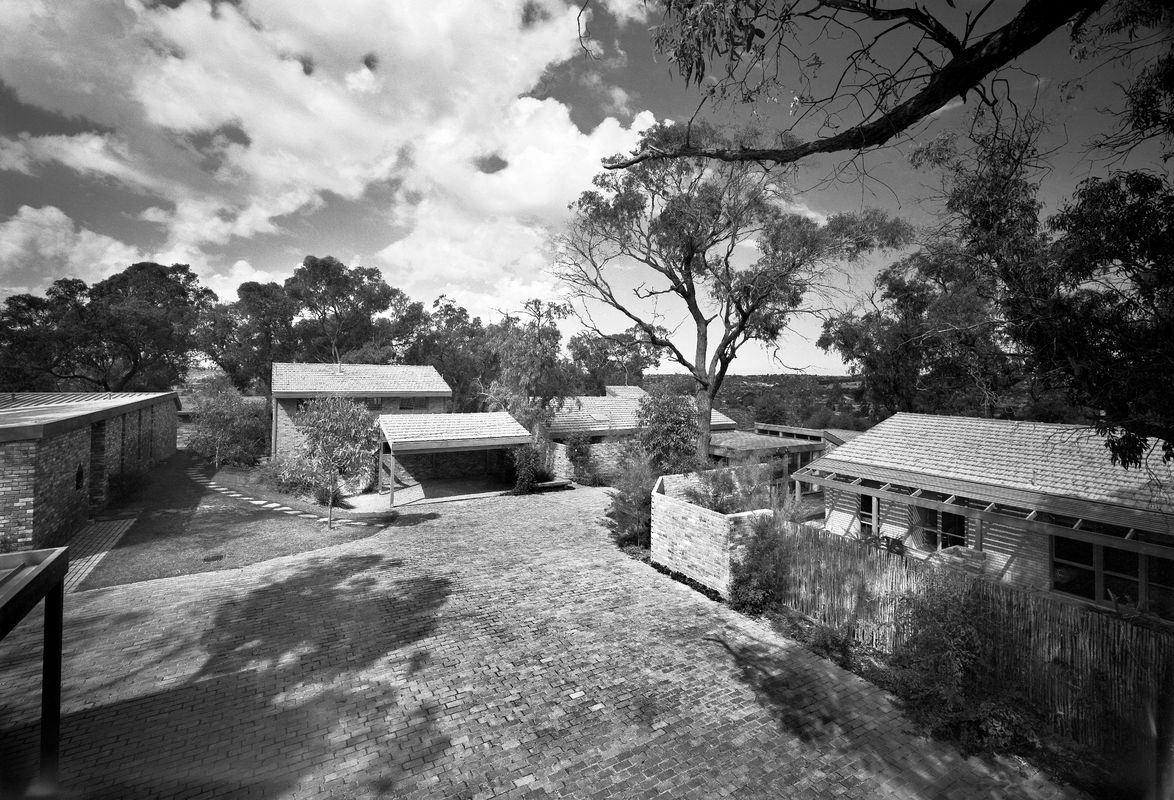

The contributions of the project-house building firm Merchant Builders are important because of their innovation and leadership. The Winter Park, Elliston and Vermont Park projects tested new ideas for subdivision design in Victoria and were correspondingly advanced in New South Wales by Pettit and Sevitt (and architect Michael Dysart). Perhaps fortuitously, Merchant Builders also synthesized the older world of landscape design with the newer profession of landscape architecture through their associations with landscape architect Ellis Stones and firm Tract Consultants who each made crucial contributions in their own right.

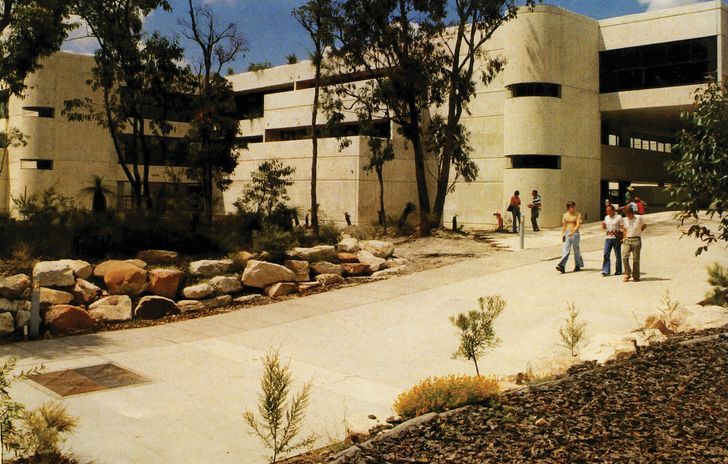

Contrasting in scale and type, two projects stand out as exemplary in responding to pre-existing landscape values. At an institutional level, the campus and landscape of Griffith University’s Nathan Campus, Queensland deserves recognition for locating a new institution within a pre-existing landscape frame. Griffith persists today as a functioning university, and despite new developments since the 1970s, the campus environment still exhibits many of the qualities initially projected. At a larger scale, approximately thirty-six kilometres and five-hundred hectares of the River Torrens in South Australia became the subject of a major planning and design investigation by Hassell and Land Systems, a project that as well as being firmly collaborative, was based on ecological planning and an integrated approach within the urban fabric of Adelaide.

It was also crucial to find a role for landscape architecture in retrofitting urbanized sites. The designed landscape as a garden and a semi-public space able to hold a specific functional requirement and express a clear aesthetic vision found traction in the South Lawn at the University of Melbourne and the Sculpture Garden at the National Gallery of Australia. These projects have their own unique design qualities, each far too complex to elaborate on here, but the significant aspect both share is how the designed landscape has a binding effect on urban space, unifying architecture and garden and city in a continuum. The idea that a garden of great complexity and distinctiveness could coexist with a city’s character and fabric elevated the need for landscape design in the urban context to a new level.

The motivation to transform Australian cities continued into the 1980s. Change has been the result of a combined effort of multiple individuals, organizations, governments and professions attempting to claim a slice of “urban design.” Two contrasting projects have succeeded in different ways. South Bank in Brisbane is a hallmark transformation of a post-industrial waterfront and a transformation relevant to every major city in Australia. If South Bank initiated comprehensive and large-scale change, the gradual and incremental transformation of the Melbourne CBD serves as a striking contrast. In the mid-1980s, initiatives from the then Ministry of Planning and Environment and the Melbourne City Council’s Department of Urban Design and Architecture, included the humble makeover of Hardware Lane and McKillop Street. In 1986 the Ministry received an AILA Award of Merit for a stunt that saw Swanston Street, the city’s major vehicular spine, almost completely turfed for two days in February 1985 as part of Victoria’s sesquicentennial celebrations. As an early form of landscape (art) installation, the roadway, tram stops, kerbs and bitumen were swamped in green and Melburnians awoke to a different version of their city.

Similar projects followed: Postcode 3000, a program that ran between 1992–2000 and was designed to bring residential living back into the city; increased pedestrianization and the eventual creation of Swanston Street Walk; and the redevelopment of the banks of the Yarra River, including Federation Square, which came many years after the ministry’s initial proposals in the 1980s. Innumerable forces have emerged, including street artists, shop owners, buskers and myriad other expressions of “street life,” adding to the experience of the city. Pinpointing the authors of change is an impossible task in some ways. And not all change has brought favourable or instantaneous results. But as our cities evolve, and complex social and environmental issues emerge, landscape architecture must remain a vital part of the dialogue.

Sydney to Newcastle Expressway by Peter Spooner, New South Wales Department of Main Roads, 1962–1967.

Image: Courtesy Roads and Maritime Services

The Narrows Interchange Parklands (Perth) by John Oldham, Public Works Department (Western Australia), 1963–1974.

Image: John Oldham

Sydney Harbour Parks: Illoura Reserve and Yurulbin Park by Bruce Mackenzie and Associates, 1970–1974. Pictured here is Yurulbin Park.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Residential Subdivisions by Merchant Builders by Ellis Stones (Winter Park and Elliston), Tract Consultants (Vermont Park, 1970–1978. Pictured here is Vermont Park, Victoria.

Image: John Gollings

The South Lawn, University of Melbourne by Ronald Rayment and Ellis Stones with Loader and Bayley in association with Harris, Lange and Partners, 1971–1973.

Image: Courtesy University of Melbourne

Griffith University landscapes by University Buildings Division: Roger Johnson (1972), Alan Cole (1973), Neil Thyer (1973) and Sam Ragusa (1978).

Image: Courtesy Griffith University

River Torrens Study by Hassell and Partners and Land Systems (now Hassell), 1979.

Image: Courtesy Hassell

National Gallery of Australia Sculpture Garden by Harry Howard and Associates and Barbara Buchanan with Edwards, Madigan, Torzitlo and Briggs, 1982.

Image: Dianna Snape

South Bank Parklands (Brisbane) by Gillespies Australia with Denton Corker Marshall, 1997–1999.

Image: John Gollings

Central Melbourne: Framework for the Future by City of Melbourne – Hardware Lane, McKillop Street and Swanston Street, Victoria,1985–ongoing. Pictured here is the Swanston Street Party (1985).

Image: John Gollings

———

Andrew Saniga is a senior lecturer in landscape architecture, planning and urbanism at the University of Melbourne. His book, Making Landscape Architecture in Australia (2012) has won two AILA awards. He is currently lead chief investigator for an Australia Research Council Discovery Project grant for a three-year project titled Campus: Building Modern Australian Universities.

Elizabeth Mossop is a founding principal of Spackman Mossop and Michaels, a practice based in Sydney and New Orleans. She is the dean of Design, Architecture and Building at the University of Technology Sydney and has held leadership positions at Harvard Graduate School of Design, the LSU Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture and University of New South Wales.

Dawn Casey has held the position of director at the Western Australian Museum, Powerhouse Museum in Sydney and National Museum of Australia in Canberra. She was responsible for managing the design and construction of the National Museum of Australia and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies through a world first project delivery alliance contract.

Source

Review

Published online: 22 Feb 2017

Words:

Andrew Saniga

Images:

Courtesy Griffith University,

Courtesy Hassell,

Courtesy Roads and Maritime Services,

Courtesy University of Melbourne,

Dianna Snape,

John Gollings,

John Oldham,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, November 2016