Garden design? Landscape design? Perhaps even both? Such questions are posed by the design of Medhurst, a contemporary rural estate that looks across the Yarra Valley to the distant Yarra Ranges National Park, surely one of Victoria’s most sublime and picturesque landscapes. Apart from the walled picking garden that is so carefully distanced from the house and its immediate surrounds, the estate is not really considered as a garden, even by the owners. Their “garden,” after all, requires so little real “gardening” or cultivation in the traditional sense. To them, to the landscape architects at Tract Consultants, to the architects at Denton Corker Marshall (DCM) and to anyone who visits, this house both inside and out is all about its broader landscape setting. Perhaps the whole valley is Medhurst’s garden.

As a contemporary expression of modernist landscape design – something unusual in Australia, especially in the rural environment – Medhurst might even be considered a provocation. Here Steve Calhoun and Helen Wellman from Tract Consultants eschew the traditional design devices of spatial and material complexity, and typical planting, to create an immersive garden experience. These are, it seems, even avoided and their design devices are instead essentially tectonic and sculptural. Mass, volume, space and sequence are artfully employed to create a variety of settings immediate to the house. The house, the “garden,” the landscape – and all the elements that make these – combine to complement each other in a seamless sculptural composition. As with the best modernist work, such apparent simplicity disguises the design achievement and mastery of form and space.

While the idea of simple sculptural perfection may seem remote from the messy realities of domestic life, the Medhurst home environment is far from sterile. As testament to the skill of its designers, domestic life here is enlivened and enriched by the way the house and its immediate landscape provide multiple platforms from which to experience at close quarters the day-by-day rhythms of the landscape around and beyond.

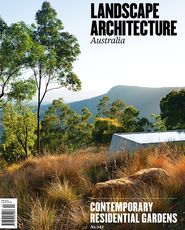

From the road and gate, the house is seen as a commanding presence on the hill crest above the dam.

Image: Dianna Snape

To understand how this occurs and how the surrounding landscape becomes, for want of a better word, the “garden” of Medhurst, it is necessary to explore how that landscape is modified and humanized to provide places of comfortable habitation that link it to the central sculptural piece, DCM’s building.

Set on a crest at the valley’s edge, the house comprises a pair of rectangular prisms, each just a single room wide. These prisms are stacked longways so that the upper prism cantilevers five metres beyond the lower, which recedes into its embracing sculpted grass slope. The upper prism accommodates the living and entertainment spaces as well as the main bedroom, which cantilevers to command a prime view of the valley. The lower prism accommodates the bedrooms, entry and cellar. As with any sculpture, great care has been taken to place it to maximum effect in its setting. The driveway, which leads from the nearby road along the valley floor, is designed using traditional picturesque techniques. From the road and gate, the house is seen from below as a commanding presence on the hill crest above the dam and grassed slope. The drive then sweeps away from that view past the Medhurst winery (a dramatic architectural and landscape composition in itself) as a track through the surrounding eucalyptus woodland, to arrive at the grassed clearing within which the house (or sculpture) sits. Seen here at their most sculptural, the series of prisms and their platforms emerge from the surrounding manicured landscape, their uncluttered simplicity backlit by the sky in dramatic contrast with the ragged verticality of the nearby eucalyptus grove.

Looking back upon the house from the pool area, the hard planes of concrete are softened by overhanging grasses.

Image: Dianna Snape

In a final flourish, again the drive sweeps away, only to arrive at the point where the cantilever frames and introduces a dramatic view of the Yarra Valley and ranges beyond. Here the approach journey changes from the vehicular to take the pedestrian either through the front door and up a lateral slope of steps, or via a choreographed sequence of walled external corridors, stairs and external terraces (or rooms), to the living areas above. A paved pool “room,” a turfed living “room” – each furnished in the simplest of styles. The sparest palette of materials is used – massive blade walls and pavements of concrete and stone, minimal glass balustrades, turfed slopes. The pool operates as a reflective plane mirroring the sky. Grasses and a single Bosc pear tree are the few geometric planted masses that complement the composition. The play with mass and transparency extends from the house into these spaces and while nothing clutters or competes with the view of the broader landscape, the transition in spatial scale creates accessible places around the house and invites use. These spaces and the landscape beyond comprise the house’s “garden.” To reduce the potential for distracting foreground clutter, the one truly cultivated area of vegetables and picking plants is contained within its own rock-walled prism and carefully sited “off-vista” to the side and rear.

A cultivated area of vegetables and picking plants is contained within its own rock-walled prism and carefully sited “off-vista” to the side and rear of the house.

Image: Dianna Snape

Internally, the layout creates a series of single, sparely furnished rooms strung out along the crest in the simplest of sequences – service, kitchen, dining, living, entry, main bedroom. Externally the layout is similarly simple and spare, a mannered composition, responsive to the particularities of the architectural concept and the site. It is, nevertheless, by virtue of its command of spatial scale and form, both used and usable.

As a designed landscape this “garden” provides a robust but subtle transition between its strong, some would say overwhelming, broader landscape setting and its equally strong, and again some would say overwhelming, house – a house conceived as a sculpture for living. In terms of garden design traditions, the Medhurst garden per se hardly seems to be there, but it is there, and brilliantly so. If one accepts John Dixon Hunt’s proposition that as a third nature,

a garden is a place whose purpose is, in essence, to experience nature, then undoubtedly and uncompromisingly the landscape of Medhurst is a garden. The surrounding landscape – the Yarra Valley, the ranges, the vineyards, the forest – is not just borrowed, as with a typical picturesque design. It is integral and even, it would seem, the garden’s very purpose.

Credits

- Project

- Medhurst

- Practice

- Tract Consultants

Australia

- Project Team

- Steve Calhoun, Melissa Dunlop, Helen Wellman

- Consultants

-

Architect

Denton Corker Marshall

Irrigation design and construction Planned Irrigation Projects

Landscape contractor PTA landscapes

- Site Details

-

Site type

Rural

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 6 months

Construction 3 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens

Source

Review

Published online: 3 May 2016

Words:

Catherin Bull

Images:

Dianna Snape

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2014