In contemporary society play is often seen as the exclusive domain of children, or at best a sign of immaturity or frivolity in adults. For example, when we refer to “child’s play,” we refer to something that is easy or simple, while “just playing around” implies a lack of seriousness or direction. In contrast, Huizinga’s observation reveals the complexity of play as “an act apart” that involves the temporary suspension of ordinary life for an imaginary life – one in which ideas and activities are developed, tested and performed within a safe environment. In 1974, environmental psychologists Hayward, Rothenburg and Beasley noted that:

“… the opportunity to play enhances one’s ability to initiate independent activity – activity which is crucial to the exploration and construction of one’s autonomy, identity and self-image as a constructive force.” 2

When seen from this perspective, play is an essential part of the formation of identity: a process that is common to both children and adults throughout their lives. In fact, playspace designers may exert considerable influence on the development of society, so our task is complex and deserves careful consideration.

Playgrounds are particularly interesting places as they reflect changing philosophies concerning the role of play and the place of children within Australian society. For example, if we contrast the brightly coloured adventure play sets that occupy many contemporary playgrounds today with the functional “four Ss” (swing, sandbox, slide and seesaw) popular in the postwar era, we might conclude that society has become more attuned to the needs and wants of children over the past fifty years. Yet many play theorists are still expressing concerns about the decline of unstructured and outdoors play while drawing links to the rise in childhood health concerns such as obesity, depression and attention deficit disorder.

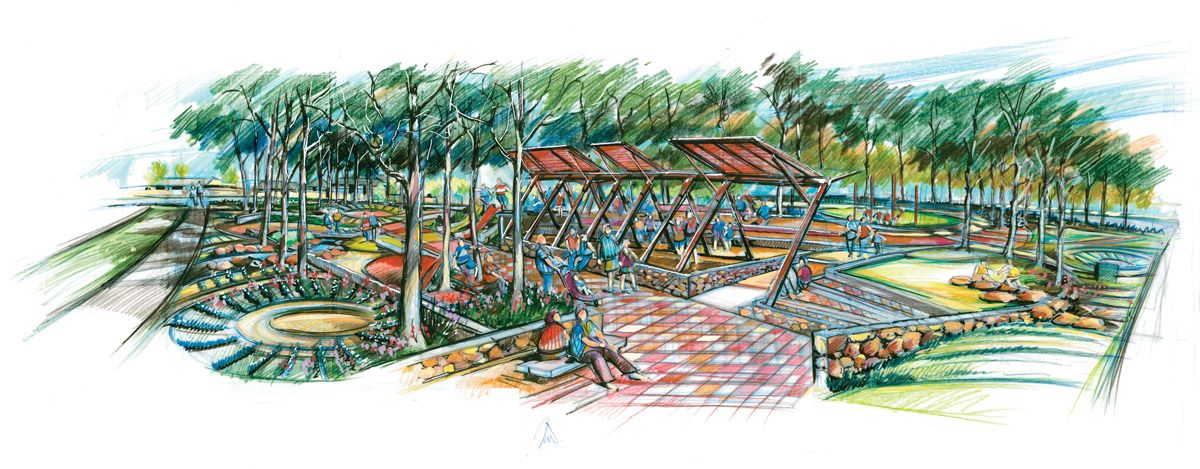

CPG Australia’s Rooke Reserve in Victoria.

Image: courtesy of CPG Australia.

The reasons for this decline in outdoors play are complex and varied and range from concerns for child safety (“stranger danger” and bullying), the densification of urban neighbourhoods and a general lack of open space where new play areas might be built. In a recent CSIRO publication, The Life and Death of the Australian Backyard , Professor Tony Hall notes that the recent popularity of the manicured landscapes popularized in TV shows like Backyard Blitz has resulted in the decline of the traditional suburban backyard 3 – traditionally a safe place where children could engage in imaginative and open-ended play away from the constant supervision of adults. The problem is twofold – firstly, children often do not have access to public or private outdoor environments where they can play. Secondly, even when these spaces are available for children, many parents are reluctant to let their children play in them out of concerns about their safety.

In relation to this, some commentators have expressed concerns about society’s tendencies towards indoors play. US child advocate and writer Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods discusses what he terms “nature deficit disorder,” 4 or a growing disconnection of children from the natural elements and processes that make up the physical world around us. Interestingly, he connects this to the future sustainability of the planet, where if children have no knowledge of the natural world, why would they care about what happens to it? Given these concerns, the question for designers is: How can we create optimum outdoors environments for play in a society where fear, control and regulation of play appear to be the norm?

There is some evidence that designers are beginning to challenge traditional modes of playground design by extending the role of playspaces to include a range of different social agendas. Here, two trends are discernible. The first involves the rediscovery of the adventure playground, which is once again gathering momentum in reaction to the over-controlled and directed nature of contemporary play environments. The second involves the potential for hybridization of playspaces – a situation where the spatial boundaries between adults’ and children’s activities are blurred as adults are increasingly invited into play domains, while opportunities for play expand into the built environment.

Revival of the ‘adventure’ or ‘imagination’ playground

The adventure playground has long been seen as a design type that encourages creative and imaginative play in outdoors environments; however, it has recently been revived as an idea in relation to debates about the over-directed nature of children’s play. Initially developed in the 1930s as a means to provide children from poor urban neighbourhoods with opportunities for play, the first adventure or “junk” playgrounds were developed by the Danish landscape architect Carl Theodor Sorensen, who noticed that children were more interested in playing in the raw vacant blocks and city streets that surrounded their homes than in the polished and structured playgrounds he had designed.

Adventure playgrounds differ from traditional playgrounds in that they emphasize the use of recycled, natural or found materials rather than manufactured equipment, and have a relatively flexible or informal layout. The broad aim is that children create their own games, physical experiences and scenarios while programming the site according to their own agendas. Significantly, adventure playgrounds often incorporate some form of adult supervision, which allows for active but safe play such as cooking, growing plants and caring for animals as well as the use of movable tools, toys and scrap materials that can be packed away at the end of a session. While adventure playgrounds promote more imaginative and open-ended play than is currently found in conventional playgrounds, their relatively messy appearance makes them an unattractive proposition for many communities unfamiliar with their purpose. Furthermore, the provision and administration of supervised playgrounds is often not an option for smaller local playgrounds that are funded by council budgets. As such, there are currently only five adventure playgrounds in Australia. Nevertheless, these playgrounds are extremely popular and play a vital social role within their local communities. A good example is Skinners Adventure Playground in South Melbourne, which caters primarily to disadvantaged children living in nearby public housing.

Imagination Playground by David Rockwell and KaBOOM!, NYC.

Image: Frank Oudeman

The idea of “loose parts” or the use of movable playground components is one way in which open-ended play can be designed into existing playgrounds while maintaining the structured look of traditionally designed spaces. Architect David Rockwell and play organization KaBOOM! have used this idea in their collaboration on the new Imagination Playground in New York City. Their development of a “playground in a box” involves a kit that can be moved or retrofitted to different locations and which contains tools, construction materials and found objects that could be used within endless imaginative play scenarios. The first Imagination Playground was opened in 2010 in the seaport suburb of Burling Slip in New York City.

In Australia, this concept has been developed by not-for-profit organization Play for Life, with its use of shipping containers or “pods” that can be moved around different sites, including schools. As its website claims:

“The Pod is a modified shipping container, filled with high quality “loose parts” play materials. Clean, safe scrap, otherwise destined for landfill, is carefully selected and recycled for use in the Pod. This can include anything from old car tyres and steering wheels, to cardboard tubing, milk crates, used keyboards and telephones, fabric and dress-ups.”

The concept of loose parts is essentially about providing flexible components for play, without directing what that should actually involve. As such, the idea could also extend to the types of materials and spaces that designers create within playspaces. For example, sand and water features, multifunctional elements such as logs, boulders, cubbies and mounds, and materiality based around sensory experiences all provide endless opportunities for play. Essentially, the move back towards the adventure playground represents a growth in adults’ trust that children know how to play and that they will play instinctively if provided with the right tools and a safe environment to do it in.

The hybridization of playspaces

It is also worth discussing the broader role of playspaces in the built environment. Concerns about child safety have often resulted in the playground being cordoned off as a place exclusively for children and their parents. Adults are rarely encouraged to be in playgrounds unless they are performing a supervisory role; in fact, the very presence of adults in playgrounds is viewed with some suspicion. This is problematic as it sets up a division between adults and children and contributes to misunderstandings about what play actually involves.

Casey Fields playground in Melbourne by the City of Casey.

Image: Drew Echberg

Recent examples of innovative design in Australia provide us with a focal point to reconsider the possibilities embedded in playspaces. As places to gather, celebrate, educate, connect communities and perform environmental roles such as water collection and treatment, playspaces become important pieces of urban infrastructure where play becomes the locus for broader social goals. Three recent large-scale play projects in Sydney typify this approach: Blaxland Riverside Playground (JMD Design), Darling Quarter (Aspect Studios) and Lizard Log, formerly Pimelea Park, (McGregor Coxall/Fiona Robbe). In all of these designs, the playspace is not an isolated space, but is part of a wider spatial network including Sydney Olympic Park, the Darling Harbour entertainment precinct and Western Sydney Parklands respectively. These playspaces enable exciting and innovative play experiences, but are also important drawcards that encourage large groups of adults to come and dwell within the public domain.

Landscape architect and playspace designer Fiona Robbe suggests that these might be called “family entertainment venues” rather than playspaces. They are places where families, community groups and friends may gather for long stretches of time for activities such as picnics/barbecues, celebrations, reunions and entertainment. Given these multiple roles, amenities such as seating, barbecues, shelters, extensive areas of open grass and toilets become vital to catering to large groups.

While adults are increasingly being invited into the space of the playground, play is less often seen as an important component of other built environment contexts. The very fact that we need playgrounds suggests that play is seen as inappropriate in other spatial domains – think of the disapproval directed at groups of youth for loitering in public spaces. In fact, many of the earliest playgrounds were developed in order to encourage children playing in the streets to “go somewhere” – an idea that suggested an interest in children’s welfare but that also had the effect of putting them out of sight and out of mind.

Lizard Log by McGregor Coxall and Fiona Robbe Landscape Architects.

Image: Simon Wood

While there are many examples of playful public space designs – the mounded hills and sculptural installations at Birrarung Marr in Melbourne, the colourful and bold design of Room 4.1.3’s Garden of Australian Dreams in Canberra, and the AILA’s recent Street Works installations throughout the streets of Sydney – the deliberate inclusion of play opportunities within public space design is less common. Often, public spaces are informally adapted as play environments, as anyone who lives in Sydney can attest – children’s use of the concrete “slides” on the Sydney Opera House forecourt; the regular invasion of St Mary’s Cathedral forecourt by teenage skateboarders. Considering that children have equal rights to public space, it is particularly important for designers to think about how both children’s and adults’ play can be included into a range of public areas beyond that of the formal playground zone.

Overall, playspaces are essential in that they provide opportunities for children to test and develop a wide range of skills in a safe, child-directed environment. In an increasingly technological society, they also have an important role to play in exposing children to outdoors settings and the natural processes that occur within them. While manufactured equipment provides a broad range of physical and social experiences and will certainly remain popular components of contemporary playspace design, it is also vital for designers to consider how unstructured and open-ended imaginative play can be inserted into playgrounds.

Recent examples of play design in Australia indicate an exciting expansion of the traditional playground to incorporate social and environmental functions while connecting with broader open space networks. Potentially, the next step is to bring play out of the playground to permeate the built environment in unexpected and delightful ways. Applied to many of our ordinary and drab urban spaces, the “temporary world” of the playground could be a wonderful generator of vitality in the built environment for children and adults alike.

David Eager – Associate Professor in risk management at the Faculty of Engineering, the University of Technology, Sydney

“As the only engineer on the Australian Standards Committee for Children’s Playgrounds I am often misrepresented as being the person responsible for taking the fun out of playspaces.

“Those who have worked with me or attended the University of Technology, Sydney playground inspector training or design courses will know that this statement is incorrect.

Casey Fields playground in Melbourne by the City of Casey.

Image: Drew Echberg

“Society tasks engineers with the role of risk management. We design and build things that society expects to work each and every time they are used. We take a risk each time we release new technology and yes, sometimes we get it wrong. When we do get it wrong, it can result in death. Risk management is not about risk aversion; it is about embracing and controlling risk. In the context of playgrounds it is about enhancing childhood experience and maximizing childhood development while applying a strict hazard-removal filter. Children need and must be exposed to managed risk as a normal part of their development.

“Standards provide rules for hazard removal and the implementation of acceptable risk tolerability levels, i.e. As Low As is Reasonably Practicable (ALARP).

“There are fundamentally two approaches to the application of risk management. The first is a behavioural-based approach, while the second involves the application of a hierarchy of risk controls. Since playgrounds are considered unsupervised, we need to rely on a hierarchy of risk control that is embedded within the playground design that is codified within the Playground Standards.

“As we say in the foreword to AS 4685, the primary purpose of a playground is to stimulate a child’s imagination and provide excitement and adventure in safe surroundings.

“It is my opinion that it is the responsibility of the landscape architects and engineers to work in harmony and use the latitude embedded in the Playground Standards to make our playspaces as exciting and simulating as the budgets allow.”

Mary Jeavons – director, Jeavons Landscape Architects

“Decades of research has shown that children need opportunities for unstructured free play.

“The outdoor spaces that best support children’s activities may well include play equipment, but it is highly likely that they will also include something that is a little rough and open-ended – some loose parts that children can fiddle with, a special tree they can climb, some branches that can be made into a cubby, some plants with leaves or flowers that can be collected or a big rock that can become a ship or an island on demand. Or simply some dirt, sand or pebbles.

“It is often hard to successfully include such ‘un-designed’ elements into public places, schools or early childhood centres. It requires strong leadership and advocacy on behalf of children to provide planting that is specifically for their use, to provide sand or large river pebbles for them to move around at will, or to hold fast against residents’ complaints about mess.

Lizard Log by McGregor Coxall and Fiona Robbe Landscape Architects.

Image: Simon Wood

“Long considered subversive, the activities of children have, since the late 1800s, been frequently viewed as something to be tamed and controlled; to this day it takes a strong parks manager or school principal to allow a fort made of branches to remain in a playspace.

“It also costs a lot for local governments to maintain planting for play or to keep an eye on a park with sand and loose materials.

“And it is asking a lot that a landscape architect might consider leaving some stretches of space relatively ‘un-designed’ but with a rich palette that invites these subversive child-directed activities to flourish. Yet this is what we must do as designers.

“As 89 percent of Australians now live in urban environments, outdoor play for most children will take place in spaces that have been designed. By us.

“This provides some major challenges for our profession: to overcome the temptation to over-design public space; to research and understand the importance of unstructured free play to children (even if this challenges our sense of control); to recognize and advocate for children as legitimate users of outdoor space; and to hold firm against over-sanitizing our parks, open spaces, school grounds and early childhood centres.”

The author would like to acknowledge Fiona Robbé for her expertise and insights, which aided in the compiling of this essay.

1. J. Huizinga, Homo ludens (trans. Man the Player) (London: Routledge, 1938).

2. G. Hayward, M. Rothenburg and R. Beasley, “Children’s Play and Urban Playground Environments: A Comparison of Traditional, Contemporary, and Adventure Playground Types,” Environment and Behavior, vol 6, 1974, 131–168.

3. T. Hall, The Life and Death of the Australian Backyard (Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing, 2010).

4. R. Louv, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2005).

Source

Practice

Published online: 29 Apr 2016

Words:

Emma Sheppard-Simms

Images:

Drew Echberg,

Frank Oudeman,

Jason Daley,

Simon Wood,

courtesy of CPG Australia.,

courtesy of CPG Australia.

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2012