Sydney Harbour’s headlands are one of the most enchanting elements of its urban landscape. The design of the new Barangaroo Point park is located on one of the most central, the headland adjacent to the Sydney Harbour Bridge’s Dawe’s Point. In the 19th and 20th centuries the headland was progressively obliterated to make way for industry until ultimately there was little left except for a vast concrete hardstand wharf. In 2006, the East Darling Harbour International Urban Design Competition was held to generate ideas for the large site.

Sketch by Craig Burton suggesting the original club cape landform.

Image: Courtesy CAB Consulting

As a result of this competition, a vision for a reconstructed headland crystalized. Its genesis was clear in the March 2006 jury report, which recommended the inclusion of “…a natural headland form which touches the water at the northern end of the site….[and a] large northern cove directly behind the headland to further define the headland.” The headland and cove were elements included in the Rogers/Schwarz/Lippmann/Lend Lease highly commended scheme and represented a departure from the winning scheme by Hill Thalis/Irwin/Berkemeier.

As Barangaroo Point nears completion, the boldness of the vision to reconstruct the original headland is evident. The reconstructed headland is monumental. Peter Walker, the lead landscape architect for the project, suggests it should have the “qualities of walking on an ancient headland.” But in its newness, the primeval qualities Walker refers to are difficult to sense. When the final construction phase comes to a close and it is open to the general public, will the casual visitor know they are walking on a reconstructed headland? Will the park feel indigenous? And should visitors know what they are walking on? Is authenticity important?

During 2009 and 2010, the Barangaroo Delivery Authority assessed expressions of interest (EOI) submitted by high-powered design firms from around the world for the design of a headland park at the northern end of Barangaroo. The selected design team included Johnson Pilton Walker (JPW), Sydney, in association with Peter Walker and Partners Landscape Architecture (PWP), Berkeley, California, and the Sydney-based historian and curator Peter Emmett.

Following their successful EOI, the team was formally engaged by the Barangaroo Development Authority and handed the brief. Remarkably, the brief had changed from the initial EOI document. Paramount among the amendments was the inclusion of an 18,000-square-metre “cultural facility” (in addition to a concealed car park for 300 cars). The design brief also called for the maximisation of the “impact and value of the existing sandstone escarpment” that remained after the headland was removed in the 19th and 20th centuries. The design team’s initial vision for both of these elements would be compromised in the final design.

The cultural facility was to be naturally ventilated and to use the interface between the new headland park and adjacent Millers Point as a light shaft.

Image: Courtesy JPW

On winning the contract, the PWP and JPW design team studied the morphology and characteristics of Sydney’s headlands using old maps, paintings and historical documents and made a close investigation of similar headlands around the harbour. Imaginative studies by Sydney experts such as Craig Burton informed the design explorations. During these early stages, JPW came up with the idea of using the northeast-southwest sandstone bedding and the weathering patterns found on Sydney’s exposed sandstone escarpments to structure the design. This concept is illustrated in a series of evocative images demonstrating the potential configuration of sandstone at Barangaroo Point. Such patterns can be found throughout Sydney and can be seen very clearly at Laings Point Reserve, Watsons Bay and Cannae Point on Sydney Harbour’s North Head, close to Manly.

After these initial conceptual sketches, the design team developed practical methods for evoking the tessellated bedding and weathering pattern. Extensive excavations of the Barangaroo site for new bays and building foundations revealed enough bedrock was available to cut over 10,000 rectangular pieces for use in the headland. The team explored different methods for finishing the blocks, such as the use of high pressure water jets to create eroded wave patterns. Such finishes were eventually discarded in favour of a raw, freshly quarried texture. The configuration of the stones was designed to read differently from different vantage points, which indeed they do in the realised project. From ground level, the blocks appear more irregular and uneven while from higher vantage points they appear stylized and geometric in a play upon made/unmade and manufactured/natural tensions.

On discovering that the cultural facility was to be a major component of the design, JPW set about forming an architectural team, in addition to their landscape team, to tackle it. The JPW architecture team, led by Kiong Lee, were intent on reflecting the tessellations being developed for the foreshore areas within the subterranean space of the new cultural facility. Inspired by the geological continuity that landscapes have with caves, they inverted the foreshore tessellations, integrating them with a diagonal grid of column and beams, to create a system that produced a dramatic stepped profile. These tessellations corresponded with the need for a variety of soil depths above, while creating visually striking ceiling modulations in the subterranean cultural space below. The structural system was to provide an enormous cavernous space that could offer the necessary flexibility to accommodate diverse cultural uses and shafts of natural light. In essence, the space would share the same structural language as the surrounding landscape of the park.

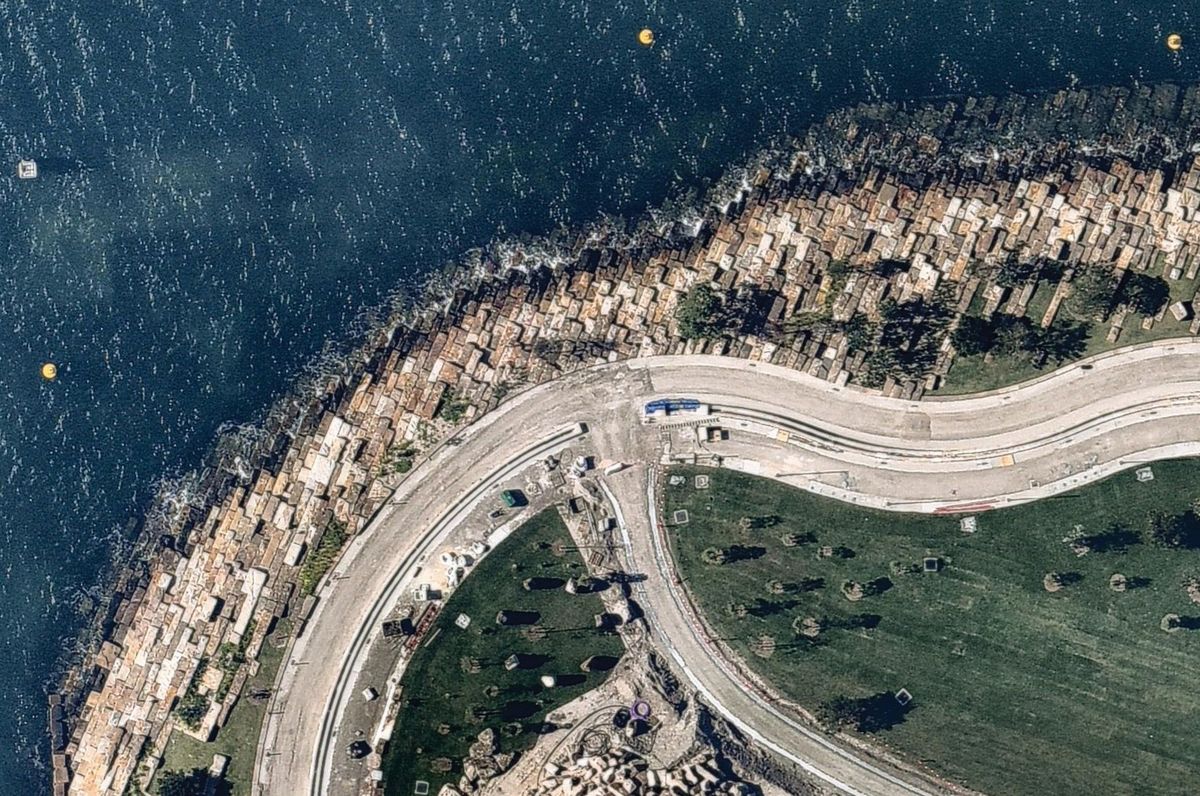

Aerial photograph of Greens Point Reserve (top) and aerial of Barangaroo Point’s final built landscape (bottom).

Image: Courtesy JPW

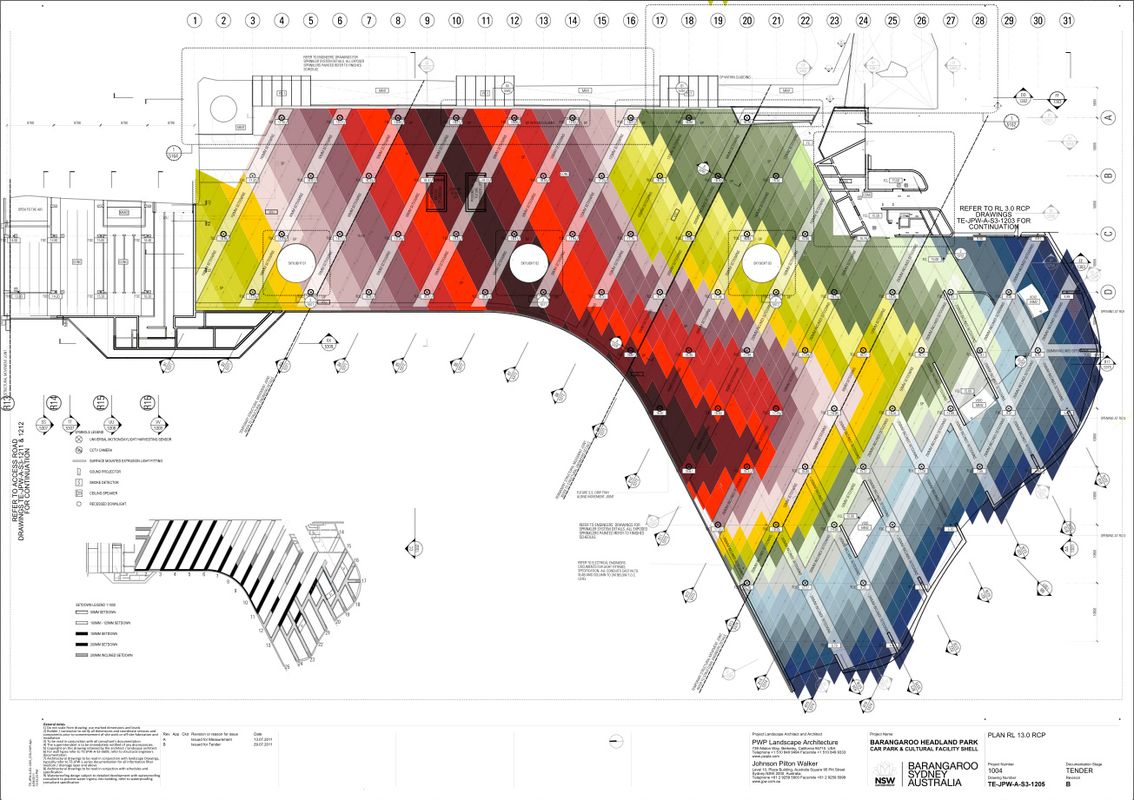

The system would effectively establish seamless design continuity between the outside and inside cultural spaces. The cultural facility was also to be naturally ventilated and to use the interface between the new headland park and adjacent Millers Point as an elegant light shaft, reflecting light to orientate visitors entering the space. Visualisations of the entry to the cultural space demonstrate the clarity of the idea and the compelling resonance with rocky overhangs and caves found throughout Sydney’s sandstone country. An example of the tessellated diagonal column and beam structure can be seen in the images above. The various colours JPW uses in this drawing are a code for the proposed topographic modulations of the interior space, and bring to mind the ubiquitous structural logic of the Sydney opera house with its precast system.

The Barangaroo Delivery Authority did not embrace this sophisticated fusion of space, form and materials and following production of a full set of tender drawings, it was left to the bidding contractors to bring their own supporting consultants. The builders for the project, Baulderstone/Lend Lease, replaced JPW with their own novated architects on the design of the cultural facility and engaged JPW as construction landscape architects in a more technical role. PWP were re-engaged as advisors to the BDA, leading the landscape design. The engineers for the project, Robert Bird Group, were also part of this reshuffle of roles.

These changes weakened the integration of architecture and landscape expertise and fragmented the comprehensive design vision. JPW’s cultural facility has been replaced with a utilitarian box with its function yet to be determined. Equally, the entrance to building, unfinished as it is, promises none of the verve of the JPW scheme and is unimaginative and boxy. Usually, value engineering is used as an excuse for such impoverished outcomes, but JPW are convinced that their scheme could have been delivered cost effectively at a comparable price to the subsequent engineering system adopted.

The division of the disciplines of architecture and landscape, in a structure that so evidently calls for their close integration, is a major loss for Sydney as a cosmopolitan city. Members of the subsequently disbanded Design Excellence Review Panel, for Barangaroo, suggest that this split at a critical moment between concept design and construction reflects the divisive policies of the Barangaroo Delivery Authority and the inadequacy of current contract structures in delivering best-practice design outcomes.

What has Barangaroo Point delivered? Surprisingly for such a new park, it is the plants that are the standout feature. The species selection is meticulous and botanically expansive. There are over 70,000 plants in total, with some never before used in a horticultural setting. Stuart Pittendrigh, responsible for the planting, remarks that the “growth rates have been spectacular” and less than 1% of specimens have been lost during their establishment. These outstanding growth rates can largely be attributed to a rigorous technical approach to phosphorous, pH and permeability or drainage, established by soil specialist Simon Leake.

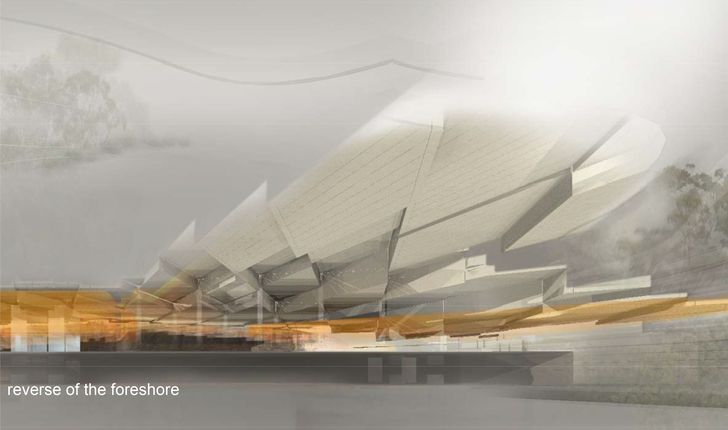

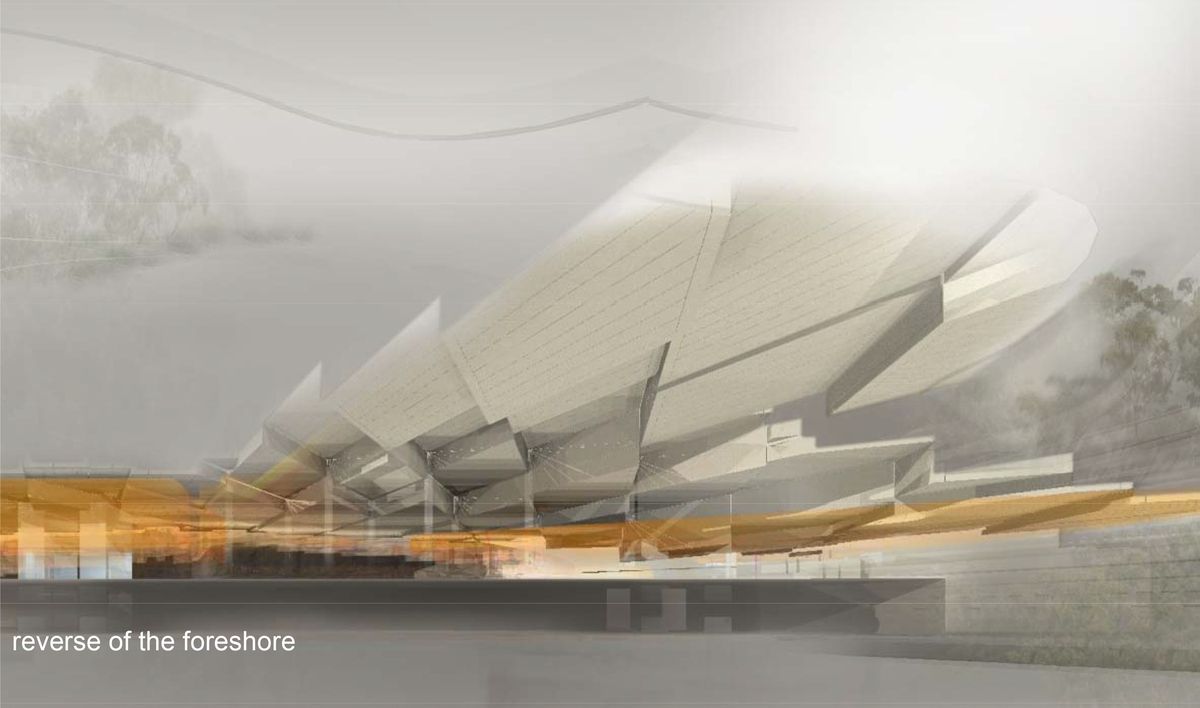

Rendering of proposed cultural facility showing the inverted foreshore tessellations, integrated with a diagonal grid of column and beams.

Image: Courtesy JPW

For a park that draws so much inspiration from natural forms, though, the over-all design outcome is mannered; it certainly lacks the subtlety, scale shifts and variation evident in naturally bedded sandstone. This is in part a result of the construction technology, with the dimensions of the sandstone limited by the cutting equipment. Although a major technical feat, the sandstone geometries do not effectively suggest the idea of the greater tectonic forces that shaped the original headland. Much as the detailing of a building can mask its construction technique, the sandstone is a veneer. One reason for this is the retaining systems that shore up the steep slopes are constructed of different materials and indifferent structural systems that do not relate to the foreshore walls and path systems. Although the park is awash in sandstone, the 10,000 individually crafted blocks are situated alongside an eclectic mix of materials. The detailing integrates diverse juxtapositions of bluestone, concrete, bitumen and corten. Rather than a tight integration of material, structure, and pattern, these aspects of the park’s design correlate loosely.

Barangaroo Point foreshore, as complete.

Image: Courtesy JPW

Perhaps most significantly, the realised design diminishes the existing sandstone escarpment. It bridges across the light shaft left between the authentic sandstone cliff and the re-created headland with concrete beams, turning what could have been an elegant architectural element under the JPW scheme into a crude vent. The construction of a headland and the conservation of the sandstone escarpment as an integral and authentic element of the design were entirely compatible objectives (as demonstrated in JPW’s early drawings), which have not been resolved. The Burra Charter, a document by the Australian branch of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) now adopted internationally as best practice in the treatment of significant cultural places, provides a useful guide in the treatment of cultural heritage: “The traces of additions, alterations and earlier treatments to the fabric of a place are evidence of its history and uses which may be part of its significance. Conservation action should assist and not impede their understanding.” In other words, history is not a destination but rather in “the making”.

The promised sophistication of early concepts to fuse space, form and materials through a common structural language is unfortunately absent in Barangaroo Point as realised and the story of past and present is all the weaker for it.

Barangaroo Reserve opened to the public on Satuday 22 August, 2015.

Disclosure: Scott Hawken was part of the Hill Thalis Urban Projects, Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture and Paul Berkemeier Architecture team that won the International Urban Design Competition for Barangaroo. His involvement with the team ended in 2006, when he commenced work on a PhD in archaeology, at the University of Sydney.