It’s hard to picture Melbourne in 1983, when Professor Rob Adams first arrived to join the project team tasked with writing the City of Melbourne Strategy Plan (1985). Thirty-four years on, Melbourne has flourished and the City Design team that he leads at the City of Melbourne has accumulated 160 awards and delivered a suite of key policies and built projects, including the Postcode 3000 planning policy, Birrarung Marr, the Urban Forest Strategy, Swanston Street and the Places for People study.

Adams had arrived in Melbourne with a growing sense of disquiet about the types of places being built. A study tour of Europe taken in 1969 for a fourth-year architectural research project called “Town Planning in Scandinavia and the Hill Towns of Italy: a comparative study” catalysed his changing attitude.

“I went to Scandinavia and looked at the satellite towns being built and they felt soulless. Then as I travelled through Germany and saw some of the big architectural names I didn’t get any more satisfaction that we were actually building stuff that was nice to be around,” says Adams.

The less obviously designed Italian townships, where people lived their daily lives out on the street, captured his attention. “I started to ask, how come we’re not designing cities like this? It was formative for me because I realized my architectural education had neglected any discussion about urban design – it was all about buildings, objects and beauty.” That realization signalled a shift toward urban design. “It didn’t stop my passion for architecture; it made me look at architecture in a different way,” he says.

“[In Melbourne] I saw what Ieoh Ming (“I. M.”) Pei had done in Collins Place, in blowing apart that piece of city by introverting the building and putting up blank street frontages. A lot of people still admire these star architects, but don’t critique them on the basis of how well they’ve integrated [their work] with the city. And that’s fundamental to the way I look at cities – [architecture needs] to fit with the local character.”

In Melbourne, the timing for the new strategy plan was serendipitous. Adams found a growing community of built environment professionals who were mobilizing to protect the city’s cultural fabric.

“People like Ruth and Maurie Crow in North Melbourne [A Plan for Melbourne, 1969–1972] and Evan Walker with the Collins Street Defence Movement were asking: What do we do to make sure we don’t lose Melbourne as we know and love it?”

A lack of ready money meant that the strategy “had to be about incremental change and how to embed actions that cumulatively reinforce the existing character of that place. What they were asking for was a twenty-four-hour, mixed-use city that looked and felt like Melbourne. Defined like that, it’s not a difficult task.”

Adams regrets that built form controls like setbacks, such as this one at 101 Collins, have not been adhered to in recent years.

Image: David Hannah

It’s this ability to find the right questions combined with a collaborative approach that has worked so well for Adams, exemplified in Council House 2 (CH2), Australia’s first building to be awarded a six-star Green Star design rating. Designed using the charrette method (from the French term meaning “to draw at the last moment”), the building showcases what a healthy, sustainable building and workplace can achieve. And while the building has been criticized for costing 20 percent more than an ordinary commercial building, for Adams, the 80 percent energy savings combined with increases in staff productivity (which save around $2.4 million dollars a year in staff costs) provides justification aplenty. It also demonstrates the design philosophy that underpins the City Design team’s approach.

“This building is a microcosm of how we work. We’ve got a multidisciplinary office and we try not to break those down into teams, we work collaboratively and that tends to generate interesting results.”

Where key strategies have worked to gently revive the CBD, Melbourne is now in a period of radical change, marked by a number of big infrastructure projects, including the Metro rail tunnel, the Southbank Boulevard and Dodds Street redevelopment and a $250 million revamp of the much-loved Queen Victoria Market. It’s the last that has sparked the most angst, meaning years of negotiations and consultation to try to reassure the community.

The City of Melbourne’s $250 million plans to revamp the much-loved Queen Victoria Market have sparked much debate.

Image: Andrew Curtis

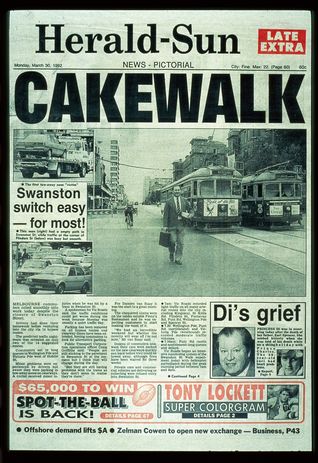

The front page of the Herald Sun on the day that Swanston Street, Melbourne’s main thoroughfare, was closed to vehicle traffic in 1992.

“Many of our strategies are about trying to illustrate to people what the future will look like,” he says. “Swanston Street was a big turning point. To sit in VicRoads’ office on the morning of its closure, to see the city just find its own pattern and not close down … the journalist next to me said, ‘Oh, this is a disaster – we’ve written a headline for the midday paper and it’s “Traffic Chaos.”’” (The headline that eventually came out was “Cakewalk.”)

“We had taken something and worked with all the agencies and shown that you could change things without the world coming to an end.”

Fast-forward to now, and it’s a similar challenge. “You can see the battle we’re having with the Queen Victoria Market because the stakeholder base is really varied, there’s a lot of emotion attached. Having that debate and trying to ameliorate everyone’s fear is very much part of the job.”

When it comes to championing better cities, Adams acknowledges it’s a tricky dance (he famously calls himself an urban choreographer) that must include so many players: developers, politicians and the citizenry.

“That to me is the fundamental role of local government, how you manage the expectation from the community that we will make their places better. Just saying ‘this will create more jobs’ is important, but it’s not the whole story. Sometimes lost in the one-liners is the understanding that the real value of a city comes in taking a holistic view. If you incrementally change the city for the worse over time, you lose value for everyone – the developer and the community. All assets become devalued.”

Curiously, Adams’ proudest achievement is also tangled up with “the one that got away.” And that’s the Postcode 3000 planning policy, which aimed to bring a residential population into the city.

For Adams, Postcode 3000 stands for “having the courage to say we need eight thousand people in the city in the next fifteen years, and having no idea of how we were going to do it, but setting out to discover how that would happen, delivering on it and then seeing the city change. It taught me to be less frightened of setting targets.” It’s an approach that remains relevant for facing contemporary challenges.

“In Postcode 3000 we took old buildings and repurposed them into residential [developments]. That goes to the core of what we need to do in the next thirty years – we need to repurpose our city. I find that an enormously exciting challenge. Tied up in that little phrase is a whole philosophy around how you get things done. And sometimes it’s not about what you do, but what you encourage others to do.”

An unforeseen consequence of the initiative was the change in dynamics of city development. “If you don’t hold to the principles of built form controls, like setbacks at designated heights, every single site in town becomes a development site. So this hugely positive thing about bringing back a residential population has started to erode the thing you love.” But it hasn’t got away completely, he says. “We’ve just caught it by the tail and are trying to pull it back in!”

A current project that the City Design and Projects team is working on is the redesign of Southbank Boulevard to provide more public open space in one of the densest areas in Melbourne.

Image: Scenery

When it comes to outlining his lessons for the future, Adams is frank. “Governments have contracted out their intellect. Through economic rationalism we think we can get rid of government architects and public works departments, and we can just buy in consultancies. But with every consultant comes a different idea in a small package in a single point in time.” By doing some of the work themselves governments will understand the nature of the contracts that they need to write. “One of the reasons I’ve stayed in local government is that to have an in-house capability – that actually builds and designs stuff, and provides policy advice – means you get good policy advice.”

The other key challenge is to produce robust strategies that can survive political turmoil. “Our strategies need to have longevity; they need to communicate well and to have clear objectives that are contextualized.”

Climate change is an example, in that the problems sometimes seem insurmountable. But to break the juggernaut down into manageable categories based on three geographic areas – cities, rural areas and oceans – makes finding solutions possible. “You ask: How do you deal with climate change in cities, in rural areas and in oceans? Dealing with climate change in cities, for example, is easy. You plant more trees, capture water, change buildings to be more efficient and you start using renewable energy. None of those things is mystifying.”

In all, Adams is proud to have “encouraged hundreds of people to think about a city in a slightly different way. Young professionals have come through here and they’ve produced great things. It’s not individually what I’ve produced, but I hope I have helped to make design important in the realization of the city.”

Source

Practice

Published online: 3 Apr 2018

Words:

Lucy Salt

Images:

City of Melbourne,

David Hannah,

Jessica Shapiro/Fairfax Syndication

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, November 2017