Prompted by a media flurry focused on unhappy traders, I visited Prahran Square on a mild and sunny late afternoon in February. The complaints were reminiscent of early moments in the life of Federation Square: certain expectations about public space weren’t being met (where were the trees and grass?) and many were prepared to condemn the new space before it had time to embed in our collective cultural psyche. But less than a generation after these criticisms were levelled at Federation Square, attempts to re-work a small part of it were furiously and successfully opposed by hundreds of thousands of Melburnians. My curiosity was piqued. What qualities of this new public space in Prahran were being questioned, and what demands does the design make on people’s sense of place? Might locals build bonds with the space that will motivate them to oppose future change? And, picking up on a reported remark from Jill Garner, Victoria’s government architect, that Prahran Square is a “model” for public space, what typological implications might it have for Australian cities?

Both the promotion and the commentary for this project foregrounds the figure of 10,000 square metres of new public space – “larger than Federation Square!” – but a key design move has been to produce a suite of carefully wrought and detailed smaller spaces, each with a distinct character. The brief called for a place of diversity to attract locals and those from further afield: passive recreation for kids and adults, somewhere for neighbourhood residents to relax and a singular event space for markets. A single cafe was to service the square, although additional commercial spaces now face the four surrounding streets. This has been achieved by flipping up the ground plane on three sides to create a shallow amphitheatre with single-storey street walls facing outwards. It is an urban form with no back, only frontages, interiors and exteriors. This excludes most of the commercial elements from the square. At the time of my visit, none of the tenancies, or the square’s cafe, were occupied, except for a temporary installation, which was closed.

Traversing the site, I first entered at the intersection of Izett and Chatham Streets, the so-named Greville Corner, which acts as one of four “antechambers” welcoming pedestrians to the square. The four corner spaces vary from about 300 to 500 square metres, about the size of many pocket parks on corner blocks. However, these paved urban spaces – enclosed by strong vertical edges on two sides with indeterminate boundaries to the streets they join – become free-form, laneway-like passages made habitable with built-in ledges, seats and tables integrated with planting beds.

The square’s flipped up edges create laneway-like entrance ways; ledges and seating are integrated with planting beds.

Image: Christian Riquelme and Fabio Borges (Aspect Studios)

The surface-level design organizes pedestrian flows along the new street walls and across the square from the corners. A fifth route to the square is via a covered passage halfway along Cato Street with access to public bathrooms and car park lifts. In a significant improvement on the brief, vehicle access to the parking levels has been limited to a single portal on Izett Street, while Wattle Street is now fully pedestrianized and Cato Street has extensive pedestrian priority. Vehicle traffic has thus been removed from much of the public realm, creating a far more universally accessible ground plane.

The above-ground elements of the square are organized through a classic nine-square format: four corner spaces, four edge spaces between them and a central space, all calibrated to context. Each of the corners is intended to relate to a significant local character element – the other three being Prahran Market, the retail precinct at the Commercial Road-Chapel Street corner, and the Prahran Town Hall civic precinct. The square has been shaped in part by drawing sightlines from the nine-part grid to well-known Prahran landmarks in the broader precinct, a gesture to pre-cartographic navigation. Many of the taller landmarks are currently visible across intervening rooftops, but future development around the edges of the square will need careful regulation to ensure sightlines remain, even though additional views are created by the square’s elevated edges.

Planted with Koelreuteria paniculata (golden rain tree) and Anigozanthos ‘Gold Velvet’ (yellow kangaroo paw), the terraces offer flexible seating options for visitors.

Image: Christian Riquelme and Fabio Borges (Aspect Studios)

Despite the pleasant weather, there weren’t many people at the square during my visit. But there were even fewer in the surrounding streets and in nearby Grattan Gardens – the quintessential “trees and grass” it is asserted Melburnians want for their public spaces. A month before stage three lockdowns would be introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, public life had already begun to thin out. Still, a steady flow of people walked through the square on local journeys. Others sat or lay on the grass, sat on the terraces reading, eating or sleeping. Some sat at the tables within the sensory garden facing the not-yet-open cafe. Skateboarders and BMX cyclists came exploring, enjoying the challenges posed by the fat white strip that runs around the entire space, marking the boundary between the nine parts.

The five access ways into the square reinforce the sense of an amphitheatrical arena, conjuring overlapping impressions of relaxation, entertainment and sport. Just a few people create the sense of participating in a theatrical event. The interior is almost a hectare, yet the space is sufficiently intimate to be ambiguously social rather than anonymously distant: people can see what others are up to and get a sense of who else is around.

Prahran Square offers a diversity of spaces for different users, including play areas for kids, a sloping lawn for relaxation and a paved space for events.

Image: John Gollings

Prahran Square poses questions about people’s expectations regarding public space. It is not a public square in the European tradition, with a strong commercial or civic presence. Instead, it offers another kind of “third space” where being together and being alone can be done outside norms of market and ceremony. Crucial to this, of course, is that the square is a public project, funded and built by the council for its community. It needs to be noted that most of the $64 million was spent on putting the parking underground in a place served by three trams, a busy rail line and an increasing density of local population. But this irony aside, Prahran Square challenges the sensationalist rhetoric surrounding its development, launch and critique, which has focused on it being a means to the commercial success of the Chapel Street precinct.

When more mature, Corymbia citriodora ‘Scentuous’ (dwarf lemon-scented gum) plantings will shade the square’s expansive lawn.

Image: Christian Riquelme and Fabio Borges (Aspect Studios)

Beyond its appeal to diversity and its publicness, however, it’s difficult to see how Prahran Square might offer a new typological model for Australian cities. Huge capital investments in undergrounding parking are unlikely to be viable in most of the many other places where more public space is sought. Tactical approaches that re-organize access to surface parking according to time and occasion could be equally effective: markets, festivals and concerts have long occupied public parking lots, some have become iconic and regular. Incrementally re-purposing small numbers of car spaces for bike parking, shaded seating, planting and mobile food providers can provide enormous amenity benefits, and is fast, relatively inexpensive and adaptable according to need. If Prahran Square hadn’t required any parking at all, what would $64 million have allowed for in terms of shade structures, the most obvious omission from the design? All up, this model is a high price to maintain car-dependency.

The desire for more and better public space in Australian cities must be disentangled from market imperatives if we are to create spaces for being, on terms beyond monetary exchange or civic duty. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, Prahran Square has provided the kind of public space required for this strange new mode of intensely localized urban living. In an increasingly uncertain future, public spaces that can cater to unforeseen demands will prove to be among some of our most valuable assets.

Credits

- Project

- Prahran Square

- Design practice

- Lyons Architecture

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Aspect Studios: Kirsten Bauer, Matthew Mackay, Tim Fowler, Dermot Egan, Warwick Savvas, Christian Riquelme, Marti Fooks, Nick Griffin, Duyen Nguyen, Blake Farmar-Bowers

- Design practice

- ASPECT Studios

Australia

- Consultants

-

Landscape architect

ASPECT Studios

Principal consultant Lyons Architecture

Project manager AECOM

- Site Details

-

Location

Prahran,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2019

Design, documentation 12 months

Construction 24 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

City of Stonnington

Source

Review

Published online: 7 Nov 2020

Words:

Ian Woodcock

Images:

Christian Riquelme and Fabio Borges (Aspect Studios),

John Gollings

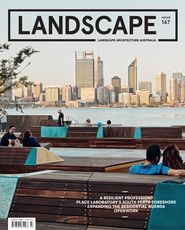

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2020