“There are many words for ‘I’ in Japanese,” says Yu Nakai Sensei, professor at Tokyo University’s Civic Landscape Design Lab, during a presentation to visiting students.

“The word changes depending on … where you are and who you are with. Family, friends, at work, meeting someone, so many different [versions of ‘I’]. So you can see how there is a difficulty of individual identity in favour of a local community identity, and how in light of this, relationships between people and place become extremely important in the understanding of oneself.”

In late 2016 a group of students from RMIT University’s Landscape Architecture and Master of Disaster, Design and Development programs that travelled to Japan as part of a research program coordinated by Marieluise Jonas, senior lecturer in landscape architecture RMIT University, in collaboration with Masao Hijikata Sensei, lead consultant of disaster research at Waseda University. The Affective Geometries design research studio saw us investigate post-2011 tsunami Japan and contribute to the sensitive rebuilding of devastated towns.

A flowering garden is all that remains of this home near Hashikami beach.

Image: Hayden Matthys

Before travelling to Japan we had spent the past few months working on designs for a designated memorial park for the tsunami-hit town of Hashikami, in the Sannohe District of south-eastern Aomori Prefecture in the Tohoku region. Nakai Sensei’s words articulated an idea that I had previously taken for granted, something that is often preached but not practiced in the design professions – the importance of working with the identity of place.

In Tokyo we toured the Japanese landscape: we saw handcrafted buildings whose structural integrity improves through earthquakes, witnessed incredible wooden and stone detailing, took in shrines, temples and gardens with ritual and tradition woven into their architecture, and meandered through streets born not of a grand planning scheme but through the organic growth of an ancient city. Places that had care and purpose in all aspects of their being. It was this same care and thought that we expected to see in the reconstruction of the site at Hashikami and in the surrounding Tohoku region. What we found, however, was a design approach devoid of consideration for the places in which it was meant to provide a solution.

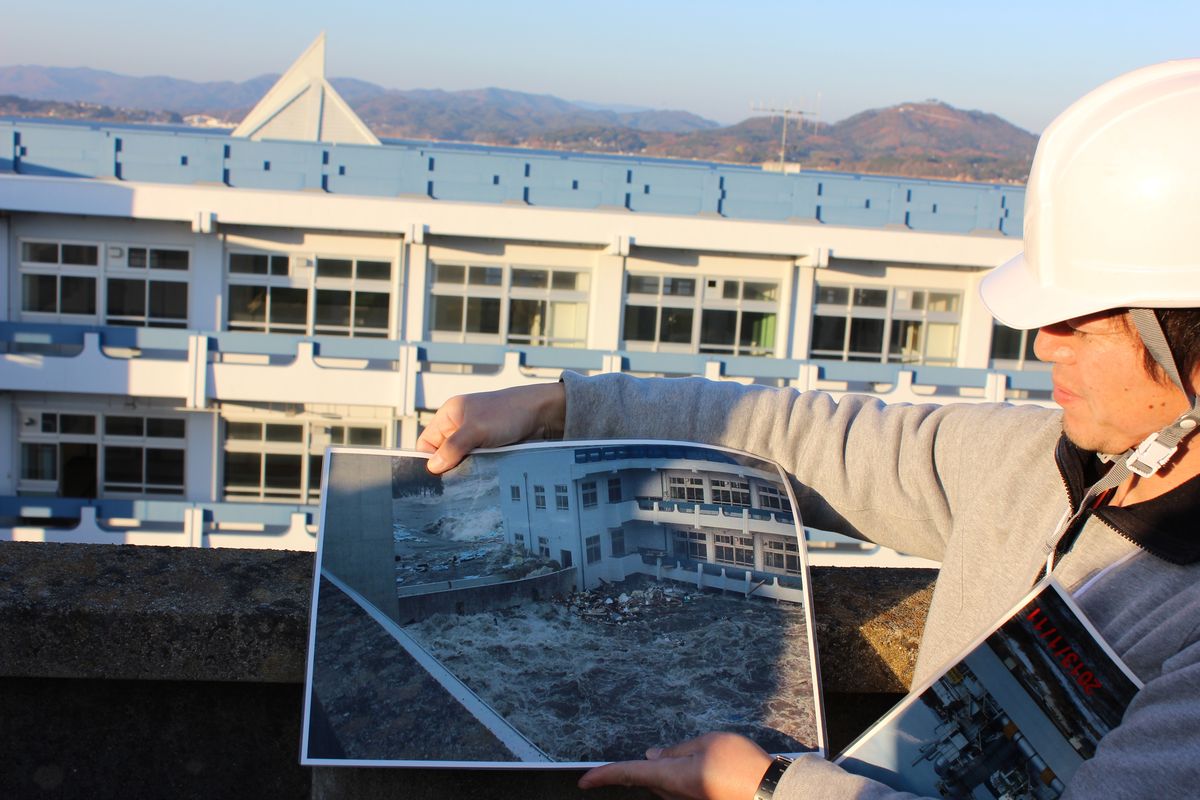

The Japanese government has implemented two policies in response to the Great East Japan earthquake; one of group relocation – moving residents to temporary housing on higher ground; and one of disaster prevention – building concrete seawalls and breakwaters along the coast. There are significant issues with both these approaches, and both have been met with resistance from local landowners and communities who have been unable to return to their homes to work and rebuild as their land is currently being used to house vast amounts of soil and machinery for the seawall project. The government’s policy seeks to secure the Japanese coast prior to any community reconstruction, which now five years after the disaster, has had huge implications for the social, economic and environmental sustainability of many traditional fishing villages along the coast.

The seawall response has created the illusion of recovery, an elaborate parlour trick hiding the underlying problem of a country whose urbanization has now expanded to low-lying areas, displacing the generations of knowledge and stories embedded in the landscape. However, instead of learning from the planning mistakes of the past fifty years, the government has offered a one-size-fits-all approach to the problem, not of how to better design and work with natural disasters, but rather how we can “protect” against them through engineered solutions. This illusion of protection and lack of connection to place became utterly apparent at Rikuzentakata, where we were lucky enough to talk to one of the engineers behind the seawall project and even have a tour of the wall itself. From on top of the wall, the devastation left by the tsunami is still clearly visible. We learned of plans to reestablish a local pine forest and construct a tourist walk around the seawall, alongside land-raising with soil taken from the surrounding mountains. This so-called solution – bringing commerce and people back to Rikuzentakata – will essentially isolate the town from the very part of the landscape that brought people to live there in the first place: the sea.

The seawall at Hashikami National Park.

Image: Hayden Matthys

Hashikami, the town we were working in, had a slightly different story to that of Rikuzentakata. Here the seawall and land-raising project had been slowed, if not halted, by community outcry in favour of a solution that would work with the residents to build a future in which they could once again live in harmony with the ocean and protect their identity of place. We were invited to share our own design ideas at a workshop with the Hashikami community, as a way of offering new perspectives on the reconstruction of their town. Through this we were privileged to hear many incredibly moving stories from people who had lost so much, and for the first time it truly felt that we were part of something far more important than ourselves – that we were dealing with people’s lives and livelihoods and that what we designed could truly make a difference.