Between 1947 and 1978 the public works department of the city of Amsterdam built over seven hundred playgrounds, most of them to the designs of Aldo Van Eyck. The playgrounds took over bombed-out empty lots, junkyards, traffic islands and the oversized pedestrian throughways of new developments. They comprised of a small family of elements arranged with a De Stijl minimalism over mostly flat and hard-paved terrain: an arch of climbing bars, a sandpit, six concrete cylinders of varying heights, a balustrade rail for swinging on. Images of the playground sites before and after are striking – where once was emptiness, now is life. Van Eyck had very clear ideas about the urbanizing effect of playgrounds, which fed directly into and from his broader ideas about planning and the city. In simple terms, these were about the importance of place as opposed to space, and of the “in between”. Both terms are now ubiquitous to architecture, but they were coined by him.

Pirrama Park, at the end of Harris Street in Pyrmont, is the latest in a suite of excellent public spaces commissioned by the City of Sydney. Other recent projects in the ensemble are Beare Park in Elizabeth Bay, Redfern Park and oval, and Reservoir Park in Paddington. All have been transformative. The City of Sydney should be awarded the Institute’s Gold Medal for this energetic promotion of quality urban design. Pirrama is the work of Aspect Studios Landscape Architecture as lead consultants, with Hill Thalis Architecture and Urban Projects and CAB Consulting. According to both Aspect and Hill Thalis it was a seamless collaboration, and the results speak of this.

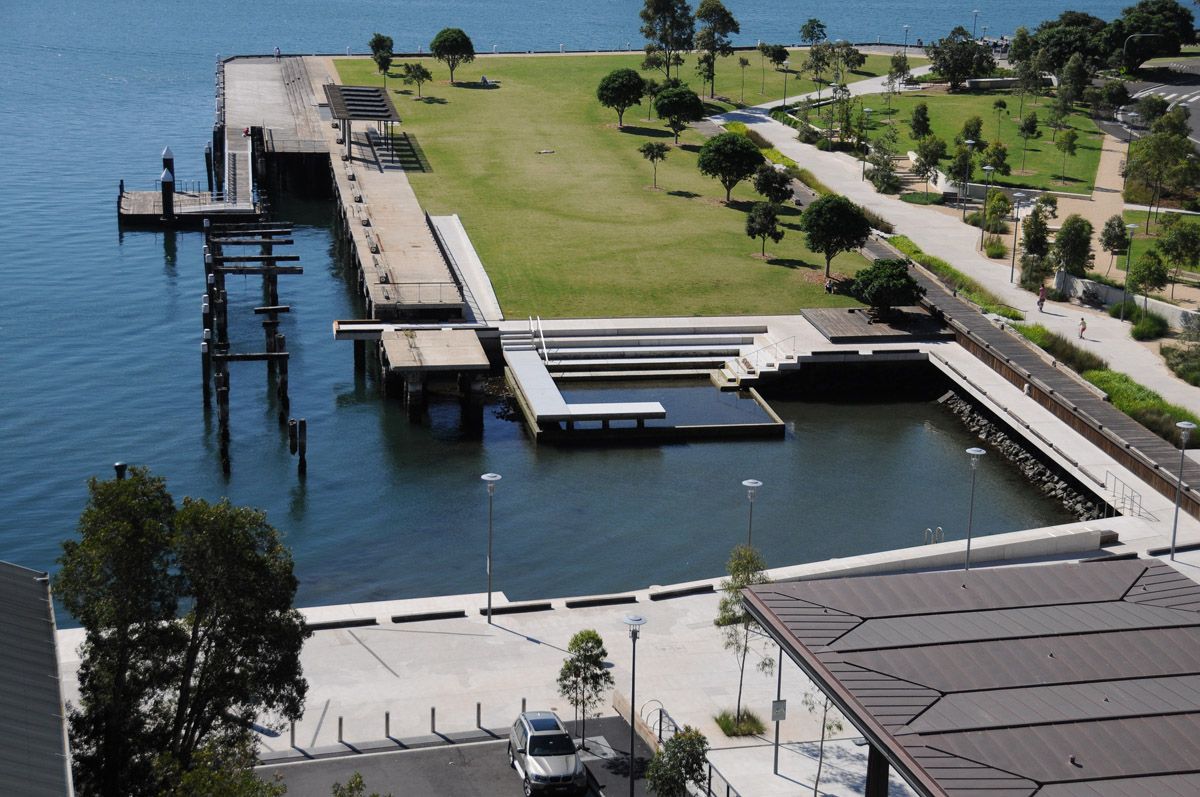

Like all once-industrial waterfront sites across Sydney, the former Water Police site was contested for decades before the city was able to purchase it for parkland. The design process, which started in 2004, involved extensive community consultation and went through several development applications before approval. Though it had once contained many buildings, the site Aspect and Hill Thalis inherited was essentially both flat and flattened. The terrain was part ground, part fill and part concrete pier, with a road running between this flat terrain and the sharply cut sandstone headland that would once have formed its more topographic profile.

Waterfront edges.

Image: Florian Groehn

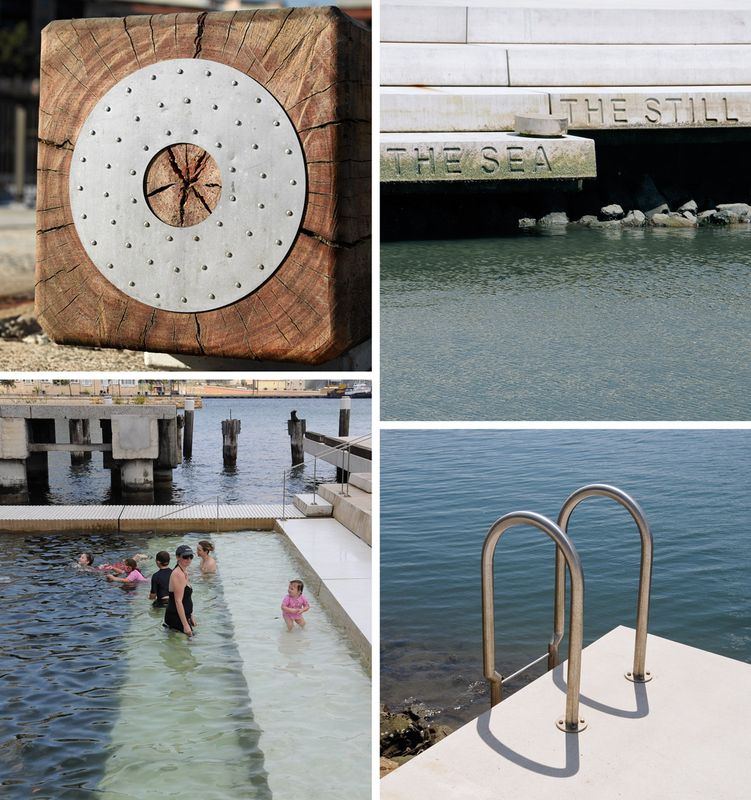

A study of early maps indicated that Harris Street had once ended in a sandy beach with intertidal rock shelves continuing either side. The project references the once-beach by bringing the water back to the end of Harris Street, allowing it “to dip its toes into the water once again”, as Philip Thalis puts it. This is the first in a series of careful moves that animate a very shallow sectional ground plane with great life. Broadly the park is divided into four zones running north-south. The Grove runs along Pirrama Road, creating a slightly elevated edge treed with angophoras. This area steps loosely down to the first of two boulevards – one hard paved, the other raised and decked – which connect across a lush bioretention swale and what was once the concrete dock wall. The Green follows, a grassy plane planted with clumps of Port Jackson figs. The Green links to the Water’s Edge, formed from the existing concrete platform. In some places this is left as is, and in others carved and sliced away to reveal its structure and material make-up. Across this geometry are laid other elements: a wonderful playground formed largely from sandstone elements salvaged from the old Pyrmont Bridge; a more formal square at the end of Harris Street which includes the only building in the park, the belvedere; and the Sheltered Bay, where the old concrete platform and adjacent reclaimed land have been pulled away to create a stepped edge to the water. On the winter days I visit, the harbour is crystal clear and I can well imagine people paddling and swimming here in the summer.

Across the project the material palette is coherent and strong: of concrete overlaid with steel, embellished with timber, much of this recycled from the site. Within this is a dialogue of concrete – off form and precast, off white and standard cement, grit blasted and set smooth. Similarly the project’s environmental credentials are impeccable, with the park now collecting all the runoff from the surrounding catchment, filtering it through bioretention swales and storing it in a vast tank at the northern end for use on both Pirrama and the neighbouring Pyrmont Point Park.

The belvedere uses the steep edge of Harris Street to provide an upper level covered viewing “room” and a lower terrace with a cafe and toilets. Viewed from the north, one can read this structure as a ghostly inversion of the old wool store that sits opposite. The pitched trussed roof has been mirrored to form a slatted timber ceiling; the solid walls translated to nothing. This ceiling and the columns are completed by a crisp concrete base. The columns lean in gently and are offset so that they appear to be walking towards the water. Inset copper channels take water from the roof to a tank below ground. The trusses, identical but flip-flopped in response to the column offsets, give the whole form a slight swagger. It is a beautiful structure and well used. On a sunny winter Sunday, the park and cafe terrace are full of people. It is a good example of a non-intensive use commanding a grandly proportioned space.

Wander, as you will, to the far northern end of the park and you will encounter a commanding view. To the west are Glebe Island and White Bay power station, the Anzac Bridge and, below it, tiny and nestled, the old Glebe Island Bridge. To the north and visible across the entire park is White Bay port with its vast sheds and framed structures. To the east is Barangaroo and the Harbour Bridge beyond it. Three bridges and four vast harbour sites, the latter still coloured yellow for “miscellaneous area” on the Sydney street directory. Not for much longer.

Integrated play space.

Image: Florian Groehn

Should parks like Pirrama be the model for these spaces? Pirrama is beautiful and successful, particularly when viewed through the Anglo/Sydney tradition of park as green space, as a form of reconstructed nature. The designers have worked hard to ensure that it is rich in opportunities for exploration and inhabitation, and one of its triumphs is the unfettered access it offers to the water’s edge. But for all this the model has limits.

When Van Eyck started his playgrounds he envisaged them as a kind “entry level” urbanism, accessible to and comprehensible by all – small projects generative of broader urban possibilities. As long as the starting point for public space in Sydney is the saving of land from residential over-development, then the expectations of our open spaces remain constrained and our attitudes toward them fearful. How do we make our public spaces do more?

This is particularly pertinent to harbourside sites in Sydney. The land is impossibly expensive, a fact that acts to preclude innovation. At the same time the harbour is losing its remaining industry and port operations. It runs the very real risk of becoming little more than a lake, bereft of its true maritime nature and the giant scale that once daily animated it. Only through the powerful manipulation of the possibilities of public space can these two forces, which move gravitationally toward each other like light paths in a galaxy, be prevented from coalescing into a grand but empty black hole.

Sydney needs public places. Places animated by true urban life. This is the kind of life that takes place at all hours and is available to all users. It demands not just vibrant public open space but public buildings, public rooms, public architecture. At some places it is dense and dark, at others light and expansive. It is never locked. It holds the potential for complex programming at the scale of the playground, and well beyond it. It requires boldness and bravery, not fear. It should encourage the unexpected and promote the serendipitous. In addition to all this, it must offer some gesture, some acknowledgement of its maritime past, sharpening the experience of Sydney via an urban embrace of its waterfront. If I have one criticism of Pirrama it is that there could be far more built form here, more extreme scale, more options for programmatic diversity over more hours of the day. This is no criticism of the designers who have fought hard for the built form and complexity of the park as it is. But if the remaining shoreline spaces become like this we shall just be chasing pigeons while something vast is lost irrevocably.

Credits

- Project

- Pirrama Park

- Landscape architects

- ASPECT Studios

Australia

- Hydraulic engineer

- Aurecon

Docklands, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Architect

Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects Pty Ltd

Builder Ford Civil Contracting Pty Ltd

Community consultation People for Places and Spaces

Concrete contractor McEwan Concreting

Drainage consultant Aurecon

Environmental engineer Ecological Engineering

Heritage CAB Consulting

Interpretive designer Deuce Design

Irrigation Hydroplan

Lighting Lighting Art and Science

Marine engineer TLB Engineering

Playground consultant Warwick Donnelly Pty Ltd, Fiona Robbé Landscape Architects, ASPECT Studios

Precast concrete Hanson Precast

Project manager City of Sydney

Structural and civil consultant Aurecon

- Site Details

-

Location

Pyrmont,

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

Type Culture / arts

- Client

-

Client name

City of Sydney

Website City of Sydney

Source

Review

Published online: 28 Apr 2016

Words:

Olivia Hyde

Images:

Adrian Boddy,

Aspect Studios,

Brett Boardman,

Fiona Robbé,

Florian Groehn

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2010