The Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden (AALBG) combines the natural arid zone ecosystems of the local area of Port Augusta with constructed garden ecologies from diverse arid zone ecosystems across Australia.1 The garden unfolds through a loose network of curvilinear paths that invite visitors to experience a mosaic of local and regional arid plant communities. Much like the arid lands of this continent, the AALBG deserves to be more widely known and celebrated, as both a pioneering work of arid zone planting design and a remarkable story of community-driven landscape architecture. First conceived of as an idea in 1981, the garden has been sending down roots since its construction in 1989. The year 1996 marked the opening of the garden to the public. While not the first or only arid botanic garden in Australia, it is perhaps the most spectacular.

The garden features a mosaic of mallee trees, including species with bright gum flowers and stunning minniritchi bark.

Image: Scott Hawken

Arid landscapes feature strongly in the Australian imagination, but with our propensity to cling to the coastline, we tend to know precious little about them. Arid ecosystems are under-represented in botanic gardens globally.2 While not supporting the same density of life as tropical regions with their abundant rainfall, arid regions are nonetheless home to a range of remarkable life forms that have evolved to live in such extreme conditions through clever and efficient use of available resources, climate-specific adaptations, and approaches to ecological succession and reproduction that harness the particular environmental dynamics of their areas. The arid and semi-arid regions of Australia encompass some of the nation’s most extensive intact ecosystems, including the Central Ranges, Great Victoria Desert, Great Sandy Desert, Little Sandy Desert, Gibson Desert, Simpson Strzelecki Dunefields, Nullarbor Plain and the Flinders and Gawler Ranges. Conservation of these environments is key to addressing the current biodiversity crisis.3

Remnant chenopod and western myall dune ecosystems are woven together with majestic views in a dramatic and fluid whole.

Image: Scott Hawken

The AALBG began in the imagination of horticulturist John Zwar after he moved to Port Augusta to establish the Parks and Gardens department within the council there in 1975. Zwar grew to love and appreciate the area’s dramatic landscape and dry beauty, and realized the need for a botanical resource for experimentation and knowledge development, and to conserve the ecology of these landscapes and their unique collection of plant communities. His vision was nurtured by a friends group who promoted the vision through conferences, fundraising activities and communications with government and business. As part of this engagement, Western Mining Corporation became involved in the 1980s and began to fund small projects to support the garden vision.

Plans for a proposed garden were drawn up in 1986, in the Arid Lands Botanic Park, Port August: Masterplan and Management Plan report produced by the engineering and project management firm Kinhill Stearns for the South Australian Department of Agriculture. This first proposal, however, was rather theme-park-like, featuring arid landscapes from other parts of the world, and was not in tune with the limited resources and funding available.

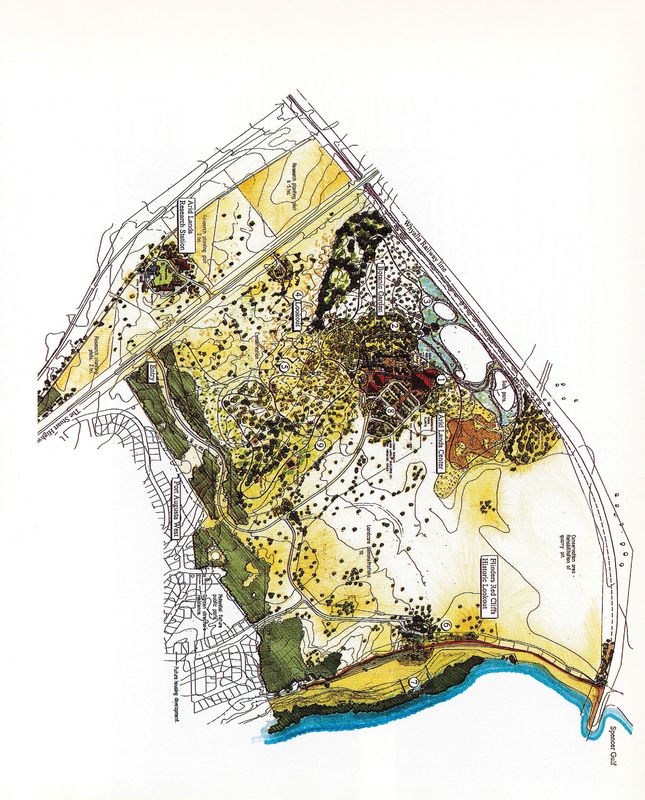

Zwar eventually moved away from Port Augusta to Roxby Downs, some 250 kilometres away, to work with the Western Mining Corporation. A purpose-built mining town north of Port Augusta, Roxby Downs supported the copper and uranium mining operations at nearby Olympic Dam. Zwar’s time here helped consolidate the commitment by Western Mining Corporation to the AALBG. One of the projects funded was a new masterplan by the landscape architect Grant Henderson. Henderson was a recent graduate who had been recommended by his professors, Ken Taylor and Kath Wellman, academics from the University of Canberra. The design development process unfolded over a six-month period that Henderson spent examining the site. The garden as we know it today is close to what Henderson envisioned in his original masterplan, which was completed with the Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden Management Advisory Committee in 1992.4 The report sat on the shelf for some time before the Western Mining Corporation and the friends group managed to motivate the local and state governments to commit funding and the project commenced. Today, the Botanic Garden is financed, owned and run by Port Augusta Council with support from the friends group (now known as the Friends of the Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden).

The region’s characteristic red earth is used as a feature in its own right and appears prominently between plantings.

Image: Scott Hawken

The garden features zones representing distinct regions, including one featuring the plants of the Great Victoria Desert, 900 kilometres to the west.

Image: Nearmap

Henderson’s vision is a sensitive calibration of new gestures with the wider landscape and perhaps the most powerful design strategy deployed is the use of borrowed landscapes. The garden’s paths reach out and weave the various remnant chenopod and western myall dune ecosystems and majestic views together in a dramatic and fluid whole. The vision created by the masterplan reflects an understanding of the site and its surrounds as part of an ancient continent and highlights the drama of nurturing a garden out of a land that is old, fragile, harsh and also immensely beautiful.

The garden as it is today is close to what landscape architect Grant Henderson envisioned in his original 1992 masterplan.

Image: Grant Henderson

To achieve Henderson’s masterplan, the AALBG’s chief and only gardener at the time, Bernie Haase, worked with the friends group to source and grow the plants for the garden. As the necessary arid plants were not generally available, expeditions to remote regions were required to develop the collection. Given that the southern arid lands that the garden features cover roughly one-third of the continent, this was no small feat. Among the first gardens to be created on the site was the eremophila garden, which has since grown to establish itself as one of the most extensive collections of the genus in the world.

As an experimental garden featuring arid species, the planting design on site involved a strong element of unpredictability. The garden’s entry court is an example of this, where an early idea to create sinuous waves of bluebush (Maireana sedifolia) that alternate with a variety of eremophila species was unsuccessful as plantings were spaced too far apart. Those plantings were subsequently replaced and the entrance to the garden today includes spectacular porcupine grass (Triodia scariosa) and desert peas, including regal birdflowers (Crotalaria cunninghamii). Plantings in the entry court focus largely on plants of the Great Victoria Desert. Within the garden, the region’s characteristic red earth is used as a feature in its own right and appears prominently between plantings, unlike many gardens in temperate regions where landscape architects and gardeners seem wedded to the idea of full coverage of the earth by greenery. This sparse quality is distinctive within the garden and is a natural quality of arid regions, reflecting the scarcity of resources in these dry landscapes.

Spectacular porcupine grass (Triodia scariosa), regal green birdflowers (Crotalaria cunninghamii) and other desert peas greet visitors at the entrance to the garden.

Image: Scott Hawken

Looping paths link different botanical collections from various deserts around Australia.

Image: Scott Hawken

Many years prior to the establishment of the garden, much of the landscape would have been cleared of its small trees (including western myall) as a result of over-grazing, the collection of firewood and dumping. A visit to the garden today reveals how a new mosaic of mallee trees, with their startling bright gum flowers – and many with extraordinarily beautiful minniritchi bark – has rejuvenated the landscape, creating a delightful open woodland with dappled, plentiful shade. Such mallee woodlands are characteristic of semi-arid regions and contrast with the low shrublands of more arid landscapes.

Arid landscapes, with their unreliable rainfall patterns, are challenging environments in which to establish a garden. Following rains, Australia’s arid landscapes sporadically blossom as a giant floral display, as seeds and plants take advantage of the limited window of moisture availability. To make arid gardens appealing all year round, a range of irrigation strategies are necessary. As it is for most of South Australia, water for the township of Port Augusta is precious, being transported from the distant Murray River; the town itself receives only a nominal rainfall of 250 millimetres. Intensive seasonal soaking through drip irrigation for periods as long as 48 hours encourages plants in the AALBG to develop deep roots and build resilience to endure these dry spells. In a world where arid landscapes and ecologies are both expanding and under stress, the AALBG is an important resource for experimenting with and testing new plants and their horticultural applications. It is a testament to the idea that it is possible to create a surprising and outstanding garden in the desert, and that cities located in such dry conditions can green their streets and parks by working with unique local ecologies.

The success of the AALBG is a tribute to the long-term commitment and visionary thinking of Zwar, the dedication of the friends group, and the skills of Grant Henderson, who gave form to a community-driven vision that has continued to evolve and grow over time. Many great works of landscape architecture of recent times have had community beginnings. This model is one that should be developed and supported more within the profession. It’s clear that a garden with the support of a community can flourish and endure the longest of droughts.5

Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden is located on the land of the Barngarla people.

1. J. A. McNeely, “Biodiversity in arid regions: Values and perceptions,” Journal of Arid Environments, vol 54 no 1, 2003, 61–70; S. L. Pimm, C. N. Jenkins and B. V. Li, “How to protect half of Earth to ensure it protects sufficient biodiversity,” Science Advances, vol 4 no 8, 2018, science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aat2616; E. O. Wilson, Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life (New York: Liveright, 2017).

2. Botanic Gardens Conservation International, bgci.org (accessed 3 April 2022).

3. J. A. Kerle, M.R. Fleming and J. N. Foulkes, “Managing biodiversity in arid Australia: A landscape view”, in C. Dickman, D. Lunney and S. Burgin (eds), Animals of Arid Australia: Out on their own, or hung out to dry? (Mosman: Royal Zoological Society of NSW, 2007), 42–64; S. L. Pimm, C. N. Jenkins and B. V. Li, “How to protect half of Earth to ensure it protects sufficient biodiversity,” Science Advances, vol 4 no 8, 2018, science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aat2616; E. O. Wilson, Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life (New York: Liveright, 2017).

4. Grant Henderson and Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden Management Advisory Committee, Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden, Masterplan Extensions and Recommended Modifications: Report to the Management Advisory Committee Port Augusta, June 1992, Canberra, 1992.

5. The author would like to thank Port Augusta Council, Chris Nadya and John Zwar and the Friends of the Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden for their hospitality and assistance in providing information for this article.

Source

Review

Published online: 24 Nov 2022

Words:

Scott Hawken

Images:

Grant Henderson,

Nearmap,

Scott Hawken

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2022