The view that urban planning, policy and design should be a neutral framework has not led to greater inclusion and safety in public spaces. Indeed, through the misuse and misinterpretation of neutral approaches, practitioners – even if unintentionally – can negatively impact the ability of communities to participate safely in public life.

While neutrality may be useful for undoing harmful and limiting gender stereotypes (like, for example, the gender stereotypes that shape children and teens via play, fashion and media), the misdirected belief that the design process can “objectively” guide solutions and resist bias ignores the everyday experience of minoritized people. In fact, in the disciplinary context of urban design and architecture, “neutral design” is rarely – if ever – neutral and results in practitioners failing to engage ethically with the social issues faced by minoritized people.

Conceived by US scholar and civil rights advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality describes how discrimination is more complex than a singular axis of oppression. Social identities in an intersectional framework include but are not limited to Indigenous identity, ethnicity, race, sex, sexuality, gender identity, parent or carer status, disability, mental health, religion, migrant and/or refugee status and experience, age, socio-economic status and background, cultural background, and educational and community background. Many intersectional criteria change over time, which means that identity, needs and priorities will likely change across a person’s lifetime. In the context of urban life, intersectionality shapes the rights of people in communities and can exclude minoritized people from safely accessing public amenity, thereby limiting their sense of belonging and ownership of public spaces.

Most design practitioners understand the responsibility to ensure the positive, long-term impact of their projects and have committed to understanding diverse stakeholder perspectives. Noting their own lack of expertise they have become more conscious of methodologies that ethically engage with the values or “lived experience” of the communities they are working alongside. They increasingly recognize the need to reject “neutral” frameworks, acknowledging that neutral design is far from inclusive and safe, and more likely reductive and exclusionary.

Addressing neutrality – and taking up an inclusive, intersectional approach to design –requires disestablishing hierarchies. Inclusive and intersectional design recognizes possible points of exclusion, such as perceptions of personal safety, and feelings of risk and vulnerability when navigating public spaces. Inclusive design recognizes that to create cities that are sensitive to intersectional experiences, practitioners need to engage with the breadth of perspectives in the communities that will presumably benefit from the projects they are engaged to undertake.

Ideally, legislation should be in place to demand the equitable distribution of civic resources (and the processes to support this). But, with or without legislation, specific approaches to public space design can authorize designers to challenge the fixed attitudes associated with entrenched and outdated “neutral” urban design principles. These include redressing “gender-neutral design” (essentially “default male”) and ensuring that crime prevention is critically implemented with evidence-based approaches to ensure that it does not further disadvantage women and minoritized people.

The first action in an intersectional design process is to identify and engage with local organizations and community groups, especially local Indigenous groups, whose perspectives will need to be sought and respected throughout the project. The establishment of an advisory committee will provide guidance, specialization and input from disciplinary experts. Generally, the committee is constituted to reflect the community and its role is to support the project team to focus on the needs of diverse communities and to provide a critical intersectional lens. The equal representation of community groups, stakeholders, community leaders, local government, researchers, peak women’s organizations and local activists is paramount. The committee should be intergenerational, prioritizing people who may be traditionally excluded from the design consultation process – for example, ethnically minoritized women, lower socio-economic groups, disabled communities and/or people who are gender-diverse. The design team and client representatives should be sensitively embedded in the advisory committee to ensure that their insights provide context and currency to all stages of the design process.

The committee can facilitate introductions to key organizations who will benefit from the project and who can provide additional input into the project design and execution. For example, the implementation of an intersectional safety audit will require convening small groups from the local community (particularly local women and minoritized people) to gather first-hand experiences of the site and context. This will assemble community perspectives on the critical social issues that might otherwise be missed by practitioners or those who see themselves as public space “experts.” The process will illuminate the effectiveness of existing urban design principles such as lighting, maintenance, surveillance, sightlines, visibility, wayfinding and egress. Intersectional safety audits garner insights about the perceived efficacy of existing crime prevention interventions by inviting members of the community to identify the factors that make them feel unsafe or safe. Participants may also offer ways to improve spaces from a local community perspective that is likely to be highly valuable to the design team.

Deploying an intersectional budget will prioritize the equitable allocation of resources, such as the provision of public services and appropriate social and recreational programs as well as the necessary facilities and infrastructure. A key expectation for public space projects should be that the design budget addresses the specifics of intersectional experience within communities – designing with, for example, the specificities of ethnicity, age and socio-economic status. This will ensure that diverse communities can access public spaces safely and that the outcomes can be measured in terms of impact.

The effective allocation of resources is intrinsically linked to the availability of quality data. The abstraction of incomplete data is commonplace and can be used by practitioners to justify decisions that may negatively impact communities. While census data, crime statistics and community survey data (as well as data from mobile phones, social media, news media, mobility data, financial data and satellite data) can be useful, these sources may not accurately reflect the experiences of the minoritized people who should benefit from public space amenity. Generating or commissioning qualitative and quantitative data for projects will ensure the data reflect the local community and can then be ethically triangulated for interpretation and application.

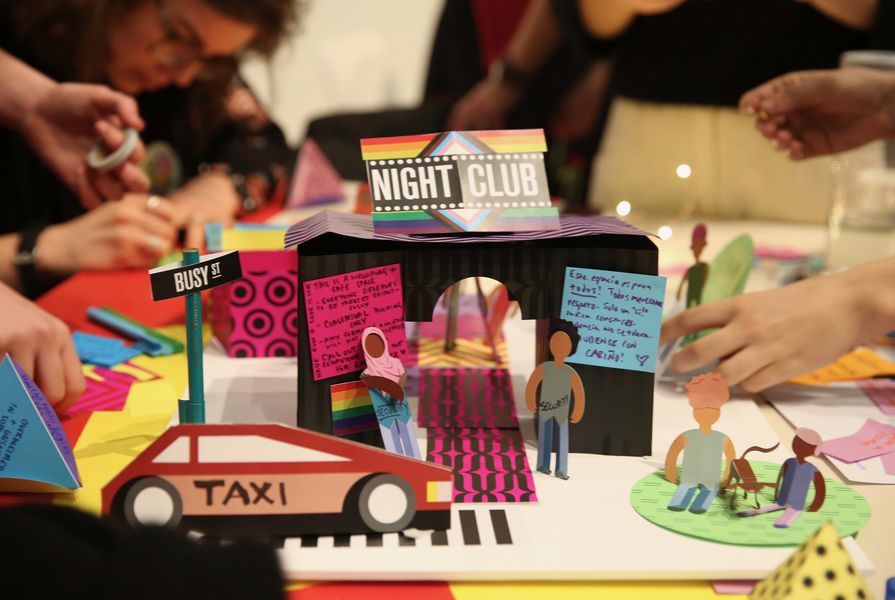

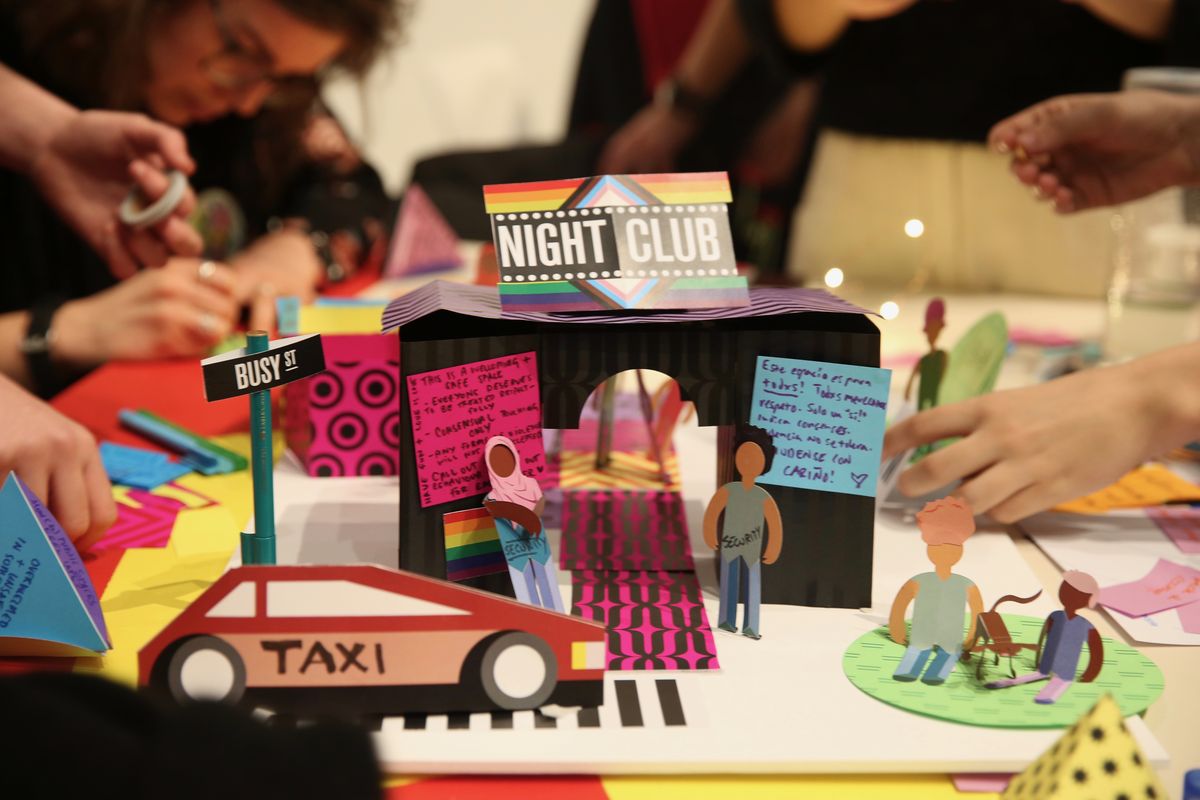

The involvement of communities in the design process is a key indicator of an organization’s commitment to implementing inclusive public spaces. A co-design methodology , which actively encourages the sharing of power in the design process, will ensure that minoritized groups are understood as credible, expert contributors to the development of public spaces and will address the community’s key concerns. Co-design currently suffers from being a buzzword around which design practices adopt ad hoc approaches. Expert facilitation of the co-design process is critical, along with a keen understanding of intersectionality and power dynamics to drive successful participatory engagement.

Practitioners should not underestimate the need to invest in both understanding and actioning intersectional principles for public space design. Participatory approaches will ensure that communities are empowered to contribute knowledge about their experiences and feel that their rights, needs and desires in public spaces are met. This co-production of public space reconfigures the role of practitioner as “expert,” recognizing the value of lived experience to the design process, and argues that minoritized people – those who should benefit most from public spaces – should be a part of defining the problem and proposing the solution.

Source

Practice

Published online: 15 Mar 2023

Words:

Nicole Kalms

Images:

Courtesy of XYX Lab

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2023