Image: John Gollings

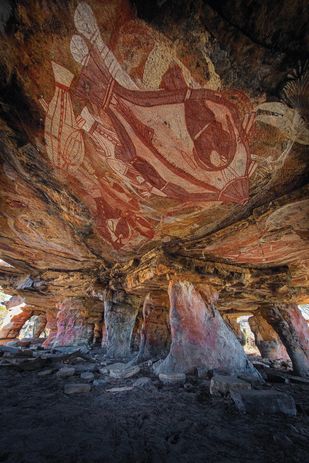

Early on the morning of 7 July 2006, at the height of the northern Australian dry season, helicopter pilot Chris Morgan and former cultural and environment manager of the Jawoyn Association Ray Whear were on a routine aerial survey of the western Arnhem Land plateau for the Jawoyn people in the Northern Territory’s Top End when they flew across a dark shadow along a long quartzite outcrop just east of the border with Kakadu National Park. They turned the helicopter around and landed nearby to investigate, walking into an incredible art gallery under a horizontal rock roof perched two metres above the surrounding plains. Unlike the more familiar rock-shelters that litter Arnhem Land’s “stone country,” this cathedral-like edifice had its roof held aloft by dozens of vertical rock pillars. How did the site, presumably a geological feature in which people once lived and painted, come about and how are we to think of such a rock structure richly decorated with Aboriginal works of art?

Whear immediately reported the site to the Aboriginal community for whom he worked and notified Margaret Katherine, a senior Elder of the Buyhmi clan and traditional owner of the area that houses the site. Within a few weeks, Whear and Morgan flew to the remote western Arnhem Land community of Kabulwarnamo to report the finding to highly regarded artist and culture man the late Bardayal Nadjamerrek (“Lofty”), also respectfully known as Wamud Namok. They flew him to the site, where he recalled having camped as a young boy with his father back in the 1930s, as they traversed the plateau on foot from the north to Jawoyn Country in the south. Both then and now, the floor of the site was littered with slabs of quartzite rock, each some forty centimetres long by twenty centimetres wide and ten centimetres thick. Those rocks had originally come from the ceiling and had been shaped by flaking the edges; they were “pillows” that the old people had put there to rest upon, remembered Lofty. The old people had called this place Nawarla Gabarnmang, he said, meaning “hole” or more precisely “cleft in the rock.”

Image: John Gollings

It would be easy to think of Nawarla Gabarnmang as a natural double-ended cave where people lived, a geological stage on which cultural activities took place. But there is another, more appropriate way to approach the site.

Let us begin by stepping back deep in geological time. Some 1,700 million years ago, sands were laid down in what was then a shallow marine environment. The sand became deeply buried in accumulated sediments and over time the seas receded. Over millions of years, strong forces of compaction bound the sand particles and surrounding finer sediments together, forming sandstone and in due course harder quartzites. But the weight of the thick rock mantle created hairline fractures through which water slowly ate away at the rock. Along those fissure lines, still buried underground below the water table, the soft, weathered sediments grew as the millions of years unfolded. Eventually the rock rose above ground, allowing flowing water to slowly wash away the weathered quartzite that had turned back to sandstone and then to sand. Vertical cavities were left behind where the fissure lines once ran, separated by the remnant rock that now featured as pillars. The largely untouched ceiling is made up of the exposed rock layers that lay above the once-buried weathered horizon.

Image: John Gollings

Originally the rock pillars were not widely spaced. They were typically about one metre apart. We know this because this is how they are found in other parts of the site that people did not frequent. We can also see where missing pillars once stood, for their very tops remain adhered to the ceiling and their bases have survived on the floor in those parts of the site where the pillars are now more widely spaced. In some areas, pillars are now eight metres apart where once they stood side by side.

This is where Nawarla Gabarnmang’s story takes an unexpected turn, causing archaeologists to rethink how we have come to view caves and rock-shelters, along with the broader landscapes in which they sit.

Image: John Gollings

Fifty thousand years ago, Aboriginal people started to camp at the site, first at the edge and then gradually further within. Living amid the pillars was not possible at first, for they were too closely spaced. But sometime between 35,000 and 23,000 years ago – the exact timing is uncertain as more research is required – individual pillars began to be toppled. This required planned, structured dismantling, for the weight of the roof would not allow the rock pillars to be simply pushed aside. First, the pillars’ top layer was flaked away or, in some cases, vertically sectioned and removed as a block, all with stone tools, creating a space between pillar and ceiling. That space then allowed the pillars to be pushed aside and dismantled piece by piece. The overlying ceiling now lacked local support, so individual layers of ceiling rock began to collapse. Where pillars had gone, the ceiling level was now higher than in surrounding areas. The individual toppled pillar fragments and ceiling slabs were flaked into typically forty-centimetre-long pieces and carried away to the shelter’s outer edges, so that today hundreds if not thousands of regularly shaped tabular blocks abound at the rock-shelter’s northern and southern entrances. A few of those tabular pieces were left on the shelter floor and moved around. They each show signs of use, sometimes from the grinding of ochre to make paints in shades of white, red, pink, yellow and black. Others were used as anvils to rest higher-quality stone for the flaking of stone tools. It is these tabular pieces remaining on the shelter floor that local Aboriginal Elders refer to as “pillows,” demarcating where in the past people rested. The extant pillar walls and ceiling rock surfaces are heavily decorated with paintings, so much so that in some places more than thirty layers of paint have been identified, motif over motif in a time sequence that represents centuries of changing styles. And how are we to think of the accumulated slabs at the shelter’s northern and southern entrances: rejected debris to clear the site or a cache of useable tools and furniture? In some cases, slabs were overlaid in multiple tiers to make stools for artists to stand on when painting the ceiling.

Image: John Gollings

About 11,000 years ago the toppling of pillars ceased. We know this through the archaeological excavations that revealed parts of collapsed and dismantled pillars. Carbon dates on charcoal near the buried pillar fragments enabled us to date individual events, relating both to the shaping of the site and to the making of artworks. Sometimes paint drops had fallen from the ceiling as wet paint was applied to the rock, those paint drops having dried on the old, sandy ground surface that was then covered with accumulating windblown sediments and ash and charcoal from nearby fireplaces. That charcoal again enabled us to carbon date the painting events now marked underground by the drops of paint that fell as the artists plied their trade.

Nawarla Gabarnmang is a spectacular site, one of the world’s great archaeological rock-shelters. Yet it is more than this. The stone workings – the systematic dismantling of the pillars, the removal of blocks to create more open spaces, their strategic disposal at both site entrances and the decoration of the remaining pillar walls and ceiling – all speak not of a natural cave but of an engineered and furnished architectural space. People engaged with the site as a built landscape. Nawarla Gabarnmang has been culturally designed and redesigned through some two thousand generations of social and cultural engagement with both the rock matrix and the spaces in between; people shaped the rock as they lived and engaged with it. Only here it concerns a deep rock-shelter, a structure that has traditionally been thought of more as a natural feature of the environment than as culturally built. We don’t tend to think of such Indigenous landscapes as engineered or architectural or even as furnished. Nawarla Gabarnmang challenges us to rethink these supposed natural dimensions of the lived world.

Source

Practice

Published online: 25 Sep 2018

Words:

Bruno David,

Jean-Jacques Delannoy,

Margaret Katherine,

Ray Whear,

Jean-Michel Geneste

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2018