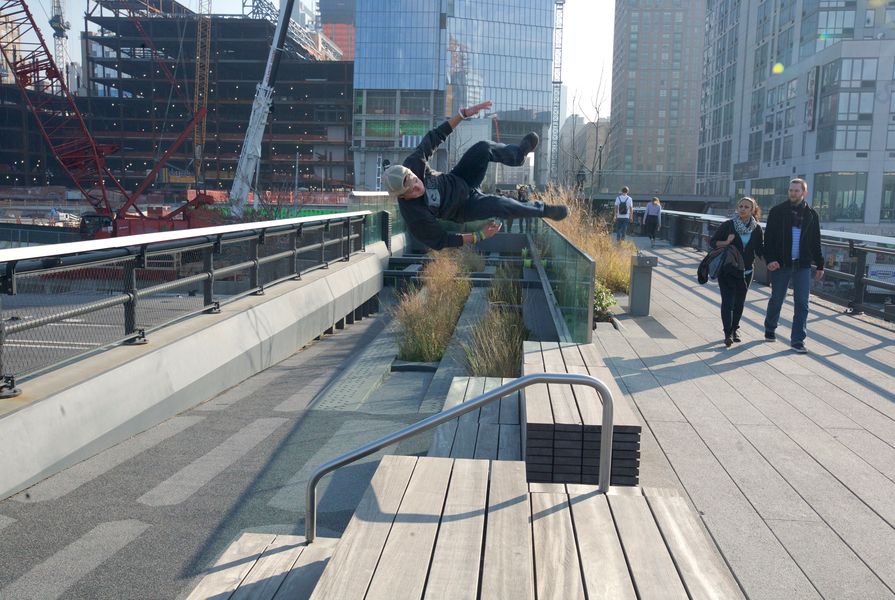

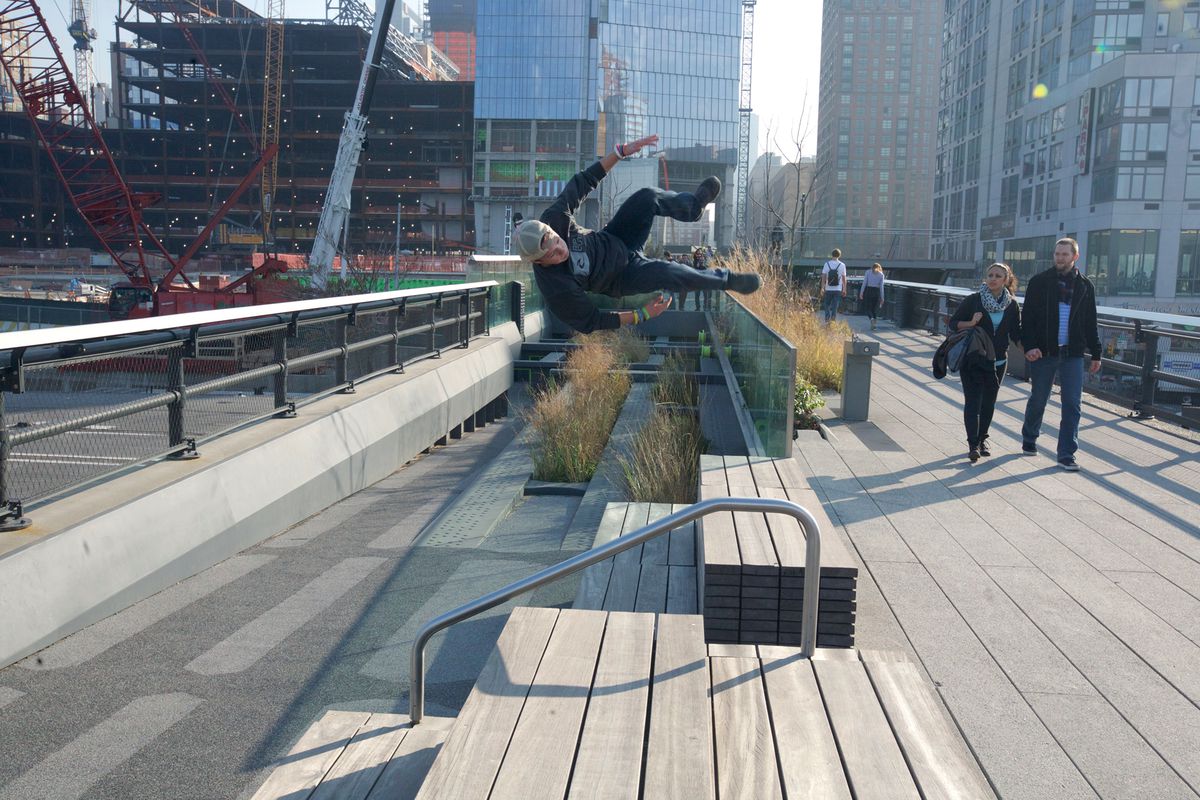

The High Line linear park in Manhattan is arguably one of the most famous pieces of landscape architecture in recent years. It is revered by professionals and tourists alike as a place that provides a respite from the busy city below. When I was visiting New York City in early winter, I found that the High Line lived up to its reputation as a place to visit and a place to linger in, smack-bang in the middle of Metropolis. The High Line’s success comes down to the well thought-out planting design, the re-imagined post-industrial landscape and the ways in which the designers have created a variety of open, shared and intimate spaces.

Betula populafolia.

Image: Annwyn Tobin

The park is owned by the City of New York and yet 98 per cent of its annual operating costs are provided by the Friends of the High Line, according to Robert Hammond, co-founder and executive director of the High Line. Hammond, along with Joshua David, fought for years to save the High Line and led the movement to prevent its demolition, leading to the creation of the park in 2009.

The visitor takes a 2.3km journey along the elevated former goods-line railway in the Lower West Side of Manhattan. It is a journey through a variety of planted zones, pathways and viewing points. Planting designer Piet Oudolf has created an ethereal landscape set into the highly structural concrete pathways that meld with the steel of the railway tracks. The planting echoes the post-industrial landscape of wild meadow plants that took hold over the many years in which the High Line was left disused and neglected.

The planting is impressive with various species flowering and swathes of burnished grasses framing the deciduous trees. There are approximately 400 plant species on the High Line. It is a planting scheme that is intended to be interesting throughout the four seasons. Even during winter in New York, it was a beautiful meadow landscape that drew the crowds and encouraged them to walk through with wonder and linger in various seating areas along the way.

There’s Sesleria autumnalis and Spodiopogan sibiricus; Symphyotrichum laevis ‘Bluebird’ stands out amongst the burnished tones of the meadow grasses. Betula populafolia trees are interspersed amongst the railway tracks. Ilex verticallata ‘Red Sprite’ is a crucial food source for birds that frequent the High Line in winter. The planting scheme is described by the landscape architects as ‘sculptural winter brush’ (The High Line).

Ilex verticallata ‘Red Sprite’.

Image: Annwyn Tobin

As I walked along, there was a thriving lawn space, a fernery and wild brush meadows. There is evidence of how the railway tracks once entered the buildings to deliver goods. These dead-end pathways reference the industrial past and act as viewing platforms out to the streets below. Public art is scattered along the High Line, placed into the gardens and sometimes quite hidden by the planting.

Unsurprisingly, a great deal of new residential development has taken place adjacent to the High Line and new buildings are currently under construction in the blocks nearby as well. The High Line is not just a place to visit, it also provides an appealing view for local residents. The concrete pathways and bespoke seating designed by Diller, Scofidio and Renfro and James Corner Field Operations are meticulously constructed and maintained.

The High Line is worthy of its reputation as a great piece of landscape architecture. This comes down to its design, its construction, its maintenance and – most importantly – the idea of re-imagining it in the first place.

Source

Review

Published online: 8 Apr 2016

Words:

Annwyn Tobin

Images:

Annwyn Tobin

Issue

Landscape Architecture New Zealand, March 2016