As potential shorthand for biodiversity, the term “wildness” might suggest the sorts of spaces and places where the patterns and processes of species diversity and richness might continue to flourish, unhindered by human interference. However, as Bill McKibben asked us way back in 1989,1 does “nature” really exist and, by extension, are there any “wild” places left? Antarctica’s ice is melting as a result of our runaway increase in global carbon; in our deepest oceans, radioactive signatures and microplastics exist in sea life; and increasing evidence is pointing to the long-term continuous human inhabitation of the Amazon2 – a situation well documented on our own continent, but for an even longer period.

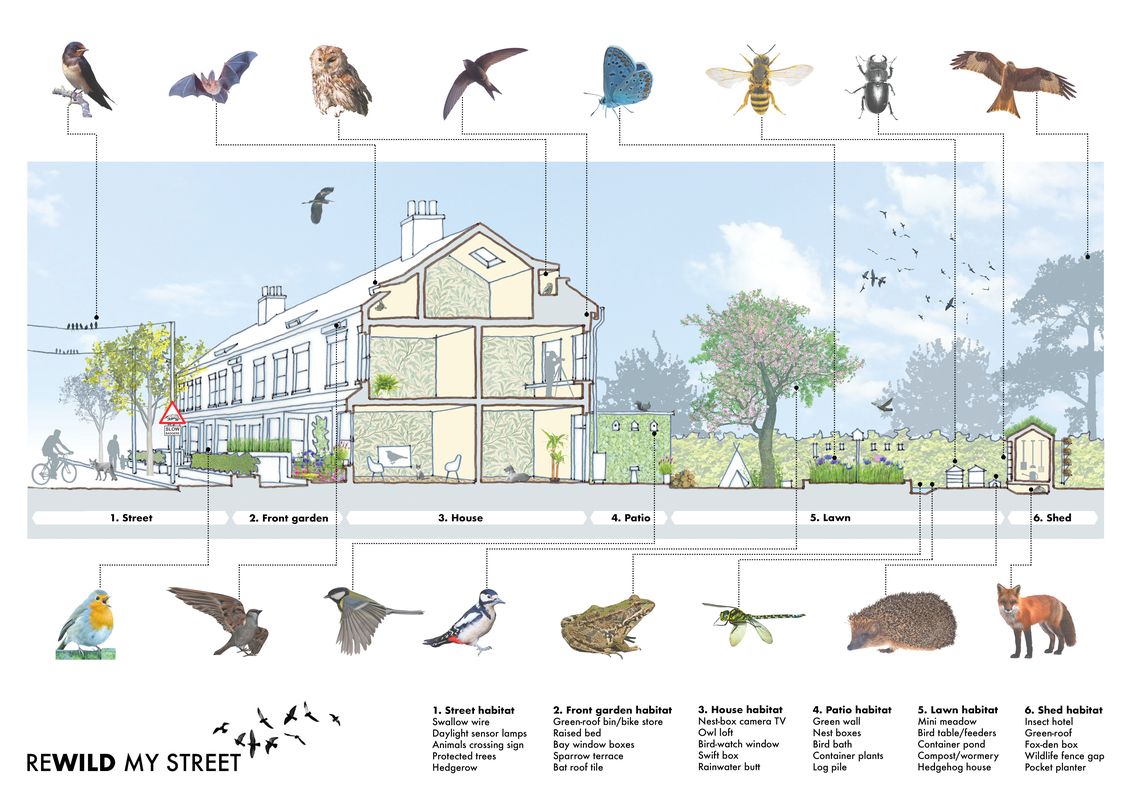

In an urban context, wildness is not a term we often use. Where we do, it is more often a reflection upon behaviour or attitudes – a frame of mind that might lead to a spectrum of boundless behaviour with wild and uncontrollable citizens at one end and more playful, child-based adventures at the other. The term, however, is becoming more common and there is increasing talk of making space for wildness by “rewilding” continents,3 cities,4 streets and rivers. Countries in Europe and, closer to home, Singapore, have embraced this trend with a growing practice of returning culverted rivers into living systems (the River Aire in Switzerland5 and Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park in Singapore), of parks that respect their spontaneous vegetation as the design foundation for wildlife (Park am Gleisdreieck in Berlin) and of respecting the liberty of species to colonize and self-organize (Gilles Clément’s Le jardin en mouvement6). Elsewhere, subtler changes include altering mowing practices and maintenance to encourage greater species in meadows in lieu of turf, and the emergence of engagement work that helps citizens to understand the value of reintegrating the “wild” back into urban environments (the Rewild My Street initiative led by Siân Moxon in London7).

Singapore’s Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park by Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl transformed a concrete drainage channel into a sinuous river that accomodates flux.

Image: Trevor Patt

In Australia, we have so far resisted this approach. On the whole, we continue to efficiently deliver corporate landscape architecture that removes dangers and inconvenience, makes our environments tame and safe and sanitized, and preferences “designerly” gestures over engaging with the underlying unruly tectonic, geological, climatic and ecological forces that persist in our cities. Perhaps this is a response to our more hostile landscapes and their components – places that often already feel wild and boundless, and may be hot, dry or otherwise difficult to access? Or is it because it is only once we have effectively erased wildness (as in Europe) that we miss it and want it to be reinstated?

Our cities in Australia sit upon ground that has, in historical terms, been freshly razed. It is not uncommon – indeed, it is part of our national psyche – for relics of the underlying topography, plants and animals to resurface and remind us of the richness that we have replaced with a thin veneer of urbanity. Think of the “ghost” populations of remnant trees and plants that dot our streets and suburbs, the rock outcrops that have stubbornly resisted erasure or the nightly flocks of fruit bats in our skies. These evidence an as-yet unconquered wildness, reminding us all of where and who we are.

Australia is also the place of the world’s oldest continuous culture. If wildness (and “wilderness”) is often framed as an absence of humans – as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain”8 – then surely this needs some rethinking: the landscapes that we often consider to be “wild” have been managed for many thousands of years.

Konik horses gather at Oostvaardersplassen, a nature reserve and long-term rewilding project in the Netherlands.

Image: E. M. Kintzel, I. Van Stokkum, CC BY 3.0.

Another way to consider wildness in our cities, then, might be to think of it not as a description of place, or as a binary checklist of human/non-human presence/absence, but rather as a continuing series of ecological processes (colonization, change, species flux) and philosophical and ethical framing that is inclusive of the human. Indeed, it is in this latter space that the discipline of landscape architecture is arguably more comfortable and more apt to act. As an industry that tends to outsource the technical aspects of designs on a regular basis, approaching wildness as a process might capitalize on our profession’s key skills in creating lasting experiences of place.

So, why make space for wildness in Australia’s cities?

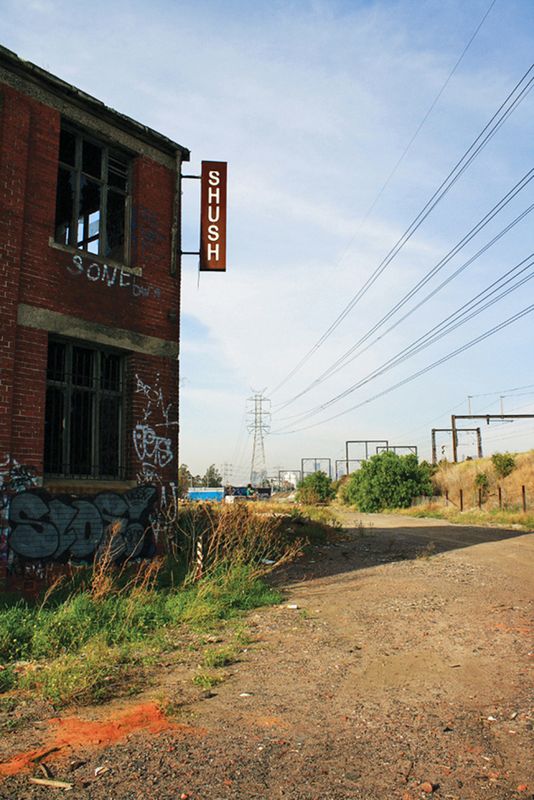

Many of the wildest places lie not in extreme environments or far from cities, but rather closer to home.9 It is in the “terrain vague” of our cities that species recolonize, thrive and diversify, and many of us who grew up in Australia or are avid urban explorers might recall places of mystery, delight and wonder where neglect, decay and abandonment have given rise to a dynamic, rambunctious and surprising mix of plants and animals. Remnant bushland, failed infrastructure or property speculation projects, abandoned land or buildings – anywhere that nature can reassert its systems in the absence of human intervention – are untamed and potentially “wild” places. These places are familiar – they resonate with us, evoke a sense of the passage of time, of latent and potential change, of surprise and delight, and can inspire design approaches that are an alternative to much of our professional dogma and practice that erases ill-determinacy, authorless evolution and spontaneity.

Vegetation colonizes cracks in the pavement of an abandoned car park along Parramatta Road in Sydney.

Image: Trafford Judd

Unoccupied and decaying warehouses in Footscray, Melbourne host a rambunctious mixture of plants and evoke feelings of mystery and adventure.

Image: Vincent Casey

As a profession, the vast majority of us are urban-based and work at the intersection of people and environment, making us key actors in the future of Australia’s cities. It is here that the potential for us to be formative in the “creation” of wildness is apparent – despite the apparent contradiction of this idea.

But are we leading this charge? The business of rewilding Australian cities might be better considered through the frame of novel ecosystems.10 Sometimes referred to as “reconciliation” or “win-win” ecology,11 or even “designer ecosystems,”12 these approaches imply a shift in understanding, question the objectives of traditional ecological restoration as well as the likelihood of achieving it, and embrace new assemblages of species that also include the human.

In a far less wild Europe, a messier and more nature-focused approach to design is often more prevalent than in an Australian or North American context – messy ecosystems may not align with preconceived idea of neatness that many of us have hidden away inside and still seem to preference.13 Here in Australia, and despite gradual change, we continue to favour soft, European landscapes, deciduous trees, flowers that look like the ones in children’s books, and insects and snakes that don’t bite (and certainly couldn’t kill you).

A spontaneous lawn springs up alongside a cycling path in Park am Gleisdreieck, Berlin.

Image: Simon Kilbane

Landscapes are not static, nor will they ever be. Climate change, cultural shifts and global and local forces (including COVID and the use of public space) are overarching forces that can help us to reconsider the way we design our landscapes.

Perhaps, therefore, rewilding is as close to core business for landscape architects as one could imagine. We are able to envisage and guide the reconstruction of past ecologies, but are also skilled in the craft of places that entwine and bind us, and that can elicit specific emotional and physical responses from users, such as immersion in wildness. Such an approach would not fundamentally be about the mechanics of ecological restoration and selecting local provenance species (although considering this is a good idea), but might perhaps edge closer to concepts of nature play: places that engage us, stir us and give us a moment to reflect, wonder, be intrigued, curious or inspired. Rather than masterplans or even frameworks, could our work instead focus on setting in motion an openness to processes that could then self-determine the genetic and physical make-up of a park, street, city or region?

If our cities are to be rewilded – and if we heed our colleagues overseas – then as a profession, we need to actively accommodate indeterminacy, change and flux. Working with these forces can help guide us in the real business of crafting experiences and toward a genuine shift in how we understand our relationship, both as landscape architects and individuals, to the non-human world.

1. Bill McKibben, The End of Nature (New York: Random House, 1989).

2. Carolina Levis et al, “Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on Amazonian forest composition,” Science, 2017, vol 355 no 6328, 3 March 2017, 925–31.

3. Dave Foreman, Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century (Washington: Island Press, 2004).

4. Yun Hye Hwang and Anuj Jain, “Landscape design approaches to enhance human–wildlife interactions in a compact tropical city,” Journal of Urban Ecology, vol 7

no 1, 23 March 2021, doi.org/10.1093/jue/juab007.

5. Atelier Descombes Rampini and Superpositions, “Renaturation of the River Aire,” 2021, landezine.com/renaturation-of-the-river-aire-geneva (accessed 7 December 2021).

6. Gilles Clément, Le jardin en mouvement (Paris: Pandora Editions, 1990).

7. Siân Moxon, Rewild My Street, 2018, rewildmystreet.org (accessed 11 November 2021).

8. United States of America, Wilderness Act 1963, fs.fed.us/psw/cirmount/meetings/ncbotany/Reed1_Wilderness%20Act.pdf (accessed 7 December 2021).

9. Peter Del Tredici, “The flora of the future: Celebrating the botanical diversity of cities,” Places, April 2014, placesjournal.org/article/the-flora-of-the-future (accessed 7 December 2021).

10. Richard J. Hobbs, Eric Higgs and James A. Harris, “Novel ecosystems: Implications for conservation and restoration,” Trends in Ecology and Evolution, November 2009, vol 24 no 11, 599–605, doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.05.012.

11. Michael L. Rosenzweig, “Reconciliation ecology and the future of species diversity,” Oryx, 2 July 2003, vol 37 no 2, 194–205, doi.org/10.1017/S0030605303000371.

12. Emma Marris, Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013).

13. Joan Nassauer, “Messy ecosystems, orderly frames,” Landscape Journal, vol 14 no 2, Fall 1995, 161.

Source

Practice

Published online: 17 Mar 2022

Words:

Simon Kilbane

Images:

E. M. Kintzel, I. Van Stokkum, CC BY 3.0.,

Guilhem Vellut,

Kevin O’Connor.,

Simon Kilbane,

Trafford Judd,

Trevor Patt,

Vincent Casey

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2022