Landscape Architecture and Digital Technologies: Re-conceptualising Design and Making by Jillian Walliss and Heike Rahmann.

The promises presented by digital technologies could be said to have dogged landscape architectural practice for the past five decades, since the then-radical overlay method was developed by Ian McHarg and promoted in his seminal book Design with Nature (1969). Surely the answers to so many challenges would be made much simpler and be so much more convincing if professionals were able to underpin their thinking and propositions with the power of computerized data gathering, mapping, analysis and even synthesis? Practitioners and academics of the period enthusiastically adopted McHarg’s methods, waiting for technology to catch up with his thinking. Some truly heroic planning exercises were carried out over the next decades, applying his methods using the emerging GIS data-banks on natural and social systems that were becoming available globally. A generation of educators was trained in landscape planning in the USA and through them, McHarg’s methods became normalized across the planet, their radical beginnings (among the most influential moments in the profession’s history) forgotten. Then came CAD, which, despite its relative clumsiness as an object-driven system for landscape architecture, became de rigueur for project delivery everywhere.

The impact of digital technologies on the fundamentals of design over the decades, however, always seemed to lag. The technologies seemed too clumsy to actually lead the creative processes that the profession liked to think lay at its very heart – design and creative problem-solving. Early promise just didn’t seem to be fulfilled and as a profession made up largely of small businesses, landscape architects often avoided the investment necessary to make new technologies work for them. Some even questioned whether technology could ever really influence its magic or its mystery. That, of course, was before the last decade, when everything has changed. Not only has technology caught up with us, it could be said that it has overtaken us.

It is this context that makes the book Landscape Architecture and Digital Technologies: Re-conceptualising Design and Making so timely. Not only do the authors address the historical relationship between landscape architects and digital technologies, they also interrogate the current relationship and discuss major developments that are affecting practice. They suggest probable paths for a digital future where these technologies will not only underpin much of what the profession does, they will also transform how practice is conceptualized and what that can be.

Authors Jillian Walliss and Heike Rahmann are from the landscape architecture programs at the University of Melbourne and RMIT University respectively; both are actively engaged with the technical world and use it successfully in their teaching. In Landscape Architecture and Digital Technologies they combine historical narrative about the profession and its engagement with digital technologies through time with discussion and analysis of contemporary cases in practice. This enables the values and challenges presented by those technologies to be explored and conclusions to be drawn about their wider applicability. The book is global in scope, and the featured practices and projects are varied enough to demonstrate the ubiquity of digital technology in relation to other methods common to landscape architectural practice, such as drawing, diagramming, clay modelling and face-to-face contact. It is the ingenuity and flexibility of the practitioners in their selection of method according to the particularities of each project that makes this journey so interesting.

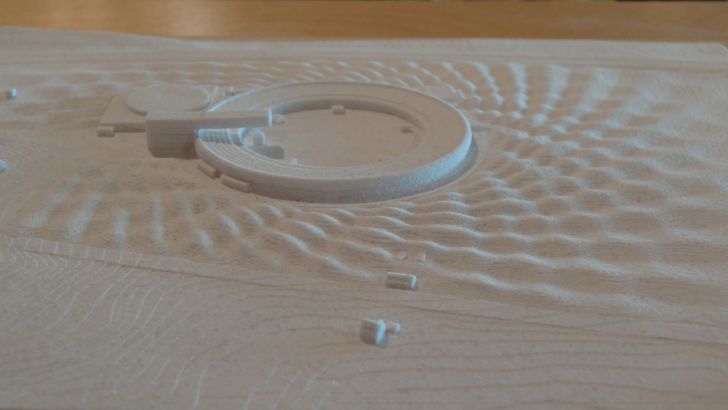

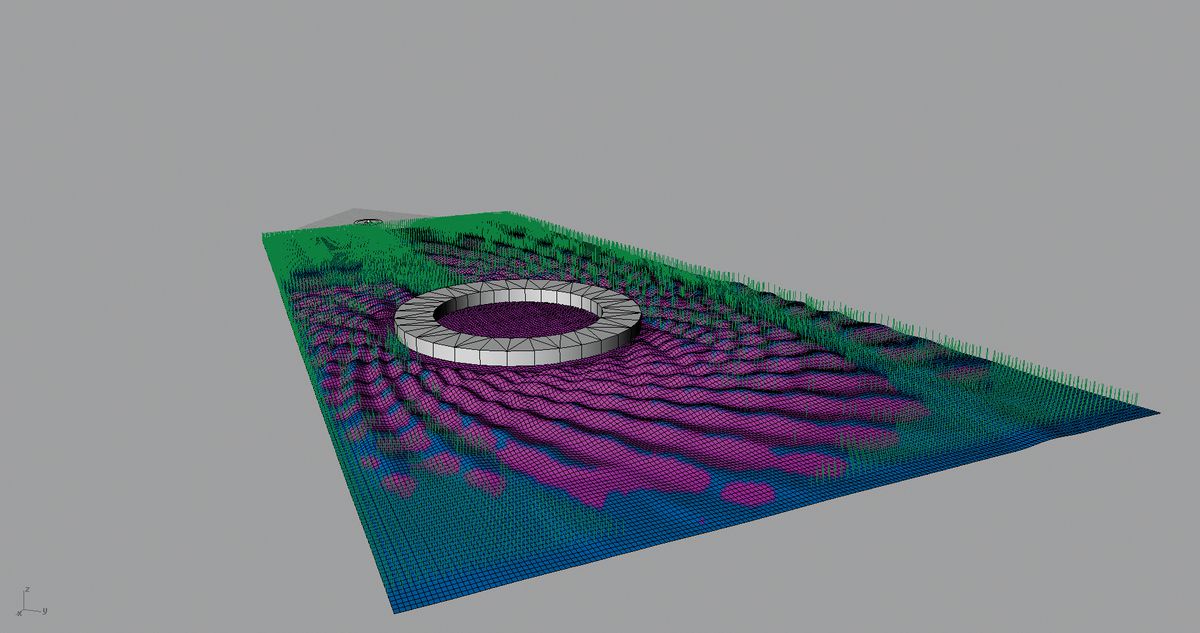

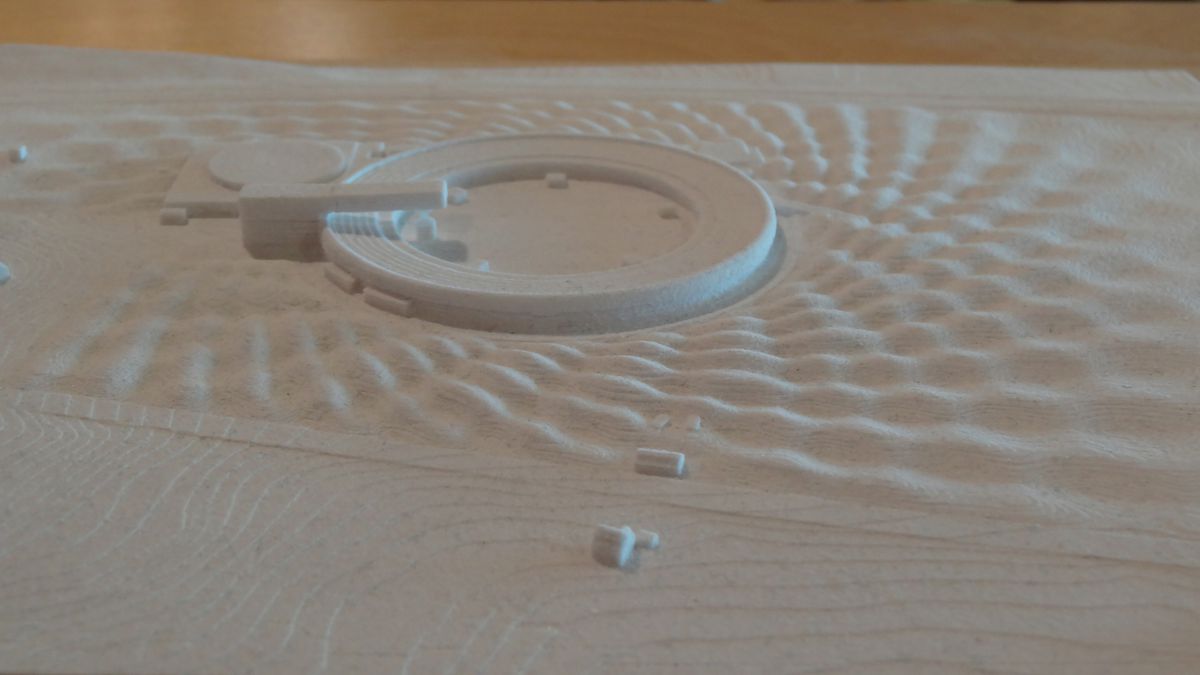

Snøhetta’s unique landscape design for the MAX IV Laboratory in Lund, Sweden, is based on a set of parameters to reduce ground vibrations from nearby highways that affect laboratory research.

Image: Snøhetta

The book is presented in three major sections, the first dealing with recent major advances in topographic modelling and topology. It looks at why these are so powerful for a profession for whom modelling and reorganizing the form of the earth’s surface is fundamental. The second section focuses on recent developments in parametric modelling and its influence on how spatial organization can be conceived within a specifically defined domain, liberated, as the authors say, from and by mathematics. The final section focuses on delivery, as making or fabrication, including a discussion of interrelationships between the many parties engaged in that process and operational effectiveness around data-based parameters (including BIM). The authors use the term “performative” to describe this discussion of a landscape that is active and “does” rather than one that is passive and simply “is.” New ways of thinking about time or the fourth dimension, a preoccupation to us all, are introduced here.

By avoiding concentration on individual commercial computer products, Walliss and Rahmann take a panoptic approach, spreading the discussion across the field and describing how creative professionals now mix and match according to need rather than being slaves, as in the past, to individual products. Designers find the best combination of methods and technologies to underpin their thinking about form, function, experience and production. The authors suggest that in the future, the modus operandi of the effective professional will be, on the one hand, as directors marshalling and selecting from a plethora of design processes; and on the other hand, as editors constantly interrogating and selecting from an ever-increasing array of possible forms, interactions and materials. It is suggested that to be successful in such a future, the experience of the mature thinker (who knows what is relevant) will need to partner with the energy and capacity of the digitally savvy younger generation in new ways. Neither can exist effectively alone.

Rather than being a dry, technical treatise, this book is just the opposite. It reveals how digital technologies now help us understand just what the “black box” of the design process is and empowers us to use that process more effectively to confront the complexities and challenges before us. The authors look beyond the promises of previous decades to lay out the choices ahead. No practice or project is too large, or indeed too small, to avoid being swept along in the current tidal wave of opportunity and variety, or to avoid making decisions about those for itself. Those in the field should read this book and reflect on it.

That being said, perhaps when the next edition is published (and I hope that this book will sell enough globally to warrant that), the graphic design could better manifest and illustrate the content. While the graphic design here is adequate, it far from inspires and is unlikely to expand the book’s market reach. While Routledge is among the most prestigious and therefore credible of academic publishers, it would far better serve the design market it seeks to engage by offering books that are, themselves, expressions of the design they discuss.

Source

Review

Published online: 8 Feb 2017

Words:

Catherin Bull

Images:

ABML4,

Snøhetta

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2017