Kelly Shannon, part of the academic-based research office OSA, based at the University of Leuven, Belgium

Janina Gosseye: You were trained as an architect and have practised in some of the most renowned architectural offices worldwide, including Mitchell Giurgola Architects in New York and Renzo Piano in Genoa. Over the years, however, your focus has shifted away from architecture toward urbanism and landscape architecture. This shift was paralleled by a move into academia. What informed this reorientation of your career?

Kelly Shannon: In today’s urban world, urbanism and landscape architecture are the most effective tools to intervene in the territory and public realm – this is why I engaged with these disciplines.

By the end of the 1980s, when I left the United States having completed my architecture education, the city was merely a playground for private developers, and architects were destined to design envelopes for mediocre real estate. The hallmarks of what Richard Marshall (the Australian urbanist) decades later would label “absent urbanism” were there already: the deliberate construction of city form without coherent morphology and with no attempt to foster a social sphere or public realm. Meanwhile in Europe, strategic projects emerged that involved urbanists and landscape architects from the get-go.

As the European welfare state endeavoured to enhance the interplay of infrastructure, landscape and urbanism, engaged designers coupled with political will created a paradigm shift in the development of the built environment. New strategies emerged where sites themselves – not financing or program – became the controlling instrument of the interface between culture and nature. The reorientation toward urbanism and landscape was thus clear and inevitable for me. In relation to my “shift” into academia, I should note that I continue to champion the involvement of nationally and internationally acclaimed design practices in my research, as I seek to break the more conventional academic modes of design research in architecture schools.

JG: You are an American living in Europe whose work (mainly) focuses on Asia. How do these three contexts compare, and how do they inform your work?

KS: The European welfare state fosters, more than anywhere else, investment in the public realm. Of course, degrees of investment fluctuate with politics, and the current populist wave is worrying. Nonetheless, there have been millennia of political will to create a truly civic society, and urbanism and landscape architecture have thrived in such conditions. For me personally, Europe is the most inspiring environment to live in. At the same time, the scale, speed and scope of development in Asia is mind-boggling. Here, one can immediately recognize that urbanism and landscape architecture can still have a tremendously large and meaningful impact: with landscape serving as a framework indicating where to urbanize and to not urbanize. Furthermore, the determined social engineering in Asian socialist/communist regimes assigns a very different role to the contemporary urbanist. Once they become convinced of projects, they possess significant power to impose structuring elements on vast territories. Their traditions of urbanism have been founded upon an unequivocal belief in planning, which resulted in radical spatial (re)configurations of the territory – spanning centuries from the organized development of irrigation systems to the present-day practice of forming new industrial zones and export processing zones on productive paddy land. Working in Asia allows one to consider the most basic relationships of nature/culture and built/unbuilt.

JG: You are a fan of Canadian author and social activist Naomi Klein’s writing and see a role for urbanism and landscape architecture in addressing climate change. How effective do you think these disciplines can be in addressing this problem if the political support does not exist?

KS: In today’s era of the Anthropocene, humankind is poised as heir to a triumphant age of apparent mastery over nature. Yet, the opposite proves true as strato-spheric ozone depletion, ocean acidification, and more frequent and more severe environmental disasters evince. Jedediah Purdy, an environmental lawyer, has claimed that humanity has outstripped geology, while numerous social and environmental activists and scientists, including Naomi Klein, have argued that the myths of international policy, money and innovative technology as saviours must be debunked. As humanity has transformed, dependence on nature has been progressively minimalized, and we are becoming increasingly aware that consequences can be catastrophic. Surprisingly, urbanism and landscape architecture have largely been absent from this climate change discourse. These disciplines could, however, adopt a central role in defining a new paradigm involving the most fundamental principles of inhabiting the planet through bold regionally scaled projects that address natural, as well as human and political, ecosystems. As climate change is now strongly influencing policy matters worldwide, I am convinced that pressure for such regional plans willmount as leaders seek solutions to shift toward more efficient farming, reducing extraction and developing renewables, increasing forest cover and green in urban areas, and mitigating pollution, the heat island effect and sea level rise.

JG: Of all the projects that you have worked on, whichone are you most fond/proud of and why?

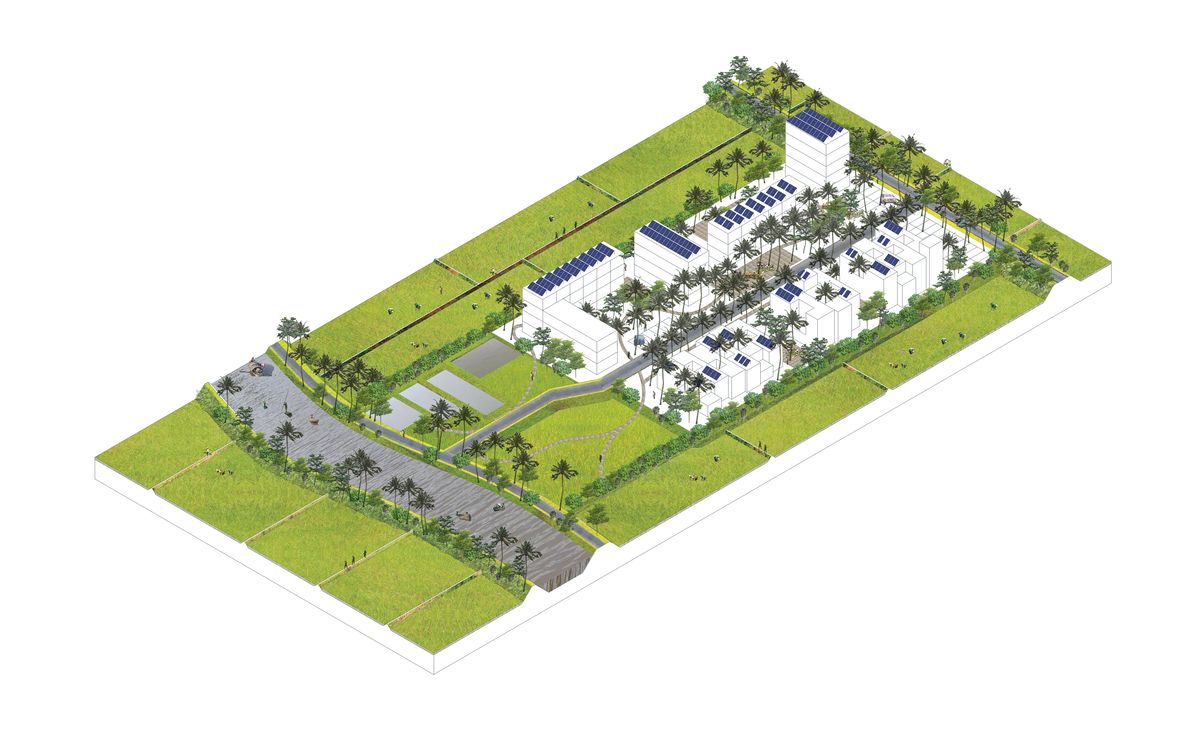

KS: The Mekong Delta Region Plan 2030, Vision to 2050 was a three-year effort where my colleague Bruno De Meulder and I led an international consulting team to work with the Southern Institute of Strategic Planning (SISP) based in Ho Chi Minh City. The plan was recently approved by the Vietnamese prime minister and has been spoken of, together with an earlier plan we also developed with SISP for Can Tho (approved in 2013), as radically conceiving a constructive interplay between unavoidable landscape dynamics and the social, economic and

cultural dynamics of the region. Both plans seized the opportunity of climate change to realign the development of the landscape with the (evolving) geography of the territory. In these Vietnamese projects, landscape becomes infrastructure and resistance becomes resource. They create infrastructures for the twenty-first century that purposefully re-engage with the dynamics of nature and the notion of a thickened deltaic coast; a new and self-renewing ecology that, from the onset, supports a multitude of activities and simple technical interventions that can induce a majestic and varied world.

Source

Practice

Published online: 10 Oct 2018

Words:

Janina Gosseye

Images:

OSA,

OSA/WIT/Latitude

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2018