Landscape Architecture Australia: What are the aspects of domestic garden projects that attract you to this kind of work?

Kate Cullity of Taylor Cullity Lethlean.

Kate Cullity: The home environment and domestic life are fundamental to our lives and they nurture our capacity to relate and perform successfully in our public lives. The overarching goal for the design of residential landscapes is to create home gardens that rejuvenate, relax and enrich daily life. I also like the relationship that is formed with private garden clients – many become good friends.

We find that the domestic garden is a vehicle to explore and test ideas that may later form the basis of designs in larger public projects. Many of the plants we used in the redevelopment of North Terrace in Adelaide, for example, had been tested in my own garden, the Taylor Cullity Garden.

LAA: Are there particular types of domestic garden projects you prefer or avoid (for example, urban, suburban or rural clients)?

KC: Taylor Cullity Lethlean enjoys working on projects where one or more of the following occurs:

• Collaboration with an architect who has designed either a new house or a renovation. It’s rewarding to understand the vision of both the architect and the client and to bring these into focus when designing the garden. Every architect is different so it’s important to remain flexible about ideas and respect what they want to achieve with the building. For example, some architects like the garden to stand back from the building, while others like the garden to encase the house.

• Working with clients who understand the meaning of contemporary garden design, and how ideas can be influenced by the past but not replicated. I avoid clients who want to reproduce an earlier garden style such as a Victorian cottage garden.

• Projects where there is an opportunity to incorporate contemporary art, particularly if we are able to select and commission the artist. Once again, it’s a great opportunity to collaborate to produce a site-specific work.

• Building a narrative into the design. As with our public projects, we like to do this as a way of linking the garden, the site and the client. For example, the gold laser-cut entrance gates at the Adelaide Residence were inspired by my fascination with the world as viewed through a microscope and also I wanted to design an entrance that explored the client’s personality and preferences. The highly glossed gold finish expressed the client’s love of “bling”; the gate pattern is taken directly from an image of a microscopic cross-section of human liver cells (a reference to the client’s propensity for liver-cleansing diets). The gates provide a tongue-in-cheek take on being “cleansed” of the outside world when entering the rejuvenating garden.

LAA: How important is the site in informing your design concept and why?

KC: On some projects the site is a blank slate surrounded by boundary fences, while in others it’s a rural property with a strong environmental influence.

We have designed a number of gardens in Adelaide that take their cues from a historic turn-of-the-century sandstone villa at the front of the house and a contemporary addition at the rear. In these front gardens we have played with the idea of a ground plane of sandstone gravel punctuated with clipped hedge forms and/or trees. This simple and, we hope, elegant treatment is influenced by French Renaissance gardens and encourages a more spacious and meandering way of entering the garden.

LAA: Do you have a view on the role of art, craft, function and the prosaic, even mundane, in these gardens? And if so, how are these expressed?

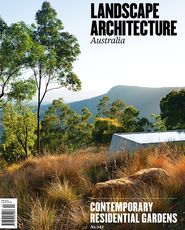

KC: Our gardens are often crafted with details that express a sense of the human hand and the care with which the garden has been created. Plants are fundamentally important to TCL gardens. We love to play with the form, colour, seasonal variety and texture of plants and initiate a conversation (or even tension) between the form of the garden and that of the dwelling. For example, at the Adelaide residence discussed in Landscape Architecture Australia (No 142), a mosaic-clad green wall provides a strong gestural arc that contrasts with the planting, which is designed to be slightly rambling, even chaotic.

LAA: Are there obvious pitfalls to carrying out residential garden work and do you have views as to why it is not discussed much in the Australian landscape architecture press?

KC: The only pitfall I find in designing gardens is that I get so involved with the clients and their gardens that sometimes it’s hard to make ends meet in terms of fees.

Maybe garden design is not discussed much because it is viewed as a lesser art, more aligned to garden design training, which is different from education in landscape architecture. There is, however, a lot that can be learnt from gardeners and garden designers, particularly and obviously in terms of planting and maintenance.

LAA: How many domestic gardens have you designed over the last ten to fifteen years (and types) and how important do you see this area of work in terms of your practice?

KC: TCL does not design a lot of gardens and we are selective about the ones that we embark on for the above reasons. There are approximately sixteen in Adelaide and Melbourne, with one in Japan. There are also the small domestic gardens in stage two of the Australian Garden and the Native Garden at the Botanic Gardens of Adelaide – projects where the brief was to inspire people with “take home” ideas about Australian plants for their domestic gardens.

LAA: What do you see as the future for landscape architects in this area of design in Australia?

KC: As more people move to cities the future could be the design of smaller, more urban gardens.

Source

Practice

Published online: 2 May 2016

Images:

Grant Hancock

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2014