Landscape Architecture Australia: What do you see as the particular values of the public garden?

Landscape architect Andrew Laidlaw.

Andrew Laidlaw: A lot of people these days aren’t able to experience wild nature so the garden becomes a platform to interact with nature. But public gardens are often designed with an adult language and that’s what we have to be careful of. If we put gardens together in a way that allows people, particularly children, to actually go in and use that space creatively, it’s such a fantastic aspect of what public gardens can do. Other values include green infrastructure, climate issues and mental health benefits. Green space is such an important aspect of people’s lives. Connecting to beauty is the other thing that public gardens do.

LAA: What particular contemporary stories or ideas of place, local nature and culture do you want to tell in your public gardens and how do you approach telling these?

AL: It’s a bit esoteric for me, that question.

LAA: [Laughs] Guilfoyle’s Volcano at the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne has a strong story behind it.

AL: It does. Guilfoyle was amazing and what he did there was almost a modernist or postmodern approach to garden design. He created a rustic garden folly in the middle of a public garden and that’s what Victorian gardens were all about, and he took it to great extremes. But the difference is that he drew his inspiration from nature and he laid that out in such a pared-back, powerful statement.

LAA: And did you follow a similar approach to Guilfoyle when you were redesigning it?

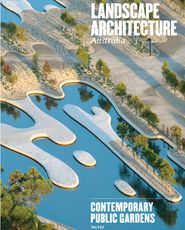

AL: I’m taking inspiration from Guilfoyle but I’m not trying to copy anything he did. I love the idea that it’s sitting there as a volcano and has that historic connection to Melbourne and to the Victorian landscape, but my interest was in using that theme to make a garden that is relevant and accessible. People weren’t allowed up there originally, it was something just to be looked at from afar. Whereas we wanted to get people in there, to understand what this landscape is doing. The other thing about the volcano is where it fits in the water management of the whole site. The volcano was the first stage of a three-stage project, bringing an extra seventy megalitres of stormwater into the lake system, treating it, pumping it and reticulating it through the volcano. You can learn all this at the top, where we created a series of viewing platforms. Visitors can then get up close to the floating islands, which are actually water filters. So the volcano is a landscape installation but it also has a role in the water management of the wider gardens. When the volcano was first designed in 1876, one of the things that got Guilfoyle the job was that he was going to build a reservoir so he could water the gardens and the gardens could expand. It was a very adventurous plan in its day. So the fact that the volcano has resurrected itself but is still all about water gives it a wonderful anchor for me.

Guilfoyle’s Volcano at the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne.

Image: Katie O’Brien

Plant selection was a major component to this project. I love planting and spend a lot of time thinking about planting design. And I think, sadly, that it’s largely missing from contemporary landscape architecture practice. I don’t mean there aren’t individuals doing it, but by and large it’s been going backwards. Guilfoyle used some very bold planting and we took clues from that. We read in the guidebooks that he’d said you could see the mess of mesembryanthemums, which are the little succulents, from Government House and we had a pictorial painting that showed lots of bold succulent material. So they were the two indications that we should use bold planting and succulents. Other factors that directed the planting theme were the adjacent arid collection and my interest in using arid and succulent plants in strong design combinations with many Australian arid plants. These plants have traditionally been used very poorly in gardens so providing strong design with them hopefully appeals to people, who may then choose to use them in their own gardens. These plants make a lot of sense in today’s changing climate. They require little water and can tolerate extreme weather patterns.

AL: The other major project I’ve done here in the Botanic Gardens is of course the Children’s Garden. I visited a lot of gardens in America and it was just like walking into Disneyland. I realized that it didn’t matter how much money you had. What we were really trying to do was create a place for children to connect to plants in their play. We wanted to inspire them, so that playing in amongst plants would become precious to them and build their understanding in a subconscious way.

LAA: Do you reference the creative or scientific works of others in your design work and, if so, who, what and how?

AL: I’m a huge fan of Roberto Burle Marx. I find him, Martha Schwartz and James van Sweden very inspiring. I was also impressed by the work of Mark McWha at the Dyeworks. And of course there’s Taylor Cullity Lethlean; they do amazing work.

LAA: Do you see the process of public garden-making as an artistic (or creative) practice and why?

AL: I do see garden-making as a creative process and love it for that, as a form of artistic expression.

LAA: What characteristics differentiate public garden-making from private in your view?

AL:I enjoy private gardens but I get much less satisfaction out of private design than I do public design. You feel as if you’re working for the public good, for the greater good of people. It’s also more challenging in private gardens because of detailing and client demands. There’s a lack of understanding of professionalism; they rip into your private time like you wouldn’t believe and I find it difficult. But again, I’m so interested in bringing gardens to connect plants with people that I suppose that’s my interest in doing private gardens.

LAA: Do you think there are major ideas or approaches that distinguish contemporary public garden-making from historic (particularly botanic) gardens and, if so, what are the distinguishing factors?

AL: People are demanding a lot more from their public spaces than they ever used to. And I think that’s because landscape architects have delivered fantastic contemporary public spaces all around the world – look at the High Line in New York, for example. We’re using space differently in Melbourne now, which is exciting, and our gardens and our landscapes have to reflect that. They become meeting places for people, not just to be admired from a distance, as perhaps once was the case.

LAA: How many public garden projects have you designed and what are these?

AL: I’m involved in a number of public garden projects and love the opportunity to connect to the public. Before the Children’s Garden and the volcano, a major project we did here at the Botanic Gardens in Melbourne was the Long Island indigenous garden, and then there’s been the Perennial Border and the Rose Species Garden. And we’ve done six or seven other botanic gardens, including Kyneton Botanic Gardens, Benalla Botanic Gardens, Hamilton Botanic Gardens and Ballarat Botanical Gardens. There’s a contemporary movement within those communities and they’re demanding more from their public spaces. It’s very exciting.

LAA: What are the challenges that characterize public garden projects?

AL: Budgets. In a word … [Laughs].