The Ian Potter Sculpture Court, nestled in the arc of the redesigned and refurbished Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) in Melbourne’s Caulfield, is both sculpture garden and part of the public realm of the campus. Completed several years ago by Kerstin Thompson Architects, Simon Ellis Landscape Architects and Fiona Harrisson, the courtyard received an urban design award from the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects in 2011. Now, the courtyard has settled and the plantings matured, which makes this an interesting moment to revisit the design as well as the collaborative partnership that produced it.

When briefed to review the MUMA forecourt, it was the nature of the collaboration that particularly interested me, engaged as I am in a working relationship that is in turn productive and difficult, challenging and immensely satisfying. In a professional realm where multidisciplinary teams are the norm and collaboration an everyday occurrence, real collaboration is also surprisingly rare.

I don’t refer here to the cooperation between the different professions necessary to such a public realm project as this. Nor do I mean the combined output of the team designing, documenting, administering. Rather, I am referring to the sort of collaboration that is synergistic, where complementary skills are no more important than the ability to work together for the good of the project; the sort of collaboration where individual ideas are subject to collective scrutiny and transformation, and where the lead consultant is able and willing to step into the process on an equal footing.

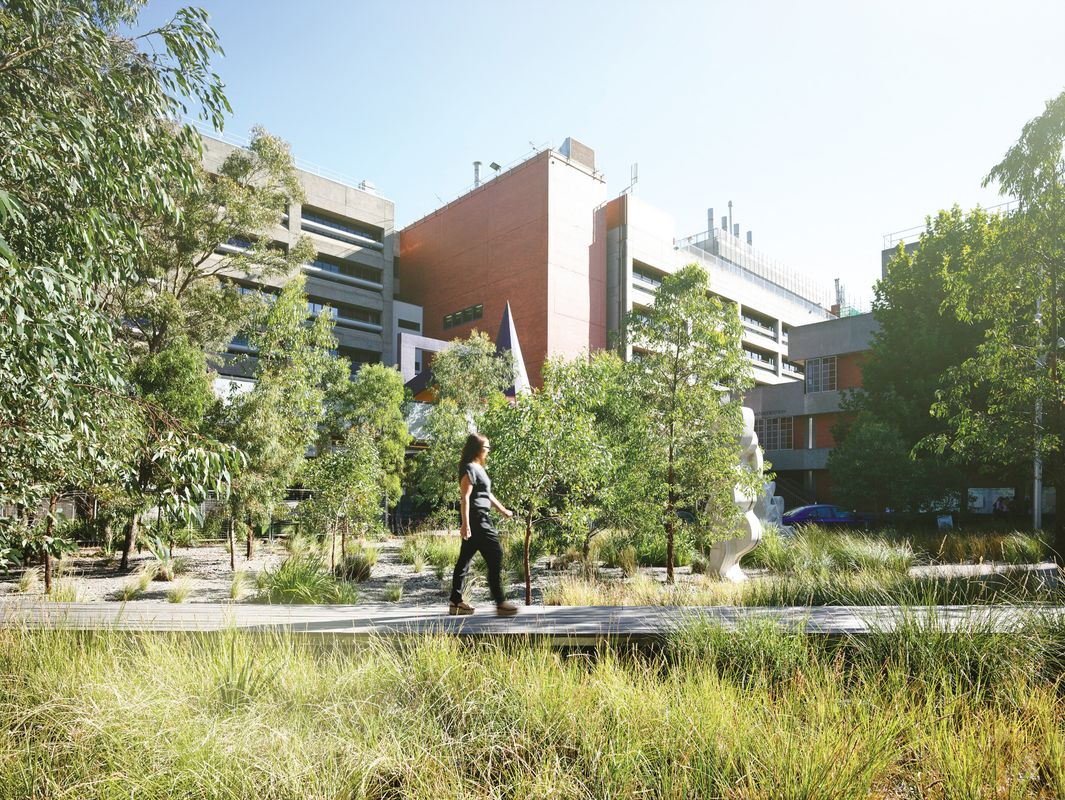

A sequence of timber platforms functions as boardwalks, seating and plinths.

Image: Derek Swalwell

This project demonstrates all these qualities. In conversation with Thompson, Ellis and Harrisson, it quickly becomes apparent that this is a working relationship grounded in mutual respect and generosity. While Thompson was instrumental in bringing the trio together, it is clear that any early, inevitable preconceptions of the courtyard’s potential were set aside to allow for the possibility of a stronger outcome.

Surprisingly, the building and forecourt were set as individual projects. The gallery is the result of a design competition, while the courtyard – then a carpark – was to be considered separately. In a campus context, the public realm plays a strong unifying role. Each space must work in concert with every other, including pedestrian connections, to provide a workable suite of spaces for its particular population. And in today’s education market, branding is always a central consideration. Accordingly, the public realm of Monash University’s Caulfield campus has been undergoing a revision, which includes removing vehicular traffic in favour of student-centred spaces.

However, this particular context, the form of the space, its connection to the gallery and the way in which it is bounded by the backs of buildings, all argued strongly for a different treatment. Just as the gallery is both a campus building and a community cultural asset, so too the forecourt must be of the campus yet distinct from it.

And so the carpark has become the forecourt, reorienting the gallery and providing both an external exhibition space and a momentary pause in campus life. In relation to MUMA, the courtyard provides a counterpoint to the internal gallery spaces and the artworks exhibited there. The views to the exterior space are both orienting and anchoring, making bodily sense of the interior geometry. The deep canopy underscores the reorientation of the building toward the courtyard. It allows the ubiquitous cafe to be unobtrusive, and separates the seating from the garden while providing a vantage point for viewing works exhibited inside and out.

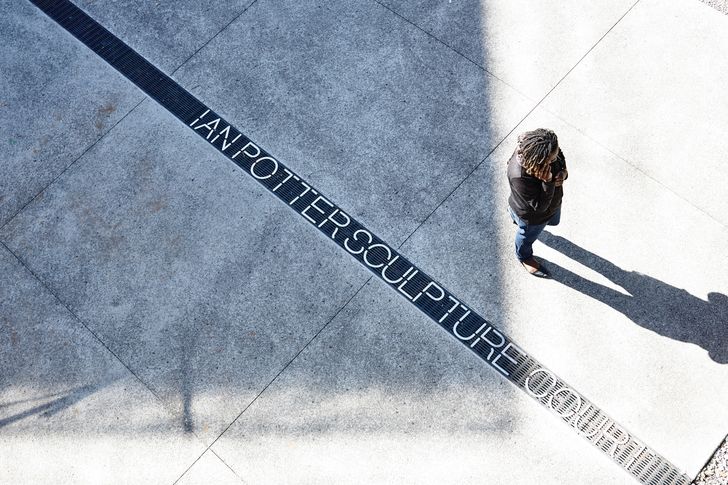

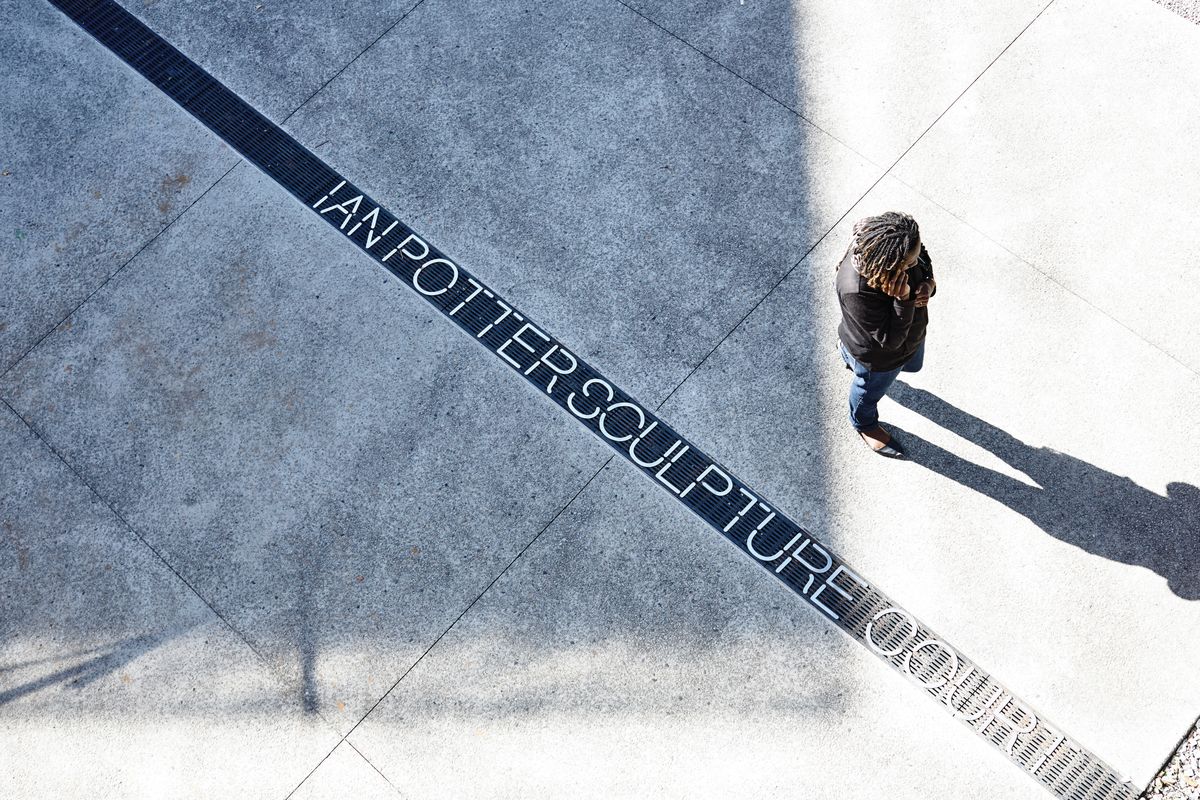

A plane of concrete pavers provides a generous space for gathering and holding events for the adjacent Monash University of Modern Art.

Image: Derek Swalwell

The courtyard houses a changing body of pieces, many commissioned by the museum for the space. These can be accommodated on the concrete plates or within the forest. The current pieces, Sanné Mestrom’s Weeping Women, work well within this space. Yet they also reveal something of the dilemma of sculpture gardens, where the space may be a setting for the artwork, or the artworks designed elements of the space. Mestrom’s three monumental concrete forms fit readily into a garden setting, even doubling as fountains, their placement evoking the seemingly interminable conversation of essentialism, the feminine and nature.

This design sets in place a background dialogue – one where place and the particular, the global art market, the qualities of contemplation and repose, precede the art created for it. The combination of spatial elements, the planting choices, the volumes that are in place and those that will develop over time all provide potential for engagement with changing artworks.

Benches offer places to study, rest or contemplate.

Image: Derek Swalwell

Along with the layers of dialogue is a layering of space. The ground plane of plates, rain gardens and understorey planting, the sequence of platforms as boardwalks, seating and plinths, and the maturing canopy of trees, together provide a dimensionality often lacking in urban spaces of this scale. This is emphasized by the gallery canopy and the upper walkways of adjacent buildings, which provide views into the courtyard and (eventually) through the trees.

New plantings of Eucalyptus tricarpa and Eucalyptus melliodora extend an existing coppice of the same species to create a “forest,” while Acacia implexa adds depth to the developing tree canopy. Rain gardens manage run-off and direct water flow to the forest, with the planting extending beyond and mixing with a range of other understorey plants. Sparseness in some areas signals a need for more active maintenance and follow-up replanting. Even at this stage the forest makes a neat visual link to mature groups of trees further into the campus, creating the perception of connection to what are probably isolated remnants of much earlier plans.

Ultimately, the MUMA forecourt carries with it a stillness and calm that seem to say as much about the design as they do about the integrity of the process and people who produced it. There is a sense of quietness here, which could be read as emptiness or restraint, or simply clarity of purpose. Collaboration is often of necessity, a noisy, untidy and sometimes fractious process of grappling with potential and possibility. That the Ian Potter Sculpture Court fits so comfortably into its physical and cultural context is immensely pleasing. That the integral qualities of this design suggest integrity of process can only be admired.

Credits

- Project

- Ian Potter Sculpture Court

- Practice

- Kerstin Thompson Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Practice

- Simon Ellis Landscape Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Practice

-

Fiona Harrisson (RMIT University)

- Consultants

-

Civil engineer

John Mullen & Partners

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 6 months

Construction 5 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens

- Client

-

Client name

Monash University

Source

Review

Published online: 7 Oct 2016

Words:

Kate Gamble

Images:

Courtesy of the design team,

Derek Swalwell

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2016