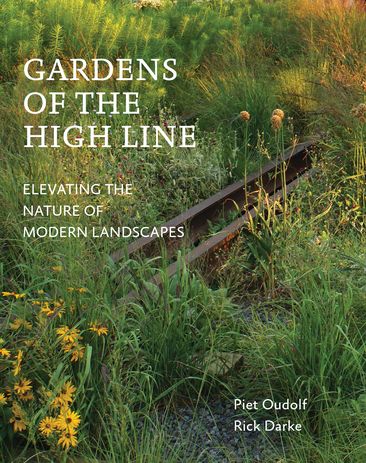

Piet Oudolf and Rick Darke, Gardens of the High Line: Elevating the Nature of Modern Landscapes (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 2017).

Image: courtesy Timber Press

I’m in my garden in the warmth of the winter sun, listening to the chatter of birds and the buzz of rosemary shrouded in bees. I’m reading Gardens of the High Line, drawn in by the sumptuous photography that seeks to convey as much about the High Line’s meaning as its beauty. Rick Darke is a landscape designer, lecturer and photographer who blends art, ecology and cultural geography. He has been photographing the project since 2002, capturing these immersive, intimate and tactile landscapes through hundreds of evocative photographs.

Founded in 1999 by Robert Hammond and Joshua David, and designed by James Corner Field Operations, Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Piet Oudolf, the High Line transforms an elevated railway into extraordinary public space in Manhattan’s West Side. The park is owned by the City of New York and maintained by the Friends of the High Line in partnership with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Like Seville’s Metropol Parasol, the High Line is a horizontal La Tour Eiffel, with visitor numbers exceeding those for the Statue of Liberty. More than seven million people annually traverse the High Line’s 2.3 kilometres through several neighbourhoods. Like the enduring Italian tradition of la passeggiata, “the High Line has helped people to rediscover the art of promenading” (Lisa Switkin, quoted in Gardens of the High Line, page 133). Unlike the nineteenth-century antidote Central Park, the High Line is a twenty-first-century “unprecedented urban landscape” that is as much about journey as it is destination, an “immersion in the city not an escape from it.”

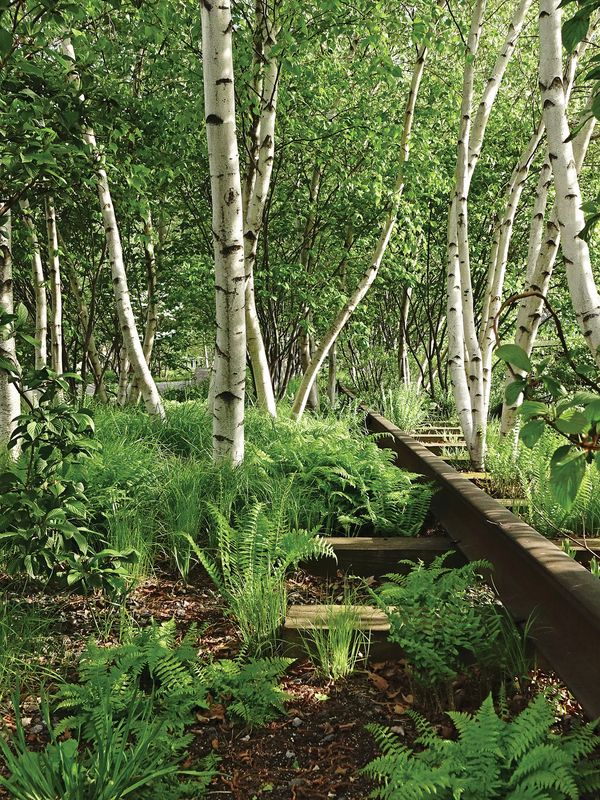

Images of detailed planting design along the High Line.

Image: Piet Oudolf

Piet Oudolf was responsible for the detailed planting designs. For Oudolf, “garden design is not just about plants, it is about emotion, atmosphere, a sense of contemplation”; plants are “living characters” in his designs. His desire is to move people, to play on the senses. The strength of this record relies as much on evocative imagery as on layers of complexity. It continually emphasizes the value of observing dynamic living processes: perfection in imperfection; a landscape in transition; “irresistible tensions” and contradictions between native and exotic; the weight of the steel work and the delicacy and ephemerality of the planting.

Images of detailed planting design along the High Line.

Image: Rick Darke

The book is organized in the order that you are most likely to experience the High Line, from Gansevoort Street at the south and moving toward the north, offering a curated selection of spectacular, enchanting and unpredictable garden displays, “small moments” and “little happenings.” One thing conspicuously absent, in comparison to Oudolf’s more recent books, is planting plans, but the compositions and plant combinations are evident through the detailed photography and annotations. A counterpoint to the rich photography is the celebratory nature of the language used to describe experience: a “choreography [of] transitions,” “energised journeys,” the “cadence” of “artful compositions,” and “mesmerising,” “revelatory” and “lilting” landscapes.

The Lurie Garden in Chicago’s Millennium Park was Oudolf’s first matrix planting; the High Line became an advanced matrix-based design at a grand scale. In 2004, when the design of the High Line gardens began, there were 161 identified plant species – eighty-two indigenous and seventy-nine introduced. By late 2016 there were four hundred different species. Understanding the High Line as a series of gardens and, better still, a matrix of ecologies gives the authors licence to talk of complexity and cultivation.

Due to their elevated nature, the High Line gardens must endure tough conditions, freezing more quickly and heating up more rapidly than other New York gardens.

Image: Rick Darke

The book describes the role of plants beyond appearance; as weed suppressants, for the conservation of moisture, for their relationship to context, and to provide levels of comfort and exposure. There are descriptions of the constraints of this spectacular podium landscape, with an underlying structure that “freezes more quickly and heats up more rapidly,” and of the horticultural difficulty of the spaces, from heat reflection to shallow planting depths, limited maintenance access, fertility, drainage and hydrology. The High Line is an environment free of herbicides and insecticides and the book describes the multitude of birds and insects that call it home. Like all gardens, the High Line is in a state of “constant experimentation and refinement,” but where the specific contextual constraints mean it is easier to “adapt plants to place rather than adapt place to plants.”

Gardens of the High Line is unashamedly about elevating the value of modern landscapes. While James Corner perhaps rightly asserts that the High Line is irreproducible because of the uniqueness of its context, the authors attest that the “design ethos … the patterning of plantings, enlightened stewardship, [are] highly reproducible and worthy of emulation.” For Hammond, the High Line is an “optimistic vision of people and place in changing times,” where “individual dreams [have led] to civic accomplishment.” But “the complexity and diversity of the High Line’s landscape is an uncommon experience in the realm of modern parks and public gardens.”

Piet Oudolf and Rick Darke, Gardens of the High Line: Elevating the Nature of Modern Landscapes (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 2017).

Source

Review

Published online: 9 Apr 2018

Words:

Claire Martin

Images:

Piet Oudolf,

Rick Darke

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, November 2017