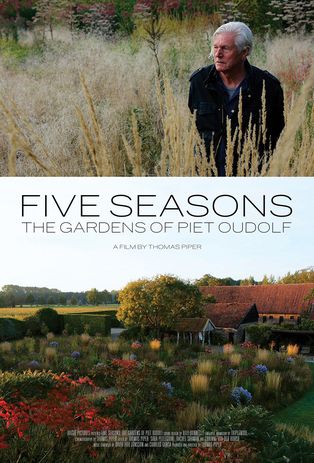

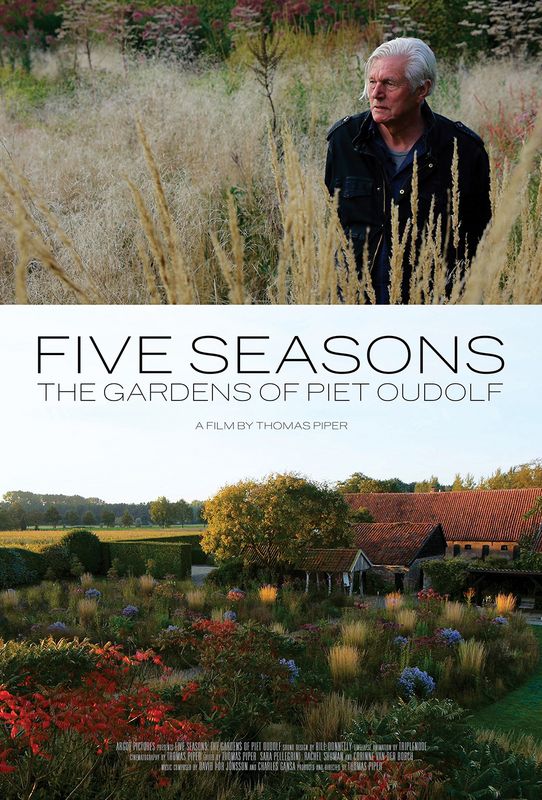

The 2017 documentary Five Seasons: The Gardens of Piet Oudolf by filmmaker Thomas Piper (co-director of Diller Scofidio and Renfro: Reimagining Lincoln Center and the High Line) is both opulent and modest. The documentary features interviews with landscape luminaries and benefactors including British garden designer Noel Kingsbury, James Corner and Lisa Switkin of Field Operations, landscape photographer Rick Darke and two of Swiss gallery Hauser and Wirth’s founders, Iwan and Manuela Wirth.

There is a poignancy to this film. Its slowness, observation and immersion are in stark contrast to a world obsessed with speed, instant gratification, planned obsolescence and digitally mediated experience. It is a movie with sumptuous colours and attention to detail – a first-person account of a man’s passion and purpose that conveys his generosity of spirit, sense of humour, humility and confidence. In this film, with equal parts catharsis and exegesis, time is a protagonist.

The film starts with Piet Oudolf at his desk, the scratch of his pen, childhood reminiscences, time-lapse footage of Oudolf’s wife Anja (“the big force behind [him]”) and their private garden and home in the Netherlands, Hummelo. It’s a cyclical narrative from autumn to autumn that charts the designer’s success across North America and Europe, from Battery Park, the Lurie Garden and the High Line to Hauser and Wirth’s Durslade Farm in the UK.

There’s a fondness and familiarity to the telling of Oudolf’s story – how he “met plants,” the fact that there was “something he needed and he found it.” It is a story less often told, one of process and complexity filtered through an atmosphere of fragility.

Five Seasons is a simple, elegant film that conveys Oudolf’s passion for plants and the importance of finding something you love and of making the most of the time we all have. There are a number of references to his own mortality and age: “I won’t come back, [but] they [the perennial plantings] will.” When asked if his work is political, Oudolf says, “Will [my work] save the world? I don’t know, but it saves me.”

Oudolf draws our attention to the power of plants and what they can do. We’re invited into the landscape to live, love and laugh – to “load up with beauty to put into [our] work, like loading up your batteries.” He deliberately moved away from decorative planting to focus on ambience, seasonality and spontaneity – on what plants do, rather than what they look like. Rick Darke – designer, photographer and a long-time collaborator of Oudolf’s – describes how the Dutch designer’s work “teaches people to see things they were unable to see.”

At the start of the film, Oudolf’s local shopkeeper asks if he is being followed by the camera crew, to which he responds, “No, I am leading [them].” And Oudolf has led, but dismisses references to the Dutch or New Perennial Movement. He designs what he likes. “If I like it, everyone will like it.” We are taken on a journey through his process, through trusted planting palettes and applications of hierarchy and mathematics. We see how he moves beyond the plan and puts himself on the ground at eye level.

It was as a child that Oudolf learned to observe and there are several scenes in which he is shown photographing his work, where he is the subject of our gaze and the landscape the subject of his. “[He] put[s] plants on stage and let[s] them perform.” Looking out over the Lurie Garden in Chicago, he recalls that “Fifteen years ago it was a parking deck … [it was my] first attempt to do a purely natural looking planting design [that] I couldn’t control, only conduct.” That marked the start of “new ideas” – “Lurie inspired the whole narrative of the High Line.”

Piper has directed a beautifully paced film that balances highly evocative scenes with thoughtful reflection. There is a richness to the cinematography that does justice to Oudolf’s compositions. The film’s aesthetic is as distinctive as the swathes of plants he leads us through; busying bees, drifting seeds, vibrating colours and textures fill the screen.

Standing in front of his “masterpiece” at Durslade Farm, Oudolf is described as “one of the great magicians.” But what this film perhaps best describes is his virtuosity – how he plans wildness. There is a universality to this film that will resonate whether you have experienced Oudolf’s landscapes directly, through books or not at all, because landscapes are our most primordial memories. Comforted by Oudolf’s thought and care, it was hard not to leave the screening with a sense that time had slowed.

Source

Review

Published online: 3 Jun 2019

Words:

Claire Martin

Images:

courtesy ACMI

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2019