Dyeworks Park, in Melbourne’s inner-city suburb of South Yarra, emerged from a timely combination of opportunities: inner-suburban post-industrial rejuvenation, a dynamic social context and a good budget from a supportive local council with federal government funding. It might easily have been a well-planted space of superior materials, but the outcome achieved much more than this.

The design’s unusually bold geometries and extent of colourful hardscaping, along with integrated custom furniture and play elements, set it immediately apart from any local park of similar scale – possibly of any scale in Australia at the time. The 1992 Barcelona Summer Olympics had excited landscape architects around the world with its range of innovative urban projects that were part of an investment in reimagining the city itself. Could this park do something similar?

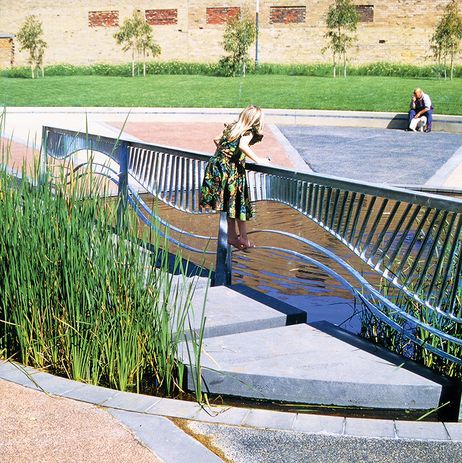

Radial bands of coloured concrete paving framing a central pond reference the fans of dye colour swatches used by the area’s former dye factories.

The park was designed in 1993 by Mark McWha and Associates, with McWha leading a design team that included Perry Lethlean (TCL), who produced the much-circulated, simple yet powerful hand-drawn plan; Nadia Gill; and Catherine Rush (Rush Wright Associates). The project is popularly thought to be the first cover of Landscape Architecture Australia magazine without a historic or bush garden. McWha’s young daughter featured in an image of the original pond, leaning over the water-wave steel railing from sawn bluestone stepping stones, set within bands of coloured concrete paving.

Dyeworks Park on the cover of the August 1994 issue of Landscape Architecture Australia.

The design for Dyeworks Park began with a limited invitation to three practices for submissions to develop sketch designs. The dye factory buildings had been removed not long before. Residents told stories of dye flowing in the gutters and coloured clouds of steam issuing from chimneys. This history of the site and the brief to provide for local family use shaped the winning proposal.

The main geometric gesture of the site design references a fan of dye colour swatches. The radial bands of different concrete and aggregate, along with the arced bowl of tilted lawn, still form a strong sense of focused space around the now-filled central “pond.” Custom steel grating across the stream and the central pond balustrade were fabricated locally. The retaining wall for the south-west lawn is just high enough to hide cars nosing in behind it. The boundary arc of car parking required by council was challenged by McWha who managed to reduce the number of spaces.

The most notable material feature of the park is a bold and varied use of basalt. Huge sectioned basalt boulders incorporate naturally weathered and rustic faces. They line the southern park edge, with several originally serving as fonts feeding a winding stream lined with quartz. A row of more conventional square-sawn, chamfered and chain-linked bollards protects the east. Bluestone also features as an unusual play material in the form of a “wombat” boulder studded with steel decoration, and a witchetty grub rock line with a “collar” of stainless steel handles. A U-shaped blue-pole larvae has a sliced stone head and inserted stone eye. While Dyeworks’ use of basalt didn’t predate the City of Melbourne’s first move in the seventies toward a bluestone palette, the stone had rarely been used outside the city previously. This rich material mix photographed well and made a powerful early impression on visitors.

Radial bands of coloured concrete paving framing a central pond reference the fans of dye colour swatches used by the area’s former dye factories.

Tree planting was dominated by two species: a broad double arc of lemon-scented gum (Corymbia citriodora) and a tight grid of Manchurian pear (Pyrus ussuriensis).

The pear trees were McWha’s second choice for the bosque. The first were river she-oaks, probably, he suggests, because of seeing them on the Molonglo River, with their wonderful carpet of needles. It might also be that the National Gallery of Australia Sculpture Garden, designed by Harry Howard in the late seventies, had an influence. Fujiko Nakaya’s fog sculpture is set amongst a grove of casuarina that would have been well-established by the nineties. Ultimately the species choice was an outcome of the council catering to a gentrifying demographic. McWha had intended for them to be pleached to emphasize the grid and overall geometry of the park design, but this didn’t eventuate.

Despite more recent concerns about messy bark or limb drop, there was little concern about proposing the double row of gums arching along the rear of the raised lawn and carpark beyond. These now make a noble white-trunked backdrop. Sadly, the few remnant native Pennisetum alopecuroides (swamp foxtail grass) beneath no longer luxuriously overflow the retaining wall. Locals have guerilla-planted other beds with succulents, white daisies, pink geranium and even some tomatoes, parsley, rocket and other vegetables.

The original stream was filled in after a few years because it attracted too many seagulls. For a while, the stream was a big attractor for younger children who would follow floating twigs and leaves along their journey to the pond. As both a key play element and a reference to the site history of dye running in the lanes and gutters, this was an unfortunate outcome for McWha.

The park’s original quartz-lined stream has been filled in.

Image: Jo Russell-Clarke

Asked what changes he might make today, McWha firstly suggests that the garden bed planting needs a refresh. Community consultation had not been part of the original pre-design work. However, it might be that re-engaging with local residents could direct a rethink on potential planting, resulting in other types of garden around the park’s boundaries.

Another simple improvement could be made by removing the existing shade sails. Three years after design completion, Prahran council decided to add a large shade canopy above an area of concrete paving (with no seats or much reason to loiter). McWha was engaged to design the structure, although he had argued that the trees would increasingly provide shade as they grew. Trees now do provide shade where people sit and congregate. Removing the distracting scale of the canopy would make the shape and organization of the park even clearer.

McWha suggests that although the stream, as designed, is too shallow and narrow to be transformed into a planted bio-swale, it could be meaningfully developed for that form. The pond could more easily be reinstated as a rain-garden, collecting site run-off and giving consideration to discouraging seagulls through denser planting.

The continuing high use of the park, even with low maintenance, speaks to the successful incorporation of so many functions into a small, highly legible space. Beyond car parking, the site fosters basketball and other ball play, barbecuing, picnicking, informal people-watching from the lawn, young children’s play within a close, shaded grove and even just enjoyably passing through to elsewhere.

A major upgrade is on the way for adjacent social housing with likely infill of their present lawn spaces. Dyeworks Park will become even more important as the backyard and play space for further families. Building on strong bones, a rejuvenation of Dyeworks Park can make it a local place of national quality for new generations to enjoy.

Source

Review

Published online: 25 Mar 2020

Words:

Jo Russell-Clarke

Images:

Jo Russell-Clarke

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2020